11. Argentina: Desert town of Esquel and the decline of the Old Patagonian Express

The desert town of…

Esquel

Esquel is a town in the northwest of Chubut Province in Argentine Patagonia. It is located in Futaleufú Department, of which it is the government seat. The town’s name derives from one of two Tehuelche words: one meaning “marsh” and the other meaning “land of burrs”, which refers to the many thorny plants including the pimpinella, and the other meaning herbaceous plants whose fruits, when ripe, turn into prickly burrs that stick to the animals’ skins and wool or people’s clothes as a way of propagation.

The founding of the town dates back to the arrival of Welsh immigrants in Chubut in 1865. The settlement was created on 25 February 1906, as an extension of the Colonia 16 de Octubre, that also contains the town of Trevelin.

The city, the main town of the area, is located by the Esquel Stream and surrounded by the mountains La Zeta, La Cruz, Cerro 21 and La Hoya. La Hoya is known as a ski resort with good quality snow right through the spring. The Los Alerces National Park is 50 km (31 mi) northwest of the city.

The streets of Esquel were gravel and dirt roads and the few cars driving through caused a dust cloud to stick around for quite a while. Occasionally a dandy dressed gaucho on horseback passed by, probably having visited one of the shops selling leatherwear like saddles or cowboy like hats.

The Wandelgek decided to quickly drop his luggage in his hotelroom, which was quite a nice room.

A clean bathroom with a shower, toilet, hair blower and even a bidet…

After having quickly dumped his luggage, The Wandelgek took a cab towards the Esquel railway station.

The Argentine Railway Network

The Argentine railway network consisted of a 47,000 km (29,204 mi) network at the end of the Second World War and was, in its time, one of the most extensive and prosperous in the world. However, with the increase in highway construction, there followed a sharp decline in railway profitability, leading to the break-up in 1993 of Ferrocarriles Argentinos (FA), the state railroad corporation. During the period following privatisation, private and provincial railway companies were created and resurrected some of the major passenger routes that FA once operated.

The growth and decline of the Argentine railways are tied heavily with the history of the country as a whole, reflecting its economic and political situation at numerous points in history, reaching its high point when Argentina ranked among the 10 richest economies in the world (measured in GDP per capita) during the country’s Belle Époque and subsequently deteriorating along with the hopes of the prosperity it came so close to achieving.

In the early years, the railway was emblematic of the vast waves of European Immigration into the country, with many coming to work on and operate the railways, such as the Italian-Argentine Alfonso Covassi, the country’s first engine driver, and also in the sense that the population boom experienced as a result of this immigration required means of transportation to meet growing demands. Much like in the American West, the railways also played a key role in the creation and expansion of new population centres and boomtowns in remote parts of the country.

During its existence there were several efforts (depending on which government or military junta was in power to either privatise or nationalise the railway network. In the end the often mob run transportation companies that also used to earn their money by road transport (the roads had gotten much better since the early days of the rail roads), stopped investments in the less profitable railway network, thus causing the rail roads to deteriorate and it soon had to be closed almost entirely.

The closing of much of the rail system also led to the emptying of many rural towns dependent on the railways, creating ghost towns and therefore to a dismantling of the development that had taken place there since the arrival of trains. Argentine agriculture found itself in the difficult position of shipping its goods less efficiently using road transport, which costs around 72% more than state-owned rail services.

Patagonia was of course the most difficult area for running a profitable railway, but there had been efforts for railway lines in Patagonia too.

Esquel Railway Station

An important tourist attraction is the narrow-gauge railway (with 750 mm (30 in) between the rails), known as La Trochita locally and in English as The Old Patagonian Express after the book The Old Patagonian Express by Paul Theroux.

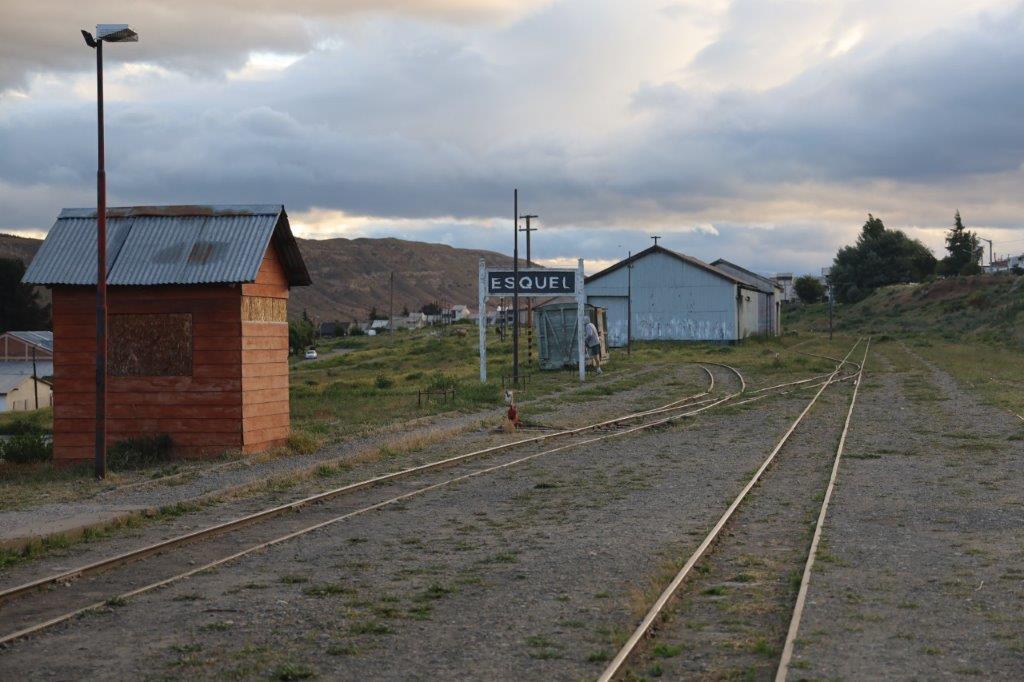

The sun was slowly setting as the last sunlight hit the surrounding mountains, The Wandelgek took his camera and a lot of time to create some specific images which still look really good, like the one above.

As soon as The Wandelgek entered the railway statiin area he was reminded of the opening scenes of “Once upon a time in the West, Sergio Leone’s masterpiece, where some thugs are killing time, waiting for the arrival of the notorious Man with harmonica. Although the station was clearly from a latter decennium, it still had that same vibe of not being of importance to anyone, of slow but sure decay and of dustiness. A place soon completely forgotten…

At 402 km (250 mi) in length, it is said to be the only narrow-gauge long-distance line in operation and the southernmost railway in the world. Railway meaning railway network, because The Wandelgek discovered an even southermoster (is that a word?🤣) railway, but more of that later in an upcoming blogpost.

The train station of Esquel seemed quite marooned when The Wandelgek visited it.

The first fifty oil-fired steam locomotives were made by Henschel & Son of Germany in 1922. Later twenty-five locomotives were bought from the Baldwin Locomotive Works of Philadelphia.

The train remains authentic and in operation thanks to the effort of the team of workers at Talleres Ferroviarios El Maiten, that make several parts by hand. Trains now run as a tourist excursion between Esquel and the small settlement of Nahuel Pan, located at the foot of the volcano of the same name, with other services all the way to El Maitén. Until 1993, the train ran all the way to the city of Ingeniero Jacobacci in Río Negro Province, from where trains ran to Viedma, Río Negro and from there to Buenos Aires, forming the General Roca railway.

The decline and demise of the Patagonian Express

La Trochita (official name: Viejo Expreso Patagónico), in English known as the Old Patagonian Express, is a 750 mm (2 ft 5+1⁄2 in) narrow gauge railway in Patagonia, Argentina using steam locomotives. The nickname La Trochita means literally “The little gauge” though it is sometimes translated as “The Little Narrow Gauge” in Spanish while “trocha estrecha”, “trocha angosta” in Argentina, is often used for a generic description of “narrow gauge.”

The Trochita railway is 402 km in length and runs through the foothills of the Andes between Esquel and El Maitén in Chubut Province and Ingeniero Jacobacci in Río Negro Province, originally it was part of Ferrocarriles Patagónicos, a network of railways in southern Argentina. Nowadays, with its original character largely unchanged, it operates as a heritage railway and was made internationally famous by the 1978 Paul Theroux book The Old Patagonian Express, which described it as the railway almost at the end of the world.Theroux had sought to ride trains as far as possible into southern Argentina but did not include in his adventures the several railroads which were further south than Esquel, presumably because they were not considered operational or with sufficient connection to larger lines.

The railway station of Esquel was the last one in the Chubut River valley. The southernmost station where backpackers could get before they had to use other means of transport to go on….

In 1908, the Government of Argentina planned a network of railways across Patagonia. Two main lines would join San Carlos de Bariloche in the central Andes with the sea ports of San Antonio Oeste on the Atlantic coast to the east, and Puerto Deseado on the coast to the south east. Branches were to be built to connect the mainline with Buenos Aires Lake (connecting at Las Heras) and Comodoro Rivadavia (connecting at Sarmiento). Colonia 16 de Octubre – the Esquel and Trevelin area – would be connected via a branch line to Ingeniero Jacobacci. The whole network would connect to Buenos Aires via San Antonio Oeste.

The project ran out of steam following ministerial changes and the start of World War I which affected the economy of Argentina and the input of technology and investment required from Europe. The northern main line from the coast reached Ingeniero Jacobacci in 1916. 282 km of the southern main line from Deseado to Las Heras, and the 197 km branch line from Comodoro Rivadavia to Sarmiento were laid, but never connected with each other or the northern network. After 1916, the only further work was the completion of the link from Jacobacci to Bariloche, finished in 1934.

The exception was the Esquel line. After the end of the First World War, narrow gauge track and facilities were plentiful and cheaper, given their extensive use at the front for supplies and troop movement. 600 mm (1 ft 11+5⁄8 in) ä Decauville railroads were used extensively in Buenos Aires Province in rural areas and to carry freight. For passenger services, locomotives for 750 mm (2 ft 5+1⁄2 in) track were readily available and it was decided to pursue this cheaper option. In 1921 it was agreed to lay down the Jacobacci-Esquel line, and also to connect it with the existing private 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in) gauge railway in the Chubut Valley from Dolavon to Puerto Madryn. This would be the Patagonian Light Railways Network.

Belgian coaches and freight wagons were ordered in 1922, plus fifty locomotives from Henschel & Sohn, a German company in Cassel (today spelt Kassel). Later 25 more locomotives were bought from the Baldwin Locomotive Works in Philadelphia, U.S.A.

The first part of the project was to lay a third rail inside the existing tracks at Jacobacci and the Chubut Valley so that they could be used by the narrow gauge vehicles. New tracks were laid to extend the Chubut Valley line from Trelew to Rawson at the coast and westwards to Las Plumas. After floods destroyed much of the line in 1931–1932, work began again in 1934 with new plans, with a 105 m-long bridge and a 110 m-long tunnel to be built. 1,000 labourers worked in the harsh Patagonian environment, many later settling.

Trains began to run on the completed parts of the line in 1935. In 1941 the line reached El Maiténp, where maintenance facilities were built. The first train to Esquel entered the city on May 25, 1945. After President Juan Perón’s nationalisation of the railway network in 1948, the Trochita became part of General Roca Railway.

Until 1950 the line was a freight-only service. The first passenger service launched in 1950 and connected Esquel with Buenos Aires (arriving at Constitución station), changing trains at Jacobacci. Passengers would occupy loose wooden benches around a stove which could be used for light cooking and above all to prepare mate and keep warm. The bends of the line in the Andean foothills and the slow speed of the network allowed passengers to walk alongside the train on certain sections along the 14-hour journey.

The service was much used for freight through the 1960s and 1970s, contributing to the development of the area, especially the construction of the dam on the Futaleufú River and the growth of El Maitén thanks to the locomotive maintenance operation.

Decline

Decline

In 1961, the line in the lower Chubut valley between Puerto Madryn and Las Plumas was closed, never having been connected with the Esquel or Bariloche lines. In the 1970s the two isolated lines to the south also shut down.

La Trochita also began to decline, due to the improvement of the road network and of trucks and buses, and the difficulties of maintaining a railway so far from the country’s capital and the global rail industry. However over the same period, Patagonia had been ‘discovered’ by tourists and La Trochita was something of a backpacker highlight. Theroux’s book brought it to wider attention and gave the railway a name – The Old Patagonian Express – which highlighted its timeless appeal both to Argentine nostalgics and tourists. In 1991, the railway was filmed for an episode of Nick Lera’s World Steam Classics.

Nevertheless, the line was not profitable. Given the communities it served, private investors were not interested in making necessary investment. In 1992, under the liberal economic practices of the central government, it was decided to close the line. However, there was a national and even an international outcry at the decision to close a line which had become emblematic of a bygone age and of that region. The two provincial governments came together to keep the line open.

The line is in possession of 22 steam locomotives, 11 Henschel and 11 Baldwin Mikado type locomotives, seven of which are currently operable, two Baldwin and three Henschel in the El Maitén – Esquel section, and 2 Baldwin locomotives in the Ingeniero Jacobacci section. The locomotives are oil fired and have been in continuous service since its introduction. There are no diesel engines in use anywhere on the line. The present rolling stock as the locomotives date from 1922, with the exception of the dining car and some first class carriages that were constructed in 1955.

The train no longer runs between Esquel and El Maitén; instead two special tourist services run (i) between Esquel and the settlement of Nahuel Pan and (ii) between El Maitén and Desvío Thomae.

The journey from Esquel to El Maitén took almost seven hours. There is a regular tourist service which offers a return trip to the first station and back which takes about an hour. As of 2010, tickets for the tourist services are ARS$150 round-trip, and a discount to $80 for residents of Argentina.

The maintenance of the original 1922 locomotives is increasingly difficult, due to the lack of parts and expertise, and the remoteness of his base in El Maitén. This can cause frequent delays or service shut-downs.

The Government of Argentina declared La Trochita as a National Historic Monument in 1999.

In 2003, “Friends of La Trochita Association” was created by members mainly from Esquel, El Maitén and Bariloche.

In May 2011, high winds ripped the roof off one car. The roof fell down in between two cars, derailed one which then caused the entire train to derail and roll over. No one was seriously injured and the locomotive and cars were all recovered by June 1, 2011.

After his visit to the Esquel railway station, The Wandelgek went into town to one of its central roads, where one of the old locomotives that is beyond repair is exhibited…

For The Wandelgek it had been Paul Theroux’s book: The old Patagonian Express: By train through the Americas, which instigated his visit to the Esquel Railway Station. The Old Patagonian Express (1979) is a written account of a journey taken by novelist Paul Theroux. Starting out from his home town in Massachusetts, via Boston and Chicago, Theroux travels by train across the North American plains to Laredo, Texas. He then crosses the border and takes a train south through Mexico to Veracruz where he meets a woman looking for her long-lost lover. He then takes the train south into Guatemala and then El Salvador where he goes to a soccer match and is amazed by the violence. He then flies to Costa Rica where he takes the train to Limón and Puntarenas. He ended his transit of Central America in Panama where he takes the short train ride across the isthmus. Theroux then proceeds to Colombia and then over the Andes and finally reaches the small town of Esquel in Patagonia. He endures harsh climates, including the extreme altitude of Peru and the Bolivian Plateau, meets the author Jorge Luis Borges in Buenos Aires and is reunited with long lost family in Ecuador.

For The Wandelgek it had been Paul Theroux’s book: The old Patagonian Express: By train through the Americas, which instigated his visit to the Esquel Railway Station. The Old Patagonian Express (1979) is a written account of a journey taken by novelist Paul Theroux. Starting out from his home town in Massachusetts, via Boston and Chicago, Theroux travels by train across the North American plains to Laredo, Texas. He then crosses the border and takes a train south through Mexico to Veracruz where he meets a woman looking for her long-lost lover. He then takes the train south into Guatemala and then El Salvador where he goes to a soccer match and is amazed by the violence. He then flies to Costa Rica where he takes the train to Limón and Puntarenas. He ended his transit of Central America in Panama where he takes the short train ride across the isthmus. Theroux then proceeds to Colombia and then over the Andes and finally reaches the small town of Esquel in Patagonia. He endures harsh climates, including the extreme altitude of Peru and the Bolivian Plateau, meets the author Jorge Luis Borges in Buenos Aires and is reunited with long lost family in Ecuador.

The Wandelgek read this book a few years after he read Riding the iron rooster, about Theroux’s railway adventure in China.

Then it was time for dinner and The Wandelgek visited a Parilla (Grill and BBQ Restaurant) in down town Esquel…

Then it was time for dinner and The Wandelgek visited a Parilla (Grill and BBQ Restaurant) in down town Esquel…

… to eat some typical Agentinian meat dish.The kitchen and grillroom were visible from the restaurant and so was the meat that would end on the dish.

Argentina is the number 1 country in the world when it comes to meat consumption. Parilla’s are the most common restaurant type in Argentina. This one had an open kitchen behind large glass windows. As a guest you could watch the grilling or barbecueing of the meat…

Argentina is the number 1 country in the world when it comes to meat consumption. Parilla’s are the most common restaurant type in Argentina. This one had an open kitchen behind large glass windows. As a guest you could watch the grilling or barbecueing of the meat…

A mix of meat (pig, calf, veal, chicken and a bowl of vegetables was served…

Vegetarianism or veganism are maybe tucked away in sparse restaurants in large cities, but they are no common pressence, certainly not in the smaller towns and villages. The Wandelgek also tried a local Esquel beer. They have a Golden Ale, a Red Ale (which is the one The Wandelgek ordered) and a Stout.

After a great dinner, The Wandelgek visited a cervezeria near his hotel for a few more drinks before returning to his hotel room. This had been a wonderful day in the dry, unyielding wilderness of the Patagonian Desert, but now The Wandelgek had seen the white crested summits of the nearby Andes mountains, he was very anxious to leave the desert and move into those mountains.

After a great dinner, The Wandelgek visited a cervezeria near his hotel for a few more drinks before returning to his hotel room. This had been a wonderful day in the dry, unyielding wilderness of the Patagonian Desert, but now The Wandelgek had seen the white crested summits of the nearby Andes mountains, he was very anxious to leave the desert and move into those mountains.