42b. Argentina: Antarctic museum of Ushuaia

Antarctic Museum of Ushuaia

The Antarctic Museum of Ushuaia, named Dr. José María Sobral to pay homage to the first Argentine sailor and scientist who wintered in the southern continent, lodges a large collection of ship models of Antarctic Expeditions, which is, according to the Lonely Planet guide“ … Perhaps the best collection of Antarctic ship models anywhere in the world is displayed in various parts of the museum. Among the dozens of examples are Amundsen’ Fram; Scott’s Discovery; Shackleton’s Endurance; De Gerlache’s Belgica; Charcot’s Le Français and Pourquoi-Pas; Nordenskjöld Antarctic; Argentina’s Uruguay (which recued Nordenskjöld in 1903 and also relieved Bruce in 1904); Argentina’s Bahía Paraíso (wrecked in Antarctica in 1989, causing a massive fuel spill); and the Argentine icebreaker Almirante Irízar (the actual ship often reprovisions in Ushuaia).

The Amundsen and Scott polar expeditions

Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen; 16 July 1872 – c. 18 June 1928, was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen; 16 July 1872 – c. 18 June 1928, was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Amundsen began his career as a polar explorer as first mate on Adrien de Gerlache’s Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897–1899. From 1903 to 1906, he led the first expedition to successfully traverse the Northwest Passage on the sloop Gjøa. In 1909, Amundsen began planning for a South Pole expedition. He left Norway in June 1910 on the ship Fram and reached Antarctica in January 1911. His party established a camp at the Bay of Whales and a series of supply depots on the Barrier (now known as the Ross Ice Shelf) before setting out for the pole in October. The party of five, led by Amundsen, became the first to reach the South Pole on 14 December 1911.

Following a failed attempt in 1918 to reach the North Pole by traversing the Northeast Passage on the ship Maud, Amundsen began planning for an aerial expedition instead. On 12 May 1926, Amundsen and 15 other men in the airship Norge became the first explorers verified to have reached the North Pole. Amundsen disappeared in June 1928 while flying on a rescue mission for the airship Italia in the Arctic. The search for his remains, which have not been found, was called off in September of that year.

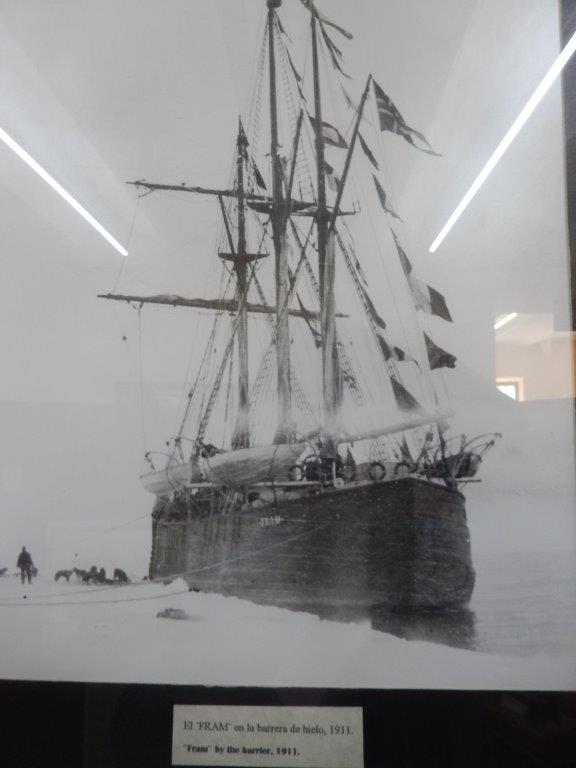

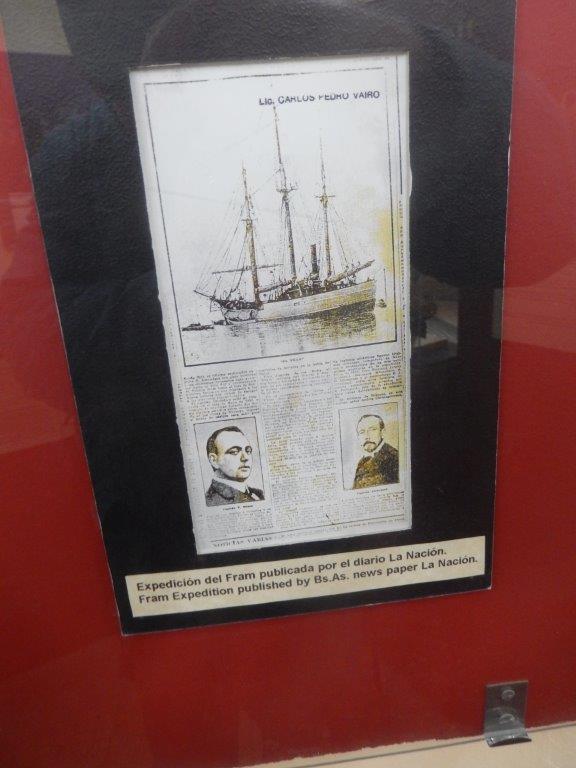

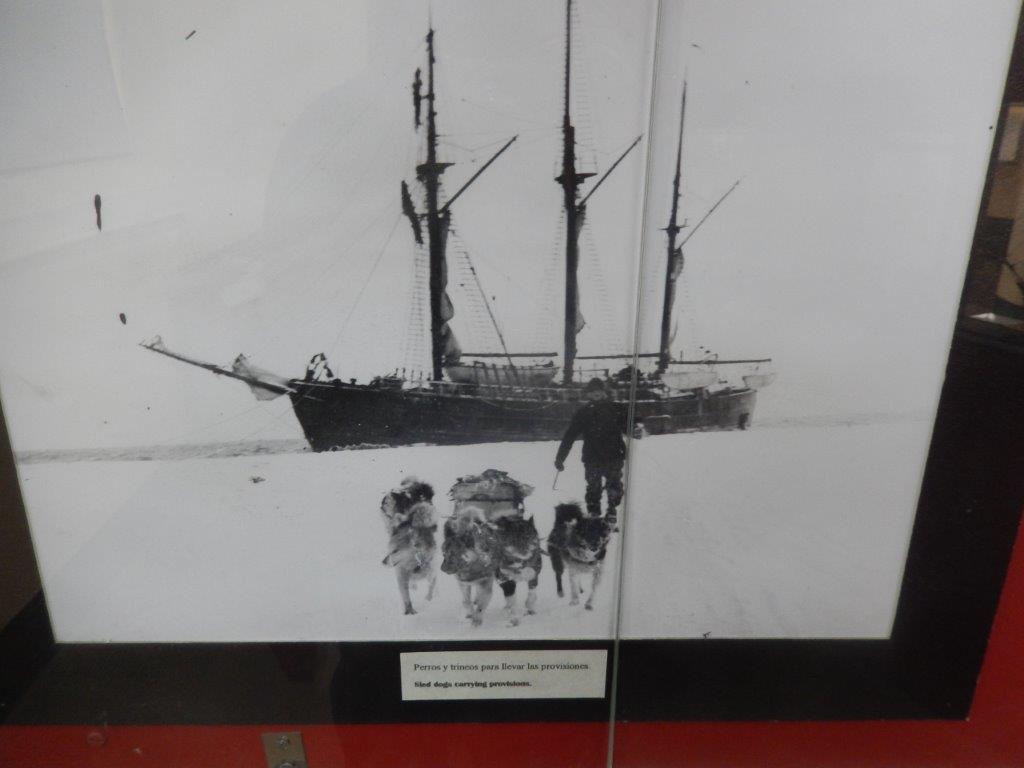

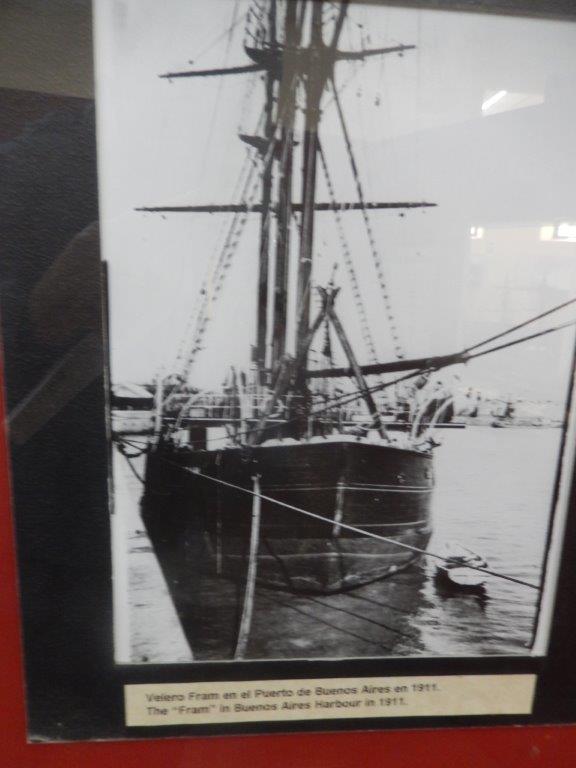

Beneath is a photo series of the Fram, the ship Amundsen used for his succesful Southpole expedition.

Using skis and dog sleds for transportation, Amundsen and his men created supply depots at 80°, 81° and 82° South on the Barrier, along a line directly south to the Pole. Amundsen also planned to kill most of his dogs on the way and use them as a source for fresh meat. As he went he butchered some of the dogs and fed them to the remaining dogs, as well as eating some himself. A small group, including Hjalmar Johansen, Kristian Prestrud and Jørgen Stubberud, set out on 8 September, but had to abandon their trek due to extreme temperatures. The painful retreat caused a quarrel within the group, and Amundsen sent Johansen and the other two men to explore King Edward VII Land.

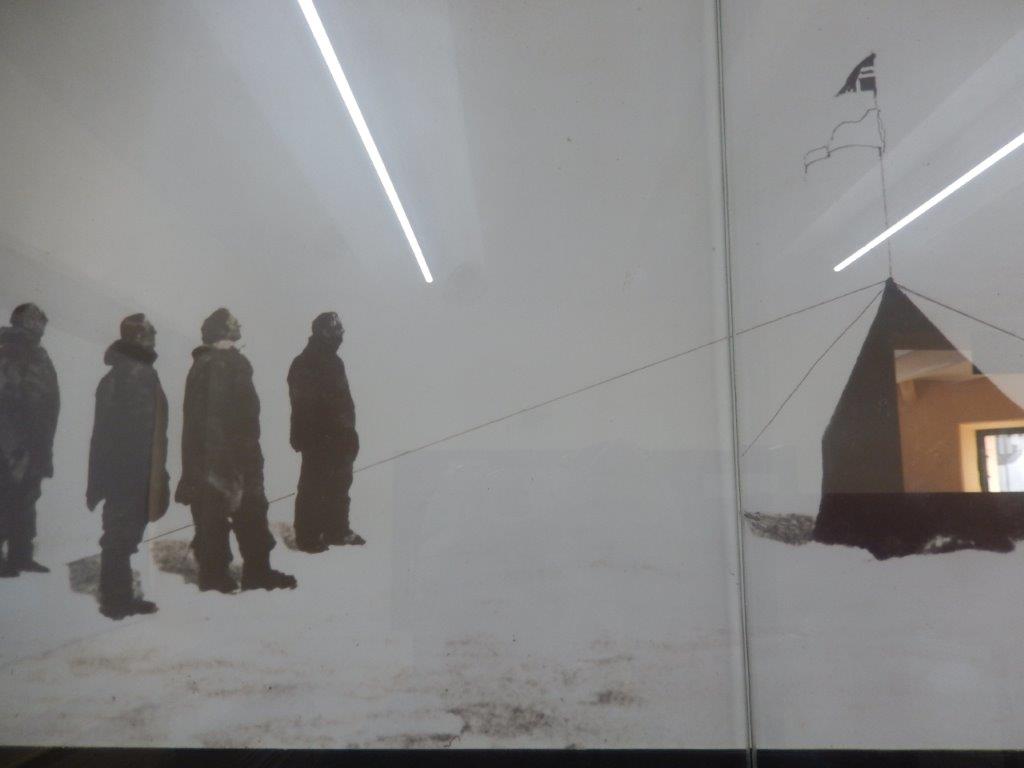

A second attempt, with a team of five made up of Olav Bjaaland, Helmer Hanssen, Sverre Hassel, Oscar Wisting and Amundsen, departed base camp on 19 October. They took four sledges and 52 dogs. Using a route along the previously unknown Axel Heiberg Glacier, they arrived at the edge of the Polar Plateau on 21 November after a four-day climb. The team and 16 dogs arrived at the pole on 14 December, a month before Scott’s group. Amundsen named their South Pole camp Polheim. Amundsen renamed the Antarctic Plateau as King Haakon VII’s Plateau. They left a small tent and letter stating their accomplishment, in case they did not return safely to Framheim.

The team arrived at Framheim on 25 January 1912, with 11 surviving dogs. They made their way off the continent and to Hobart, Australia, where Amundsen publicly announced his success on 7 March 1912. He telegraphed news to backers.

Amundsen’s expedition benefited from his careful preparation, good equipment, appropriate clothing, a simple primary task, an understanding of dogs and their handling, and the effective use of skis. In contrast to the misfortunes of Scott’s team, Amundsen’s trek proved relatively smooth and uneventful.

Scott

Even more impressive were these travel notebook fragments of Scott. When I was still very young I read this children’s book (I completely forgot its name or how it looked) about Scott’s journey to the southpole and back (well partly back) which to me read like a thriller. It enthousiasmed me for polar travels.

Beneath are some of the most heartbreaking notes he made..

Imagine having made this long exhausting expedition to the southpole, only to find that Amundsen has beaten you to it, just a couple of weeks earlier and then, utterly disappointed having to return through that white hell. Scott never made it back, but his notebook did…

I really felt very much drawn back into the book I read about Scott when seeing these notebook pages. I also was very much in doubt whether I would have been able to make such an honest drawing of Amundsen’s tent and the Norse flag above it.

The book I read back then was so much more vivid than I could ever hope writing, but I hope you do get the picture of someone’s mood after such an ordeal and it must have been of influence on Scott’s stamina when he returned to his ship and got into some real bad antarctic weather…

Captain Robert Falcon Scott CVO (6 June 1868 – c. 29 March 1912) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the Discovery expedition of 1901–04 and the Terra Nova expedition of 1910–13.

Captain Robert Falcon Scott CVO (6 June 1868 – c. 29 March 1912) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the Discovery expedition of 1901–04 and the Terra Nova expedition of 1910–13.

On the first expedition, he set a new southern record by marching to latitude 82°S and discovered the Antarctic Plateau, on which the South Pole is located. On the second venture, Scott led a party of five which reached the South Pole on 17 January 1912, less than five weeks after Amundsen’s South Pole expedition. A planned meeting with supporting dog teams from the base camp failed, despite Scott’s written instructions, and at a distance of 162 miles (261 km) from their base camp at Hut Point and approximately 12.5 miles (20.1 km) from the next depot, Scott and his companions died. When Scott and his party’s bodies were discovered, they had in their possession the first Antarctic fossils discovered. The fossils were determined to be from the Glossopteris tree and proved that Antarctica was once forested and joined to other continents.

Before his appointment to lead the Discovery expedition, Scott had a career as a Royal Navy officer. In 1899, he had a chance encounter with Sir Clements Markham, the president of the Royal Geographical Society, and learned of a planned Antarctic expedition, which he soon volunteered to lead. His name became inseparably associated with the Antarctic, the field of work to which he remained committed during the final 12 years of his life.

Following the news of his death, Scott became a celebrated hero, a status reflected by memorials erected across the UK. However, in the last decades of the 20th century, questions were raised about his competence and character. Commentators in the 21st century have regarded Scott more positively after assessing the temperature drop below −40 °C (−40 °F) in March 1912, and after re-discovering Scott’s written orders of October 1911, in which he had instructed the dog teams to meet and assist him on the return trip.

On the 2nd floor is an extensive exhibit of stamps and postcards from Antactica, Tierra del Fuego and Ushuaia, along with a “relax zone” and a gift shop. …”.

Located on the second floor of Pavilion IV of the former Prison of Ushuaia of Tierra del Fuego—, it has nineteen exhibit halls that enshrine the richest heritage of preserved historic and biological Antarctic materials. Tools used by the early polar expeditions, a reproduction of the shack used by Doctor Andersson mounted with original materials used by the three men who had to winter at Hope Bay (Bahía Esperanza) in 1903 recovered through archaeological techniques from the ruins of the shack mentioned above: artifacts of the Swedish expedition headed by Doctor Nordenskjöld (1901-1903), a name The Wandelgek remebred from his visit to Lago Nordenskjöld in Chile, whaling history; photos and books of the Belgian expedition by Adrien de Gerlache (1898-1899); a reproduction with the original elements from the old radio station of the scientific base Brown; accounts about Antarctic pioneers such as Gustavo Giró, Jorge E. Leal, who headed the first Argentine expedition to the South Pole, and Hernán Pujato, founder of the Instituto Antártico Argentino in 1951, models of the vessels of the Argentine Navy and the planes that took part in exploring the continent as from the early 20th century and from the first station for research on the high atmosphere that operated at Belgrano I Station as of 1954.

The exhibit also includes a fossils collection and taxidermy bird specimens.

Given the geographical features of the area, the Argentine Navy was the one that established permanent links with the presence of men in Antarctica.

One hundred years in the station on South Orkneys and the rescuing of the scientific expedition headed by Otto Nordenskjöld (1903 – corvette Uruguay) and, at the beginning of this century, the rescue of the clipper Adventure, a cruise with passengers (summer 2000), among others.