Raise the Red Lantern: Cuandixia, a Chinese village frozen in time

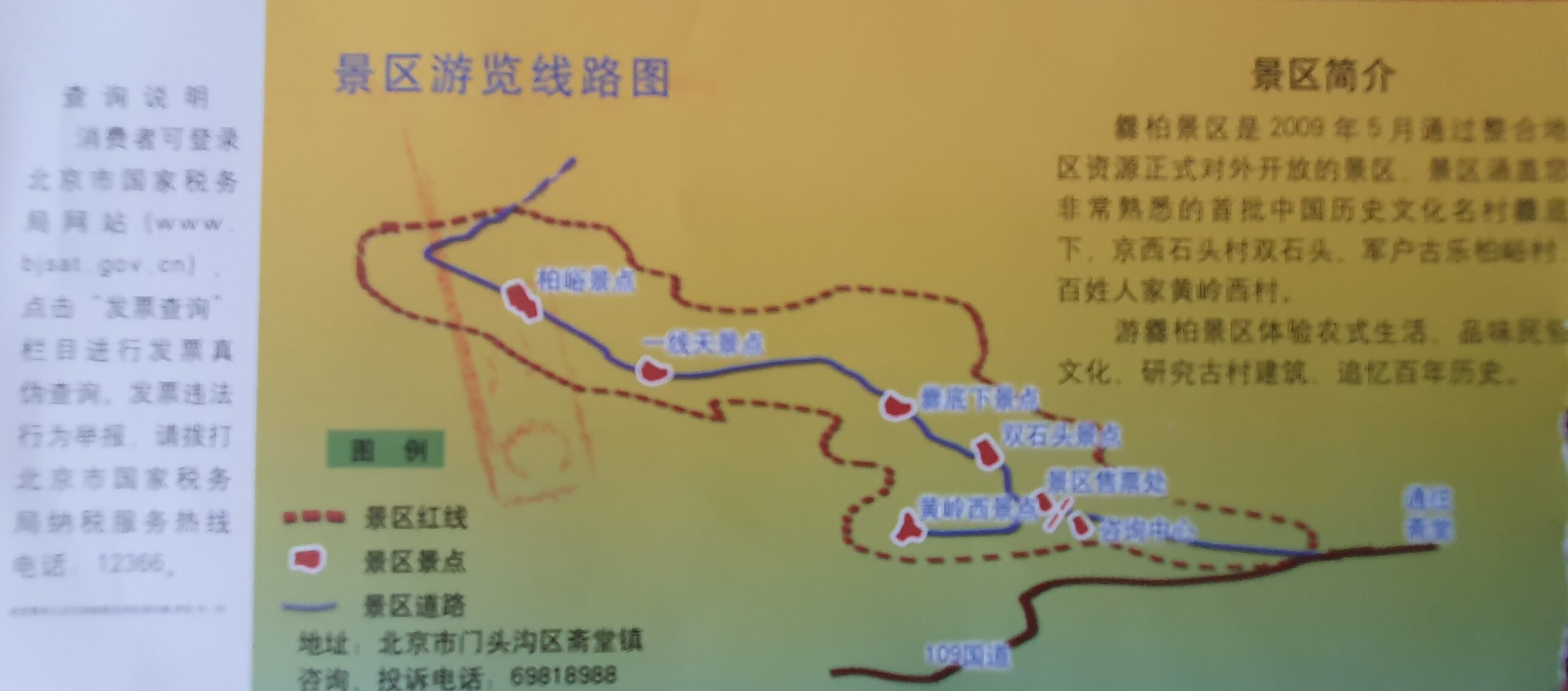

Cuandixia is located on ancient post road roughly 90 km northwest from central Beijing in the Jingxi mountain region. The village is served by National Road 109 and can be reached via bus line M 22 (previously this had been line 929 according to my to old travel guide) which departs from Pingguoyuan subway station. Travel from central Beijing takes about three hours by car (120 kilometers) (which is depicted below):

Grey circle. Taoranting subway station; A. Pingguoyuan subway and bus station; B. Zhaitang Bus station; C. Cuandixia village

Do’s and Don’ts: Comparison of organized taxi tour versus public transport

The Wandelgek tried at 1st to organize a taxi, just like he had done for his travels to Mutianyu and the Summer Palace, but the price for such a taxi drive was quite steep. The travel organisation he asked to arrange this, charged 1500 yuan for visiting two locations during a day and The Wandelgek declined that offer (which was 500 yuan more than the two location visits of yesterday, which was roughly the same distance in kilometres) and then they made a new offer and charged 1250 yuan for visiting only Cuandixia (still 250 yuan more than the previous 2 location visits). Compare that with the distances: To Mutianyu and the Summer Palace was about 160 kilometers. To Cuandixia was about 120 kilometers. The Wandelgek declined that offer too.

The Wandelgek had been to China before and remembered that taxi charges in rural areas where much less than they apparently were in Beijing and he also remembered the cheap public transport that was available. He decided to visit just one location and use public transport as much as possible to get there. This is what he subsequently did pay and save to reach Cuandixia:

Calculation

- 1st he walked for half an hour to the nearest metro tube station. Charge: 0 Yuan.

- 2nd he took the metro from Taoranting to Pingguoyuan (about 1hr one way). Charge: 10 Yuan (incl. return ticket).

- 3rd he took a busticket from Pingguoyuan station to Zhaitang (about 4.5 hrs, 3 hrs uphill to Zhaitang and 1.5 hrs downhill return). Charge: 30 yuan (incl. return ticket).

- Finally he bought a taxi ticket from Zhaitang to Cuandixia. Charge: 80 yuan (incl. return ticket).

- Total charge: 120 yuan.

All other charges like entrance fee (40 yuan) to the village, food and drinks would also have to be paid additionally when The Wandelgek had chosen to pay the 1250 yuan charge.

So The Wandelgek saved 1250 (=160 Euro) – 120 yuan = 1130 yuan, which is €145 (1130/7.8)!!!😱

Metro

After the walk The Wandelgek entered the Taoranting Subway station…

…and bought a one way metro ticket for 5 yuan which is valid in all of Great Beijing.

His travelguide which was a rather old one did have a map of the Beijing subway system…

…but the maps at the subway station were much more detailed and covered a larger area of Great Beijing.

The little red circle is Taoranting Subway Station. The Wandelgek boarded a metro towards Xidan Subway Station where he changed from the blue onto the red line and went from there all the way to Pingguoyuan Subway Station.

In the metro carriages are signs that show all stations

Most commuters are sitting or standing, meanwhile watching their mobile phone screen…

Bus

After leaving Pingguoyuan Subway Station, The Wandelgek needed a bus connection to Zhaitang. His older travelguide from the year 2008, which was the year when Beijing hosted the summer olympics, mentioned busline number 929 to Zhaitang, but The Wandelgek decided to try and ask someone before boarding. Bus drivers and policemen all spoke Chinese but no English, so he looked around carefully whether he could see a young student and he did. He then adressed him in English and found that he spoke English very well.

Not only could he then point The Wandelgek towards the right busline M 22 but he also spoke to the busdriver and explained him what bus ticket I needed. Apparently I needed 2 tickest, a red one and a blue one to get to Zhaitang for 7 +8 = 15 yuan later I needed two more to return to Beijing…

and where I wanted to go and he made a phone call to a taxi driver which was already waiting for The Wandelgek at Zhaitang bus station. Wow. Really helpful and supportive😃👍

In my old travelguide they added chinese characters, for every mentioned destination, which was really helpful too for travelling solo in Beijing.

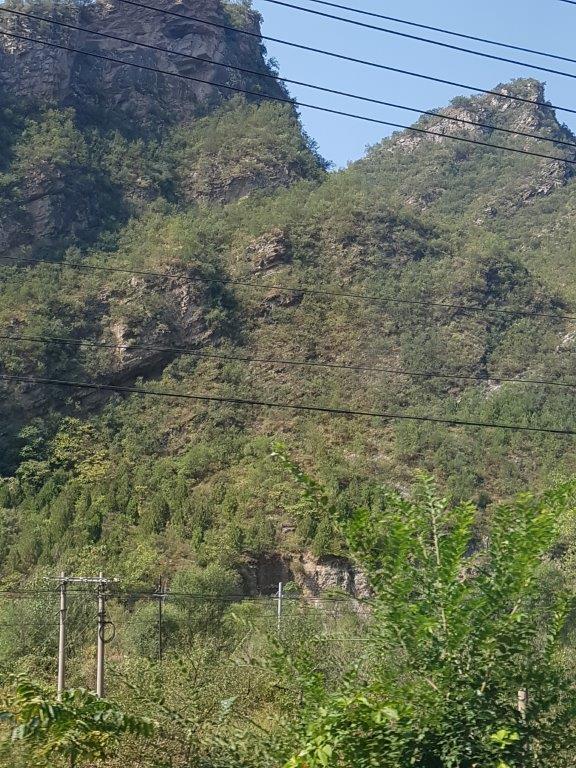

The bus drove for about 3 hours towards Zhaitang, which took so long because after driving through the outskirts of urban Beijing, the bus had to ascend many miles into the mountains north of Beijing. The road used one or maybe two river valleys, driving passed hydro electricity plants and lakes. The views were quite awesome…

These were the same mountains that The Wandelgek had passed through by train several days earlier.

Via Zhaitang

After arriving in Zhaitang, a taxi driver immediately addressed The Wandelgek, when he unboarded from the bus. He asked in Chinese whether The Wandelgek wanted to drive to Cuandixia, which was of course the only word that The Wandelgek could understand. The taxi driver had been informed by the student at Pingguoyuan station.

Cab/Taxi

It was only a 15 to 20 minute drive ascending further into the surrounding mountains from Zhaitang bus station.

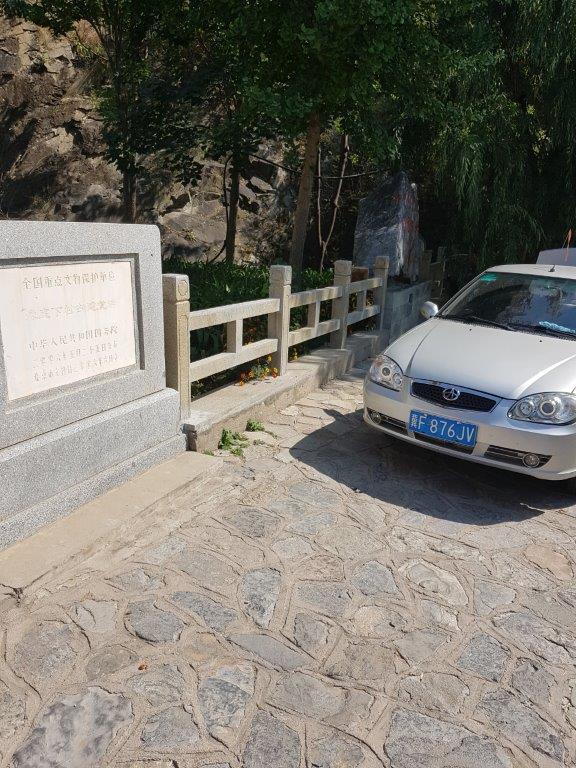

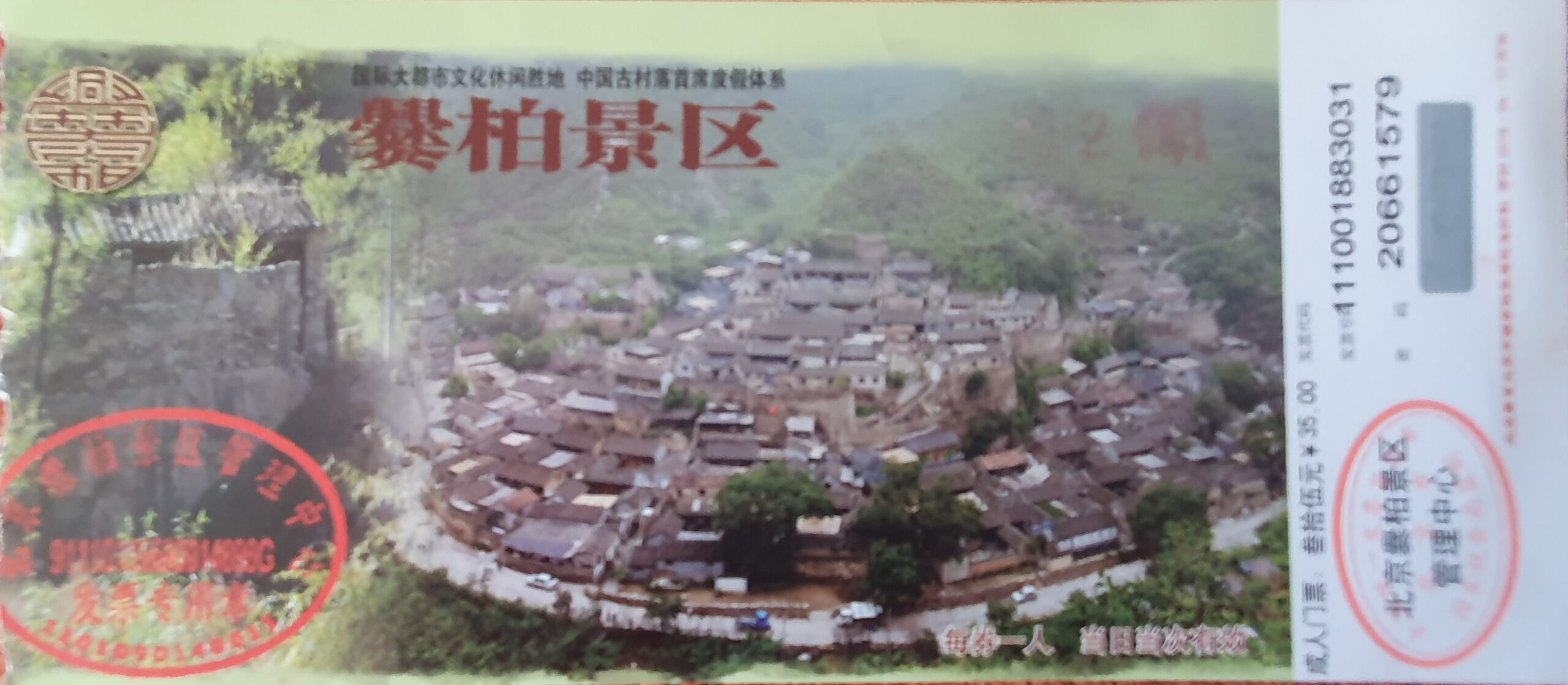

Near the village was a small building where the driver told The Wandelgek to purchase a 45 yuan entrance ticket for the village.

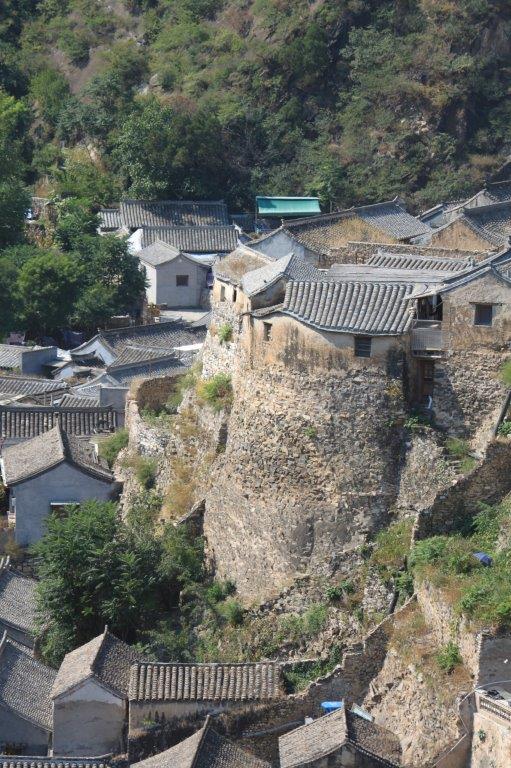

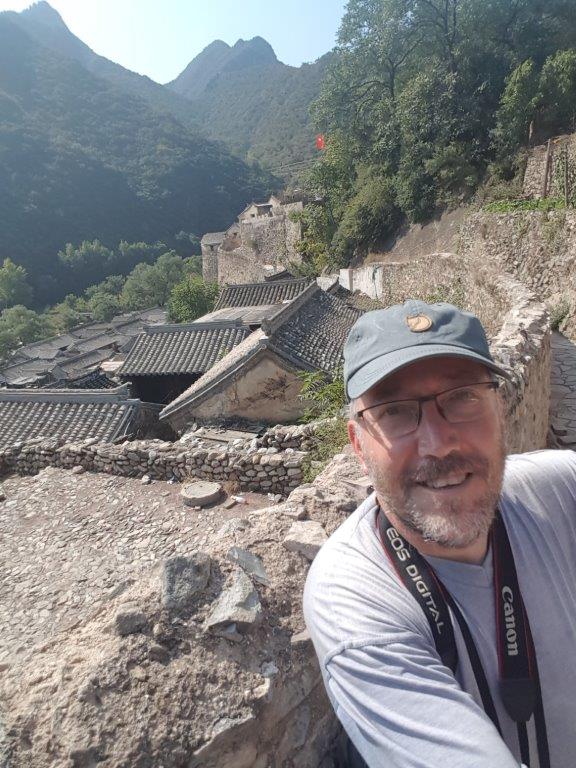

Then he drove to Cuandixia and dropped The Wandelgek on the main road, which was at the bottom of the steep valley. The largest part of the village was build against one of the steep slopes, while the other slope was green, full of trees.

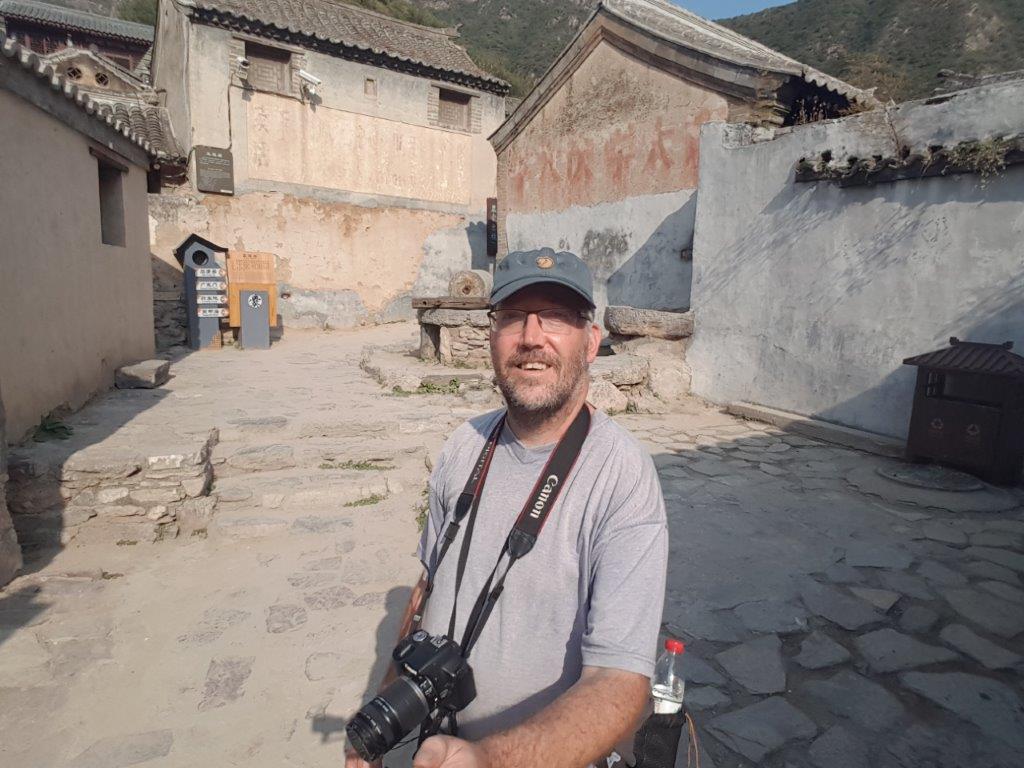

Cuandixia

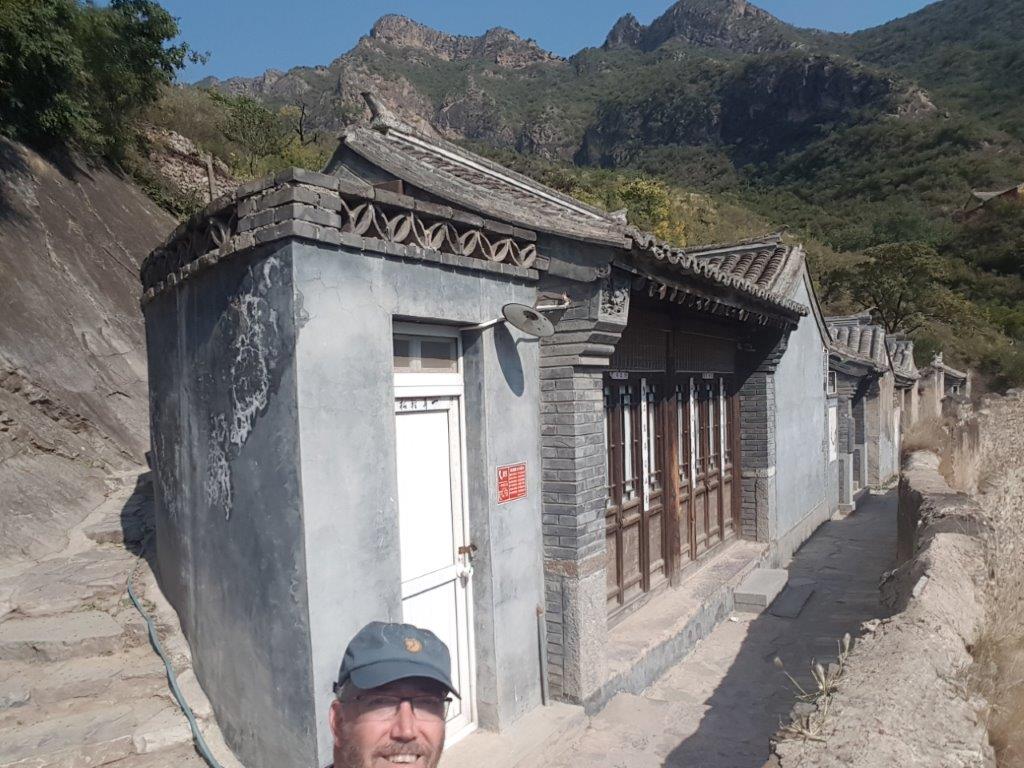

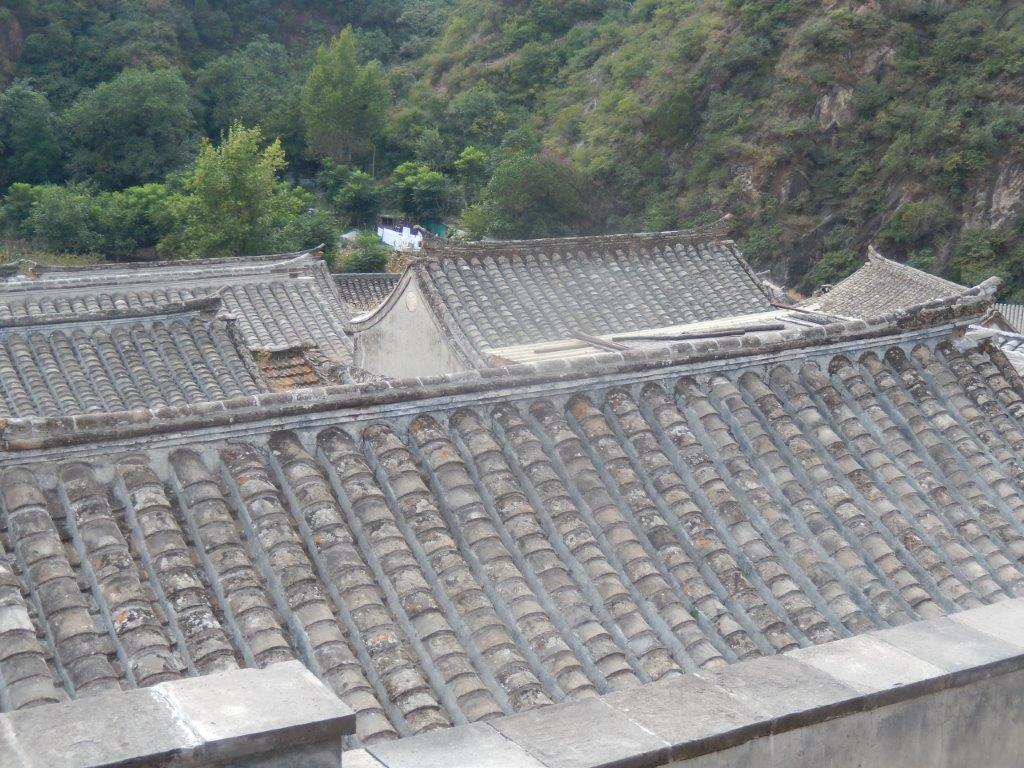

Cuandixia (Chinese: 爨底下村), also spelled Chuandixia (Chinese: 川底下村), is a historic village dating from the Ming dynasty located in Zhaitang (斋堂镇), Mentougou District in Beijing, China. It is a popular tourist attraction known for its well preserved courtyard homes.

Cuan (爨) means “cooking-stove” in Chinese. In the year 1958, it was simplified as Chuan (in Chinese: 川). The reason why this hamlet has this name is that the host would like to be away from chill. It is famous because it has a history of 400 years during the Ming Dynasty. At that time, Cuandixia’s settlers migrated from Shan Xi, a province west of Beijing. It is a stronghold on the way from Beijing to Shan Xi.

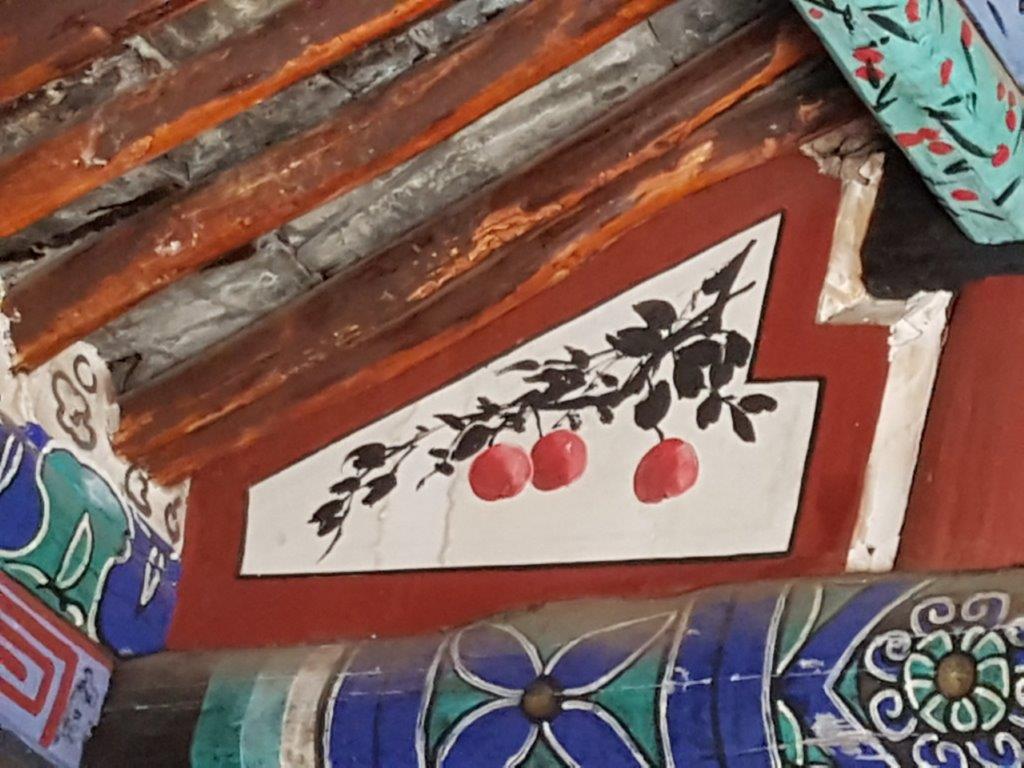

The family name of all of the villagers living here is Han (韩/韓), which means that they share the same ancestor. Hundreds of years old, the houses here still maintain the style of Ming and Qing Dynasty. Therefore, it is an attractive historical site, where thousands of people come here from its surrounding cities. There are 500 houses left. Stone carving, brick carving, calligraphy, and painting are everywhere. Common figures used are bats, pied magpies, Peonies, waterlilies, etc. Each of them has its typical meaning.

The site is a National Village Architecture Reserve.

Cuandixia was founded during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) by members of the Han clan who moved from Shanxi Province. Towards the end of the Qing Dynasty Cuandixia prospered from trading in coal, fur, and grain.

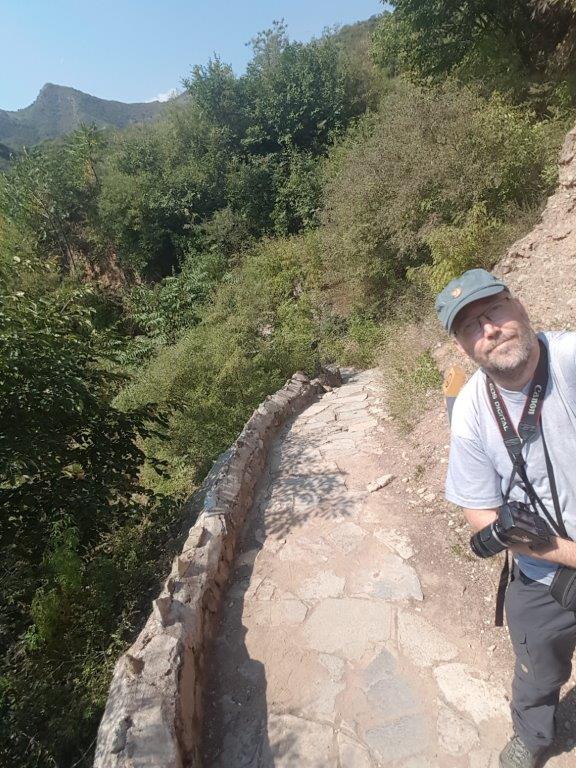

The surrounding area is full of mountains and trails for hikers, which was one of the main reasons for The Wandelgek to visit it too. See my next blogpost for a hike in the village surrounding forest and hills.

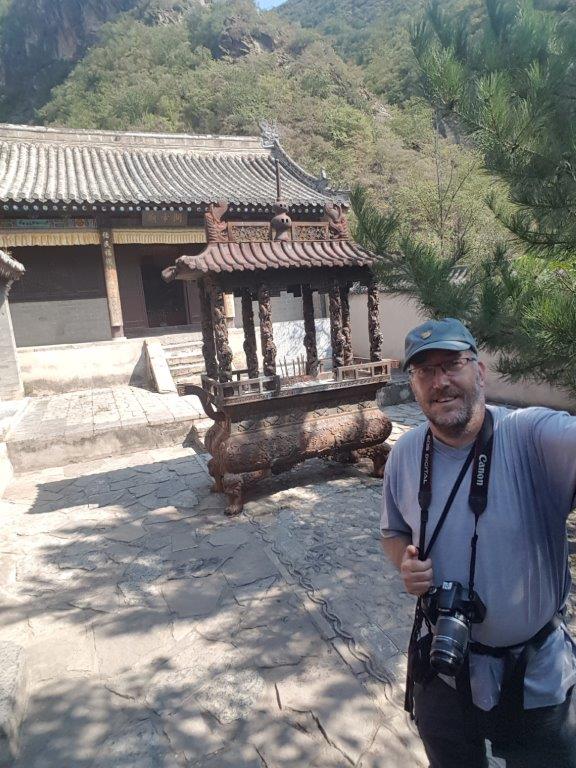

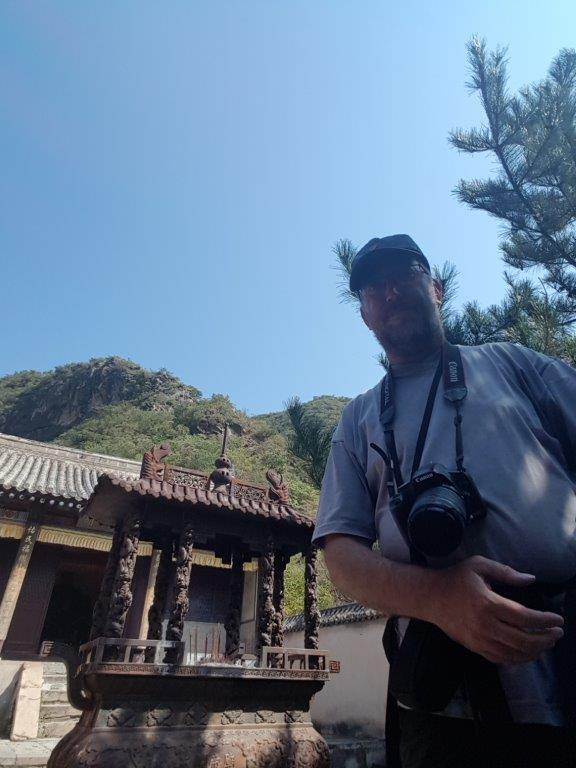

Climb to a little temple

From the central road in the vale, a small trail went straight up the mountain towards a tiny temple. The weather was brilliant and the views from the trail were very promising of what would still lie ahead…

Temple visit

Exterior

The temple was quite small but it immediately looked genuine and not restored or anything. Not sure whether it really wasn’t, but if it was restored or restorated, than they did a magnificent job…

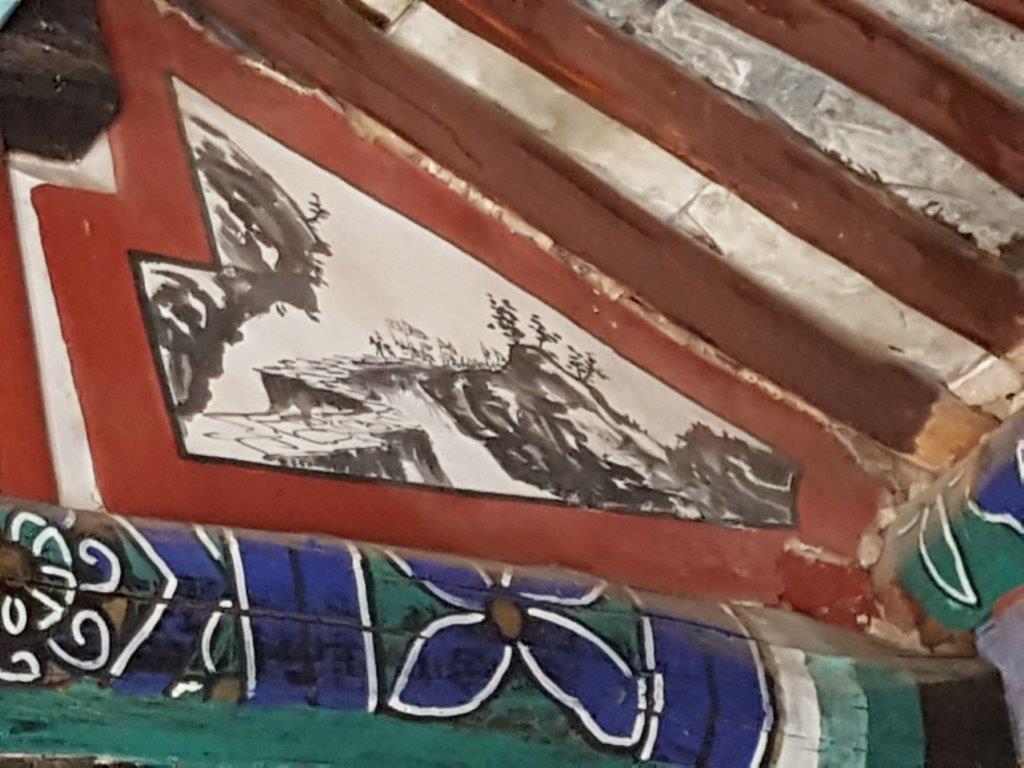

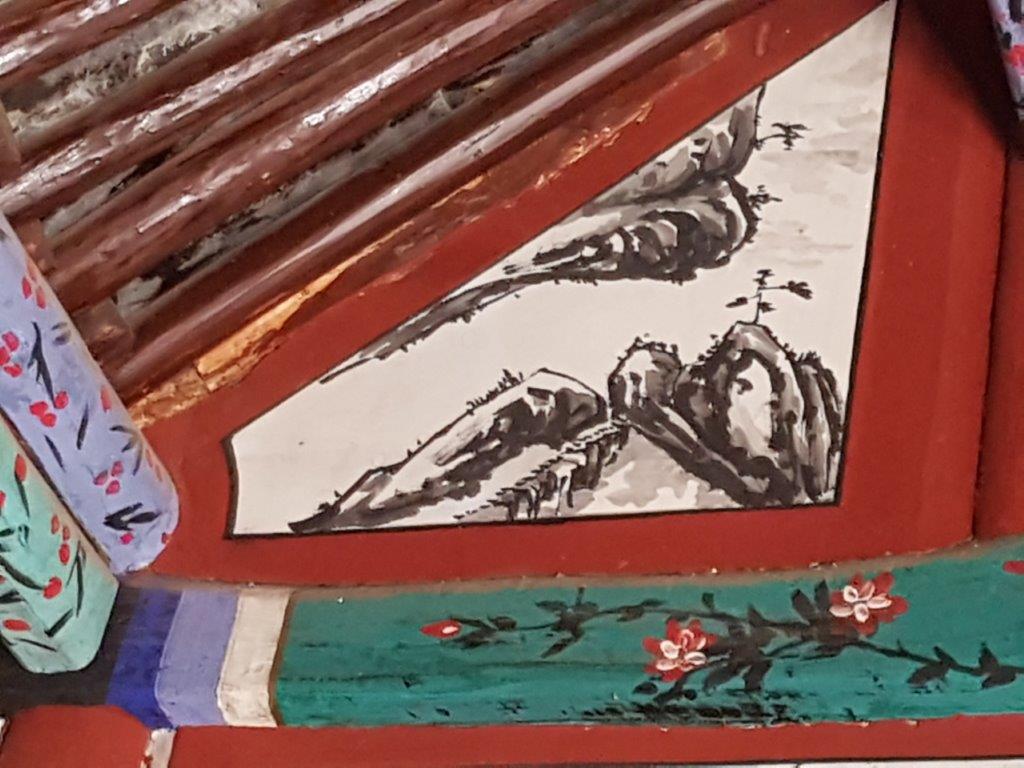

Interior

Inside it was beautiful, like walking into a chinese arthouse movie set. I mean that this could easily become a set for one of the great chinese director Zhang Yimou’s movies that were very popular in Europe too. The Wandelgek loved the chinese style windows and the little decorative paintings mostly on wooden roof beams or decorative panels between those wooden beams. Some paintings looked very delicate…

Statues and offerings

In some rooms of the temple were statues of deities and even a little altar where small offerings could be left behind…

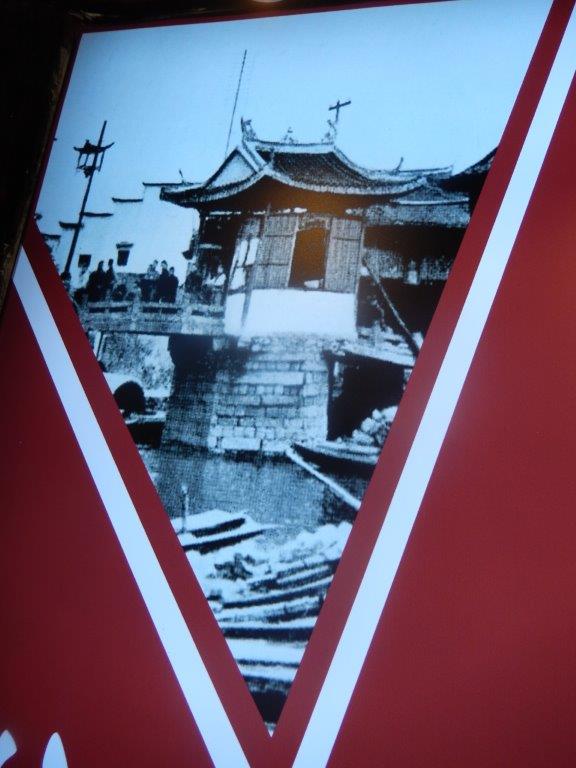

A tiny pavillion and a view

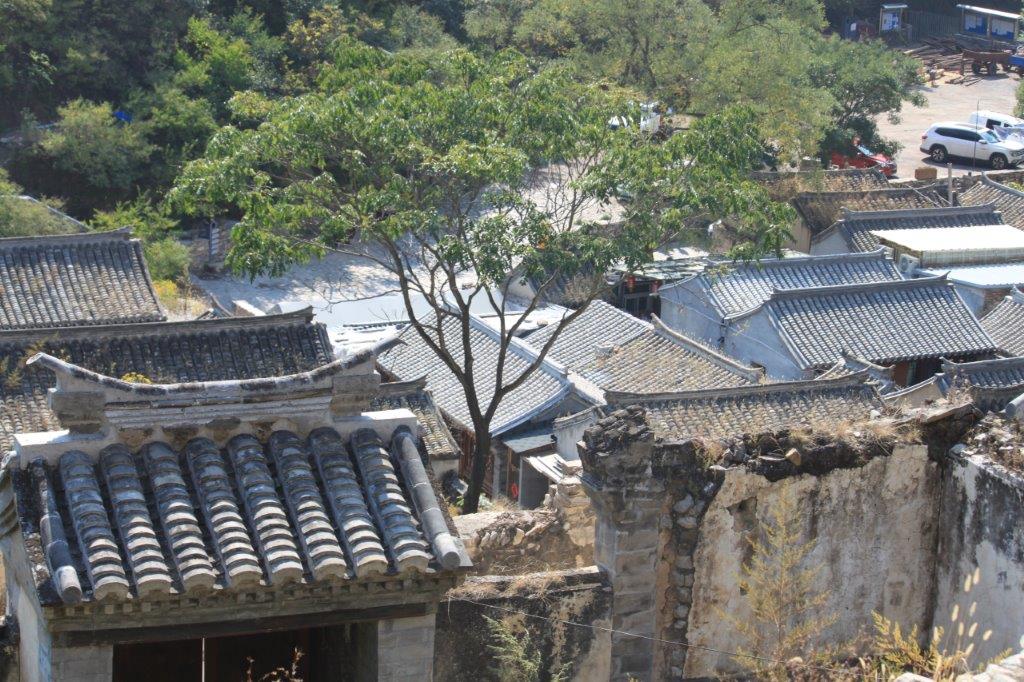

Outside of the temple at the verge of the slope was a viewpoint where a small pavillion was located, from where The Wandelgek had a wonderful view over the valley, the surrounding mountains and over the village of Cuandixia…

Above you see the pavillion which is rather typical for Chinese garden design which started when the imperial Tang dynasty was in power. The pavillion is designed to give the viewer that stands in it an almost unobstructed view over his surroundings and therefore it is located in a beautiful place and the visitor’s view is directed towards the best possible view…

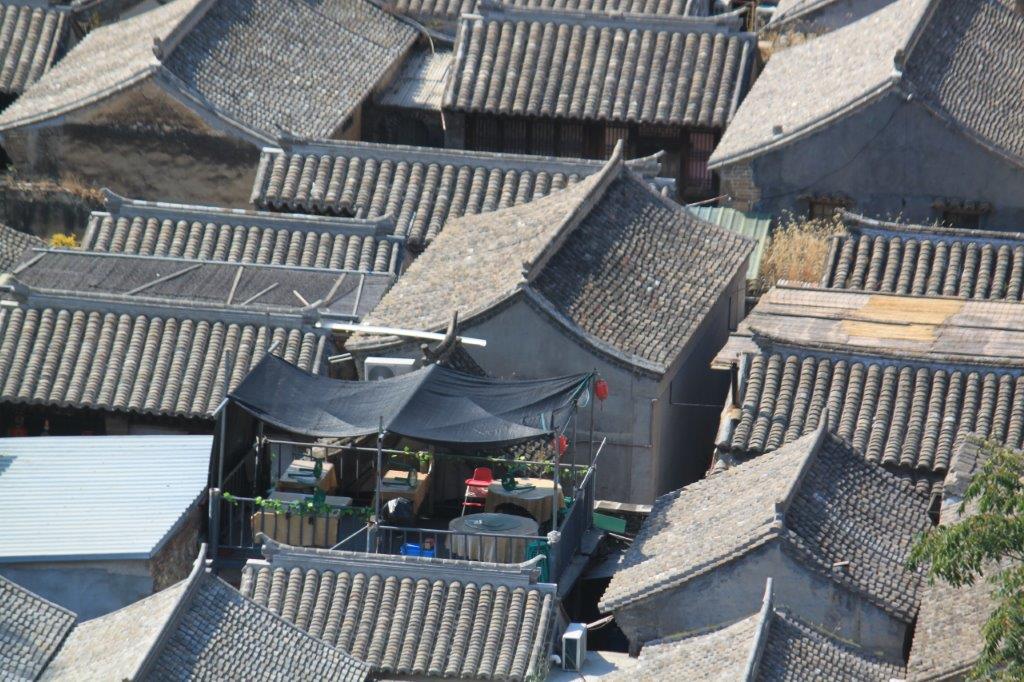

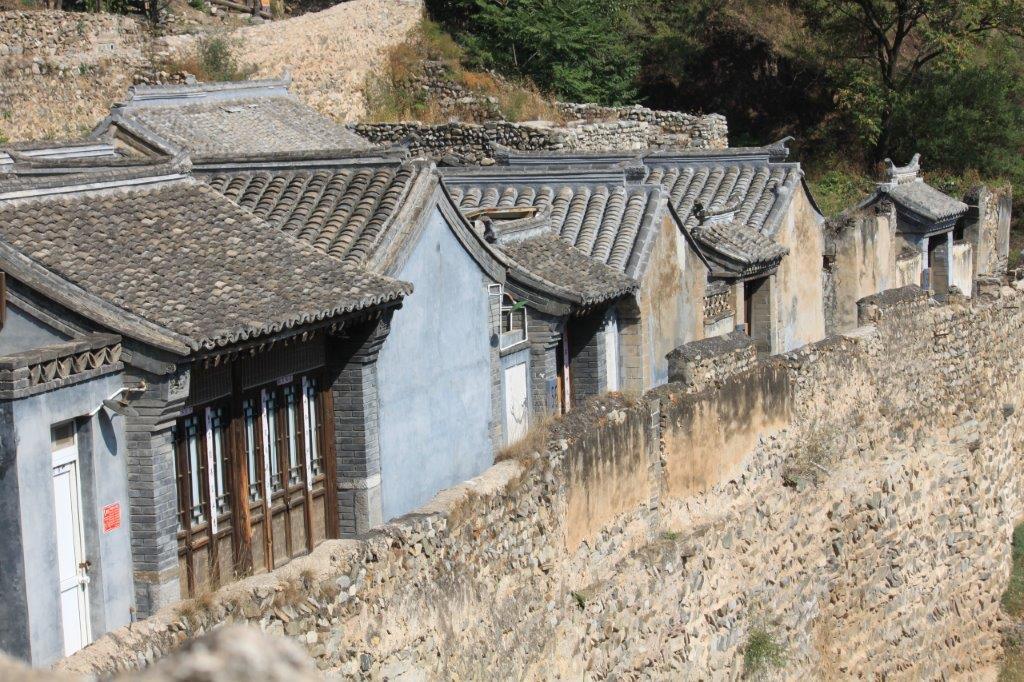

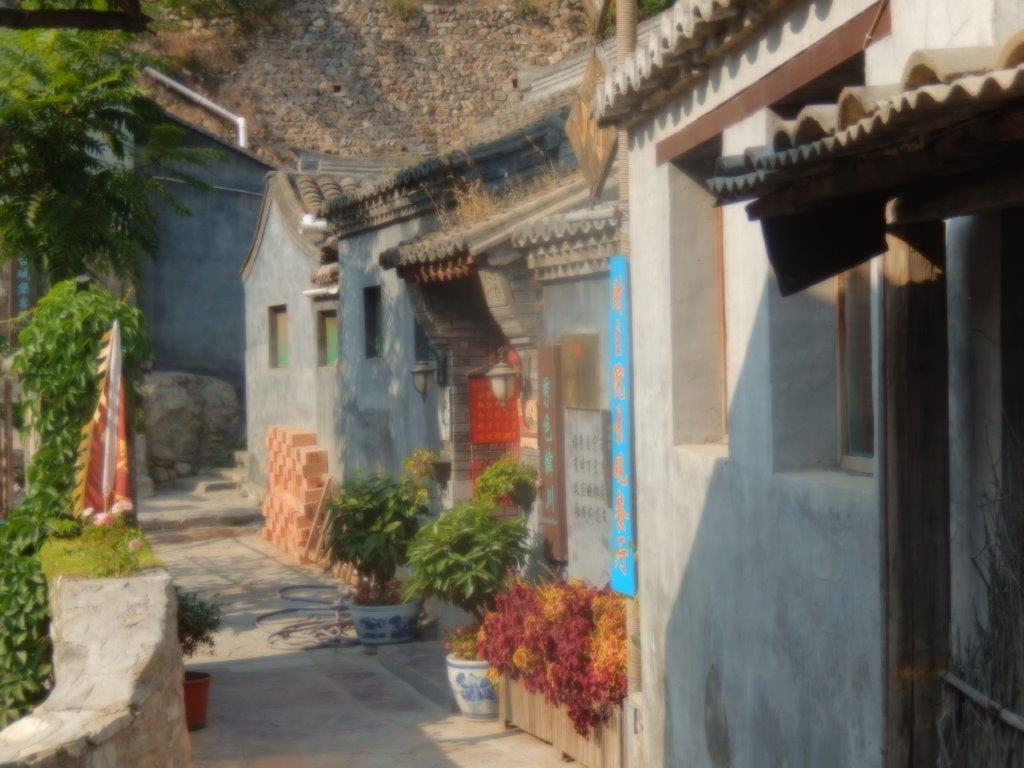

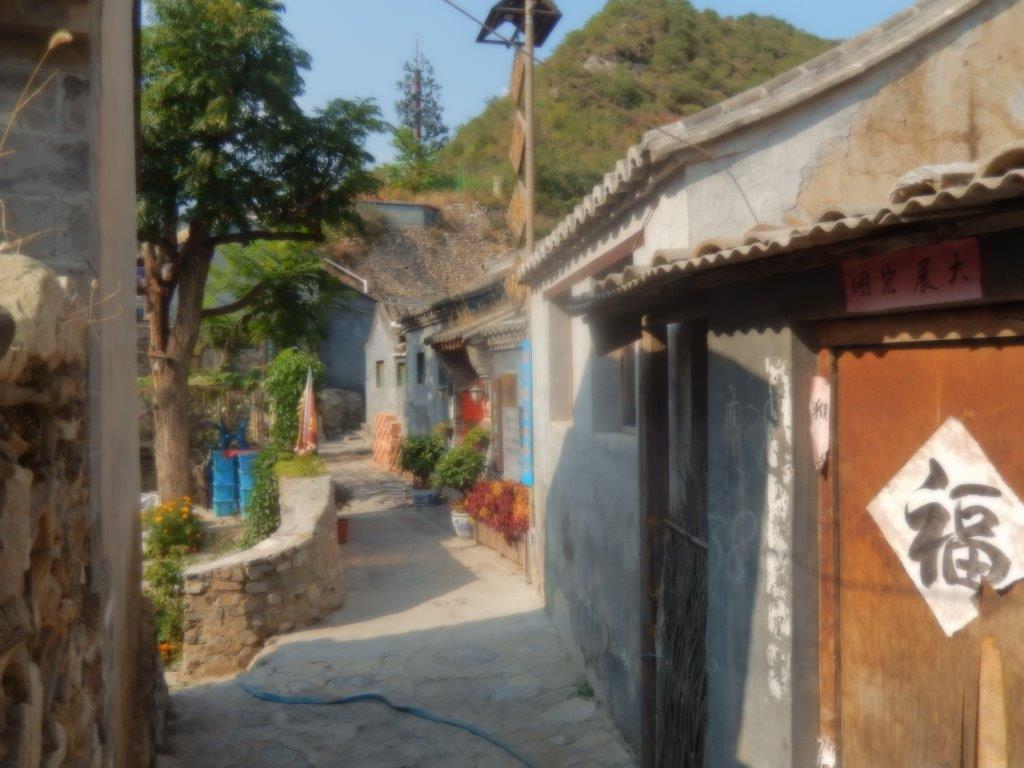

Cuandixia is home to 500 well preserved courtyard homes dating to the Ming and Qing dynasties. Many of these homes have been converted into inns offering food and lodging to travelers. Stone paved lanes and steep staircases help define Chuandixia’s architectural identity. The village is a frequent subject of photographers and painters. The surrounding area is full of mountains and trails for hikers (see my next blogpost for one such a trail).

The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was the ruling dynasty of China from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last imperial dynasty of China ruled by Han Chinese. Although the primary capital of Beijing fell in 1644 to a rebellion led by Li Zicheng (who established the Shun dynasty, soon replaced by the Manchu-led Qing dynasty), numerous rump regimes ruled by remnants of the Ming imperial family—collectively called the Southern Ming—survived until 1662.

The Qing dynasty, officially the Great Qing, was the Manchu-led last dynasty in the imperial history of China. It was proclaimed in 1636 in Manchuria (modern-day Northeast China and Outer Manchuria), in 1644 entered Beijing, extended its rule to cover all of China proper, and then extended the empire into Inner Asia. The dynasty lasted until 1912. In orthodox Chinese historiography, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the Ming dynasty and succeeded by the Republic of China. The multiethnic Qing empire lasted for almost three centuries and assembled the territorial base for modern China. It was the largest Chinese dynasty and in 1790 the fourth largest empire in world history in terms of territorial size. With a population of 432 million in 1912, it was the world’s most populous country at the time.

As The Wandelgek was enjoying the magnificent view from the small pavillion over the village and the surrounding mountains and while he spotted some trails going up those mountains, he suddenly noticed this intricate web and a tiger tarantula (I’m imagining that name on the go🙃). It was busy conserving some previously caught insects.

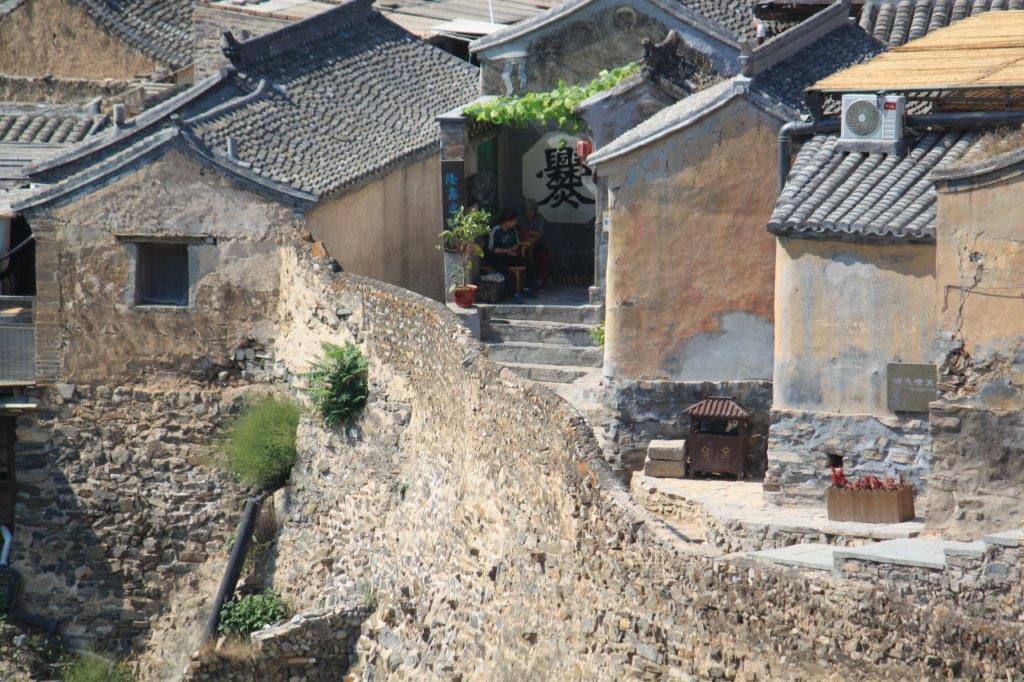

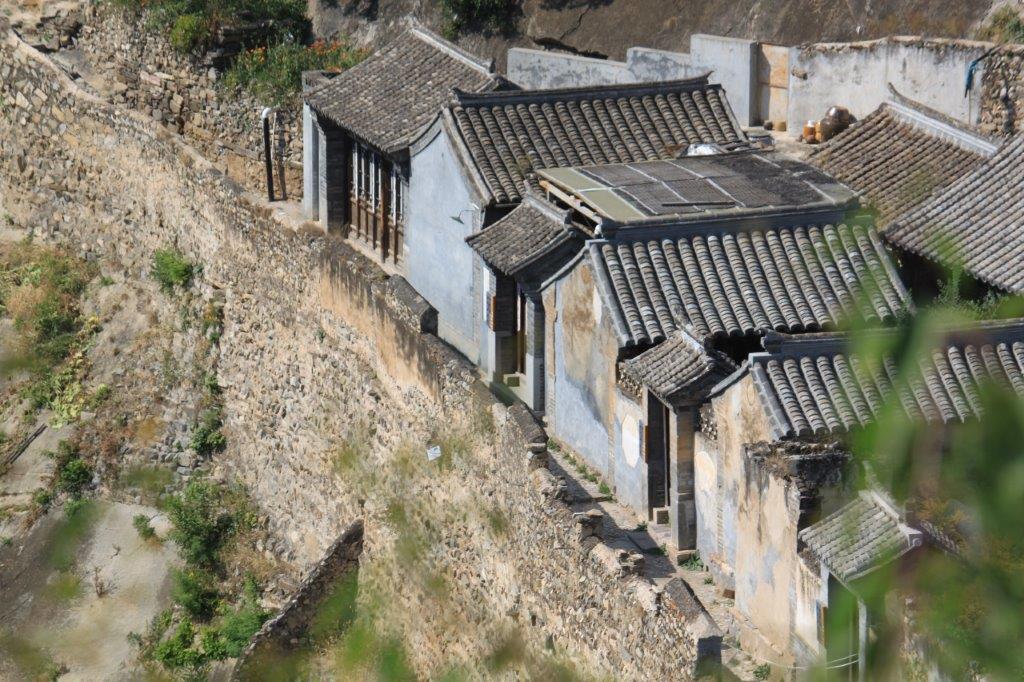

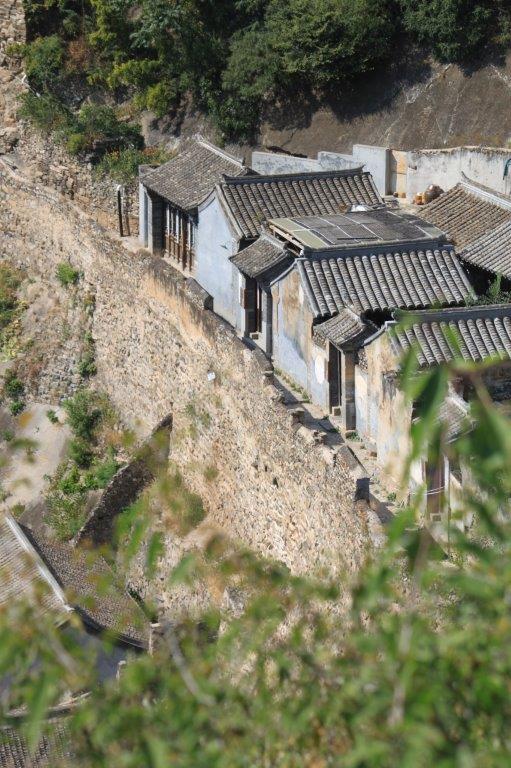

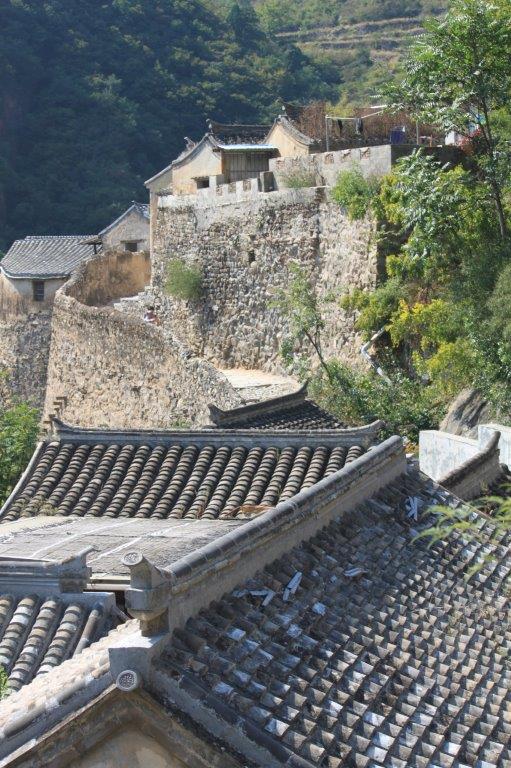

From the pavillion the view over the village was quite phenomenal. Like e.g. over this little street with old houses on top of a wall, which I had spotted in my travel guide and which had immediately atracted me towards Cuandixia…

Walk towards the upper part of Cuandixia village

Not quite sure what crop or fruit was farmed here, but I loved the views.

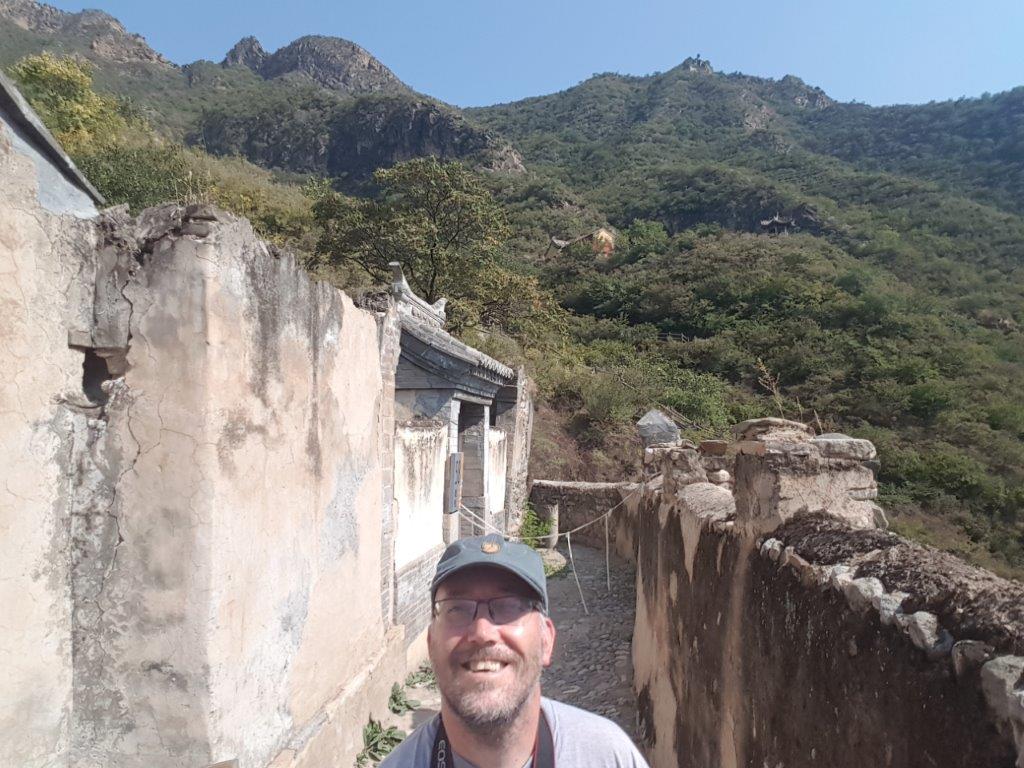

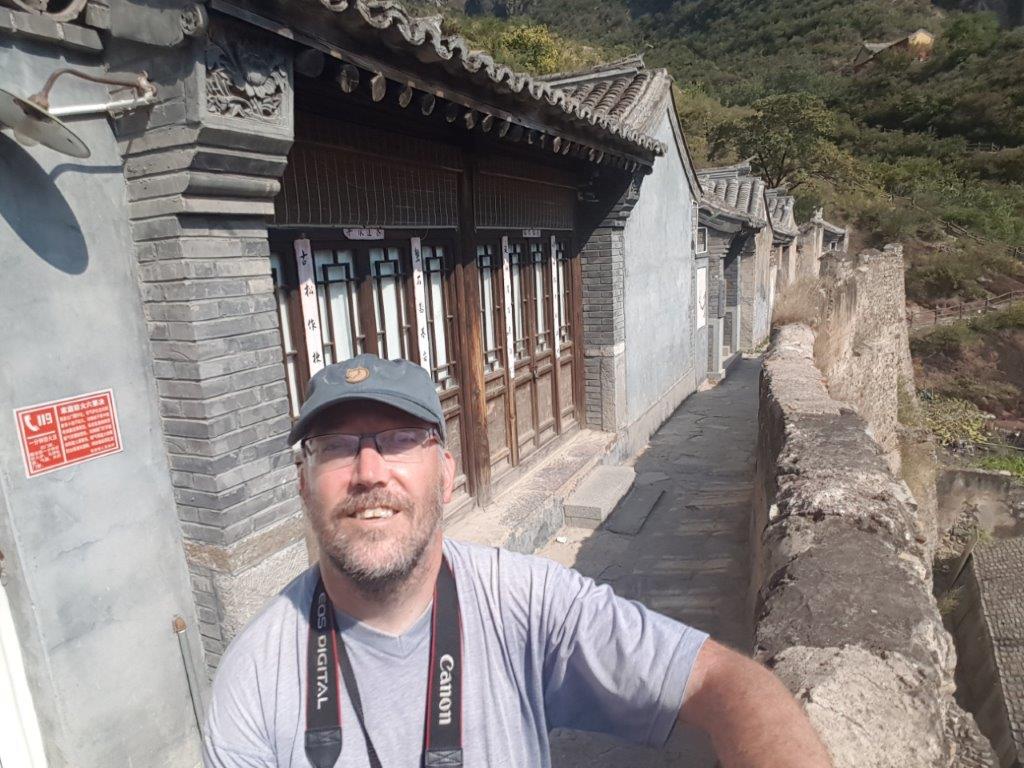

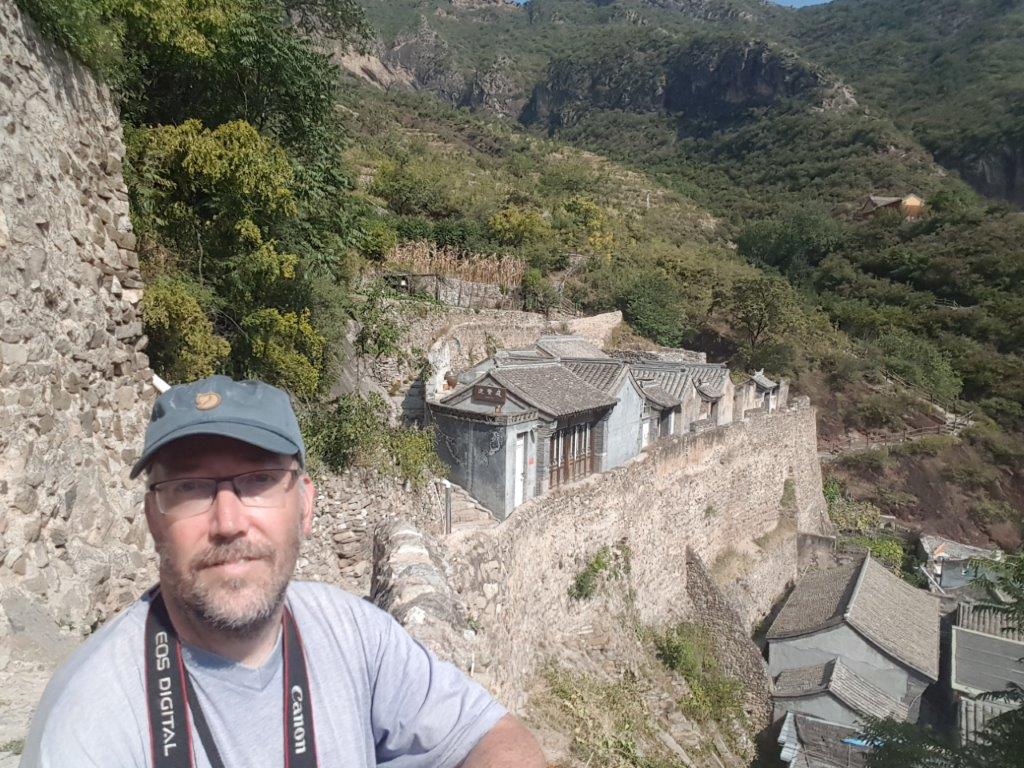

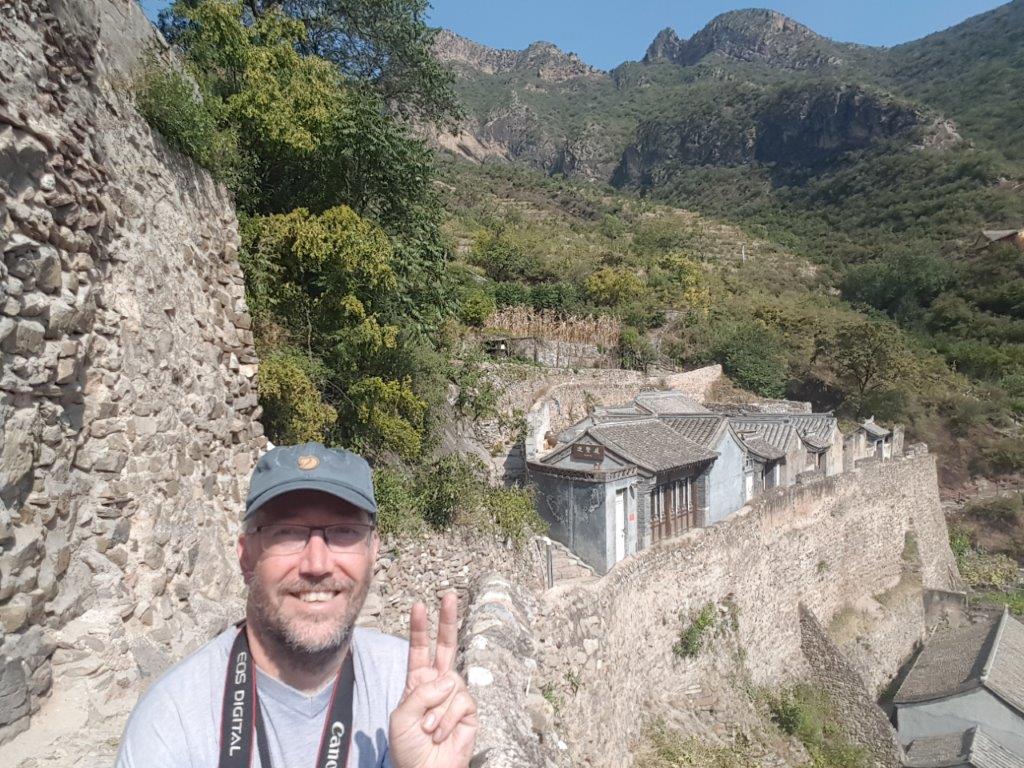

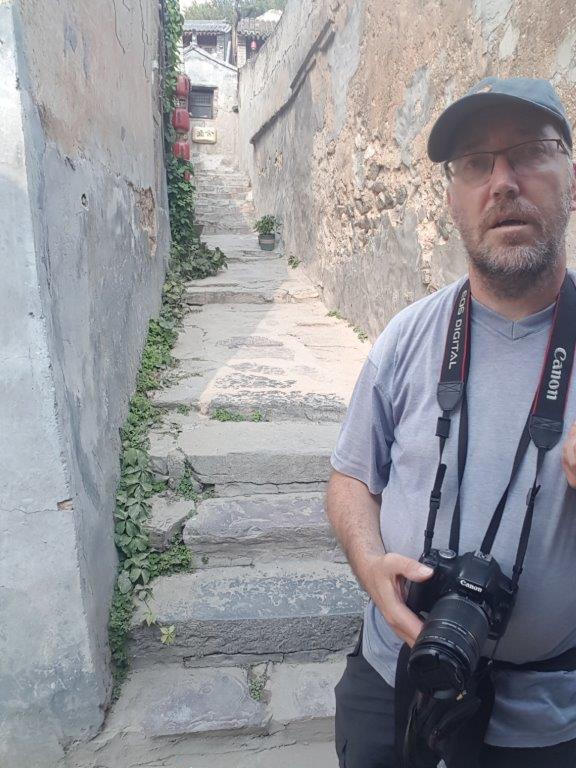

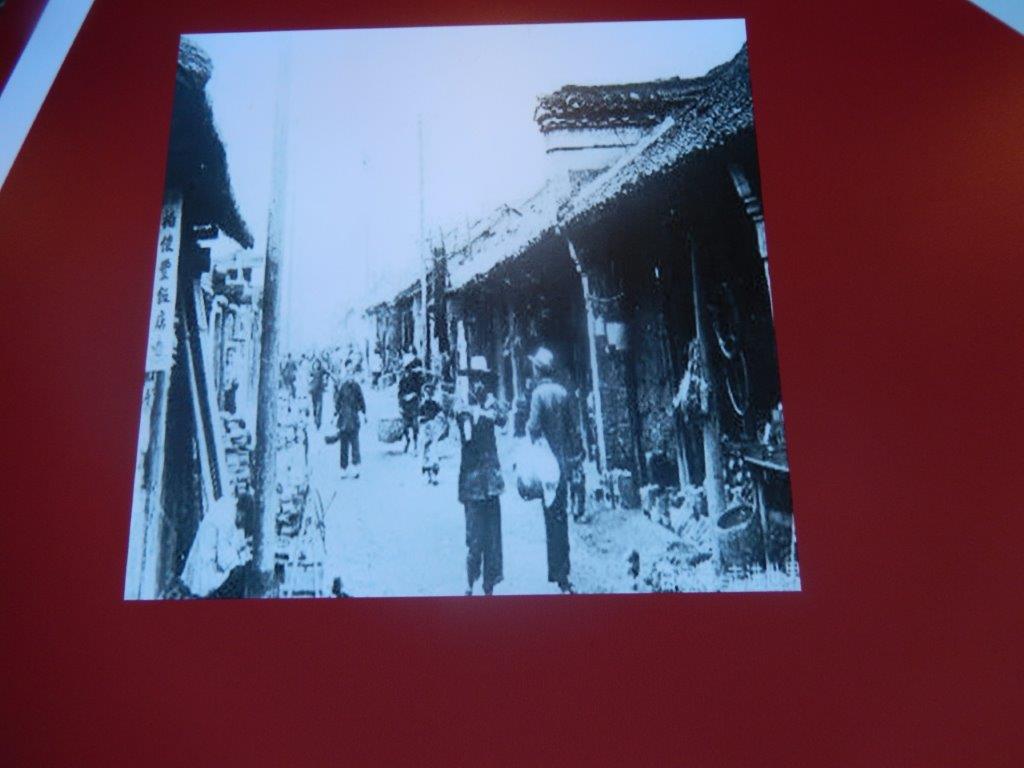

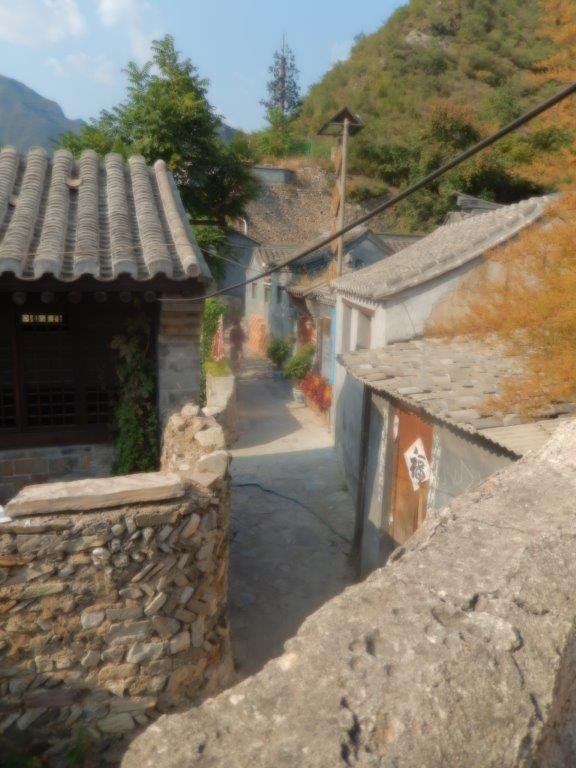

And then The Wandelgek reached the small ancient street that had atracted him towards this village in the 1st place. It still looked cool….

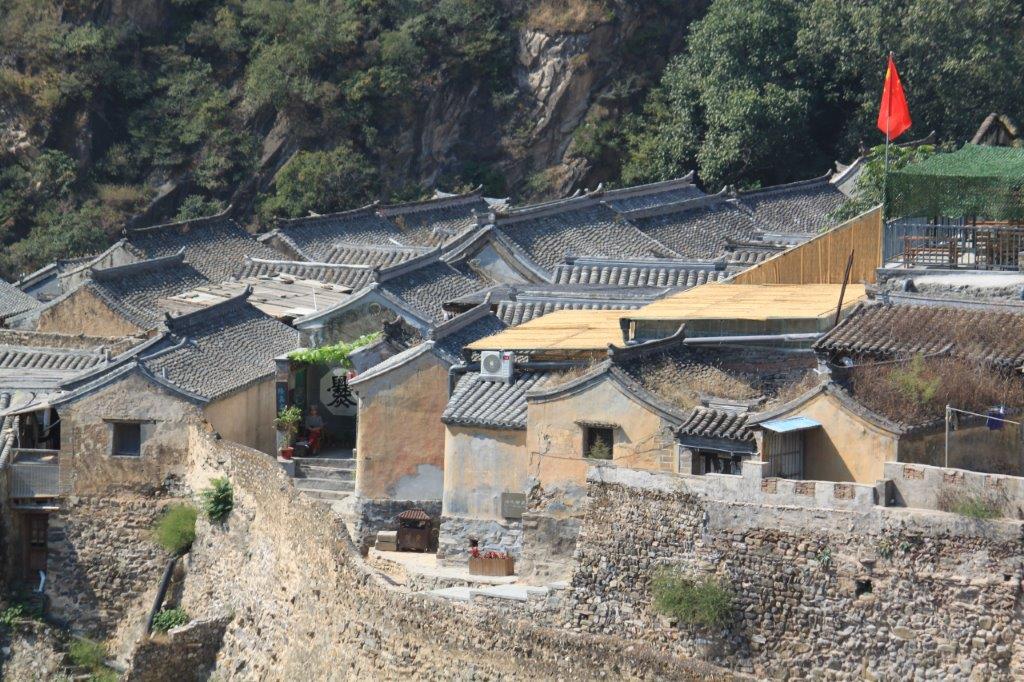

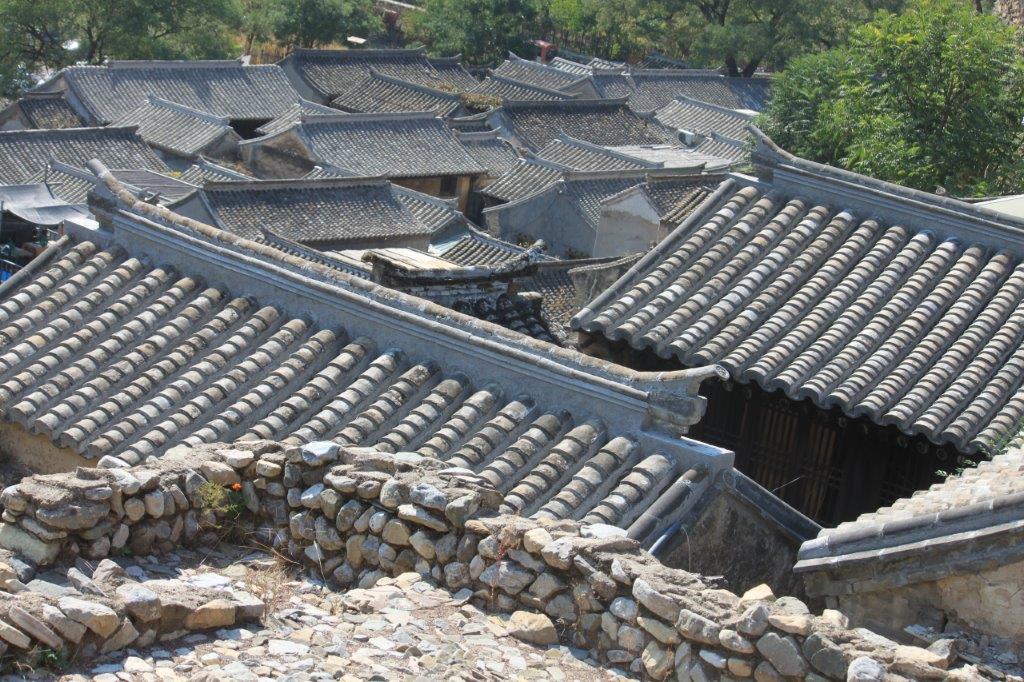

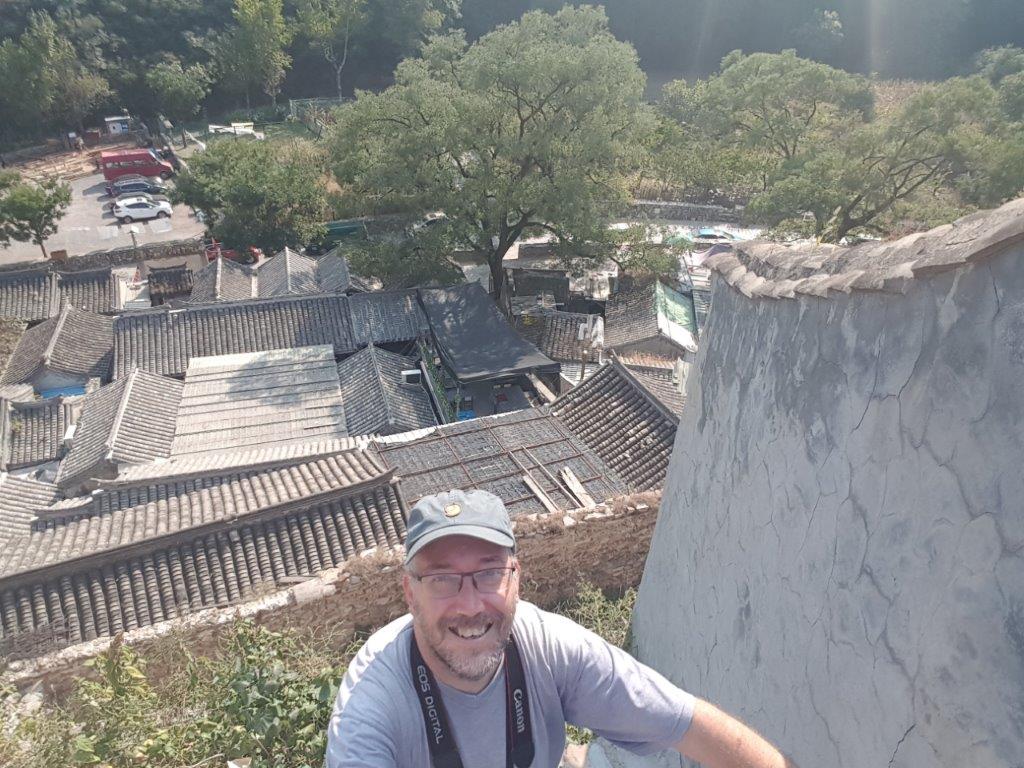

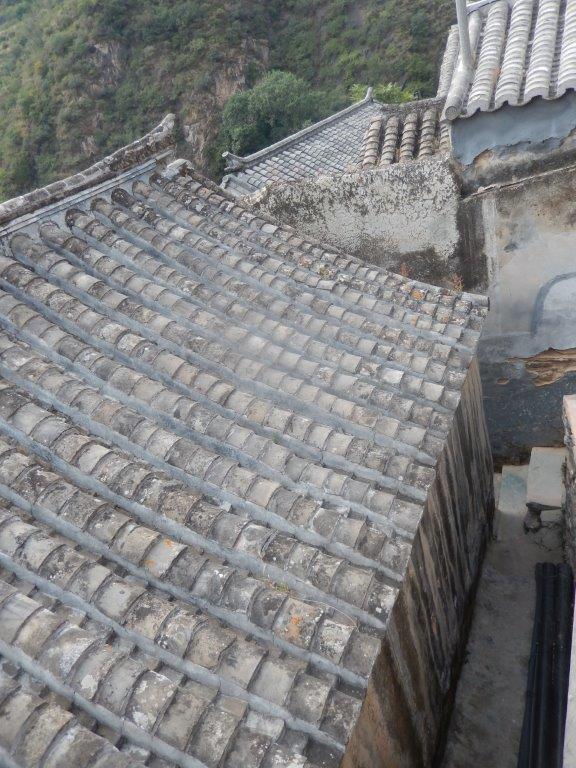

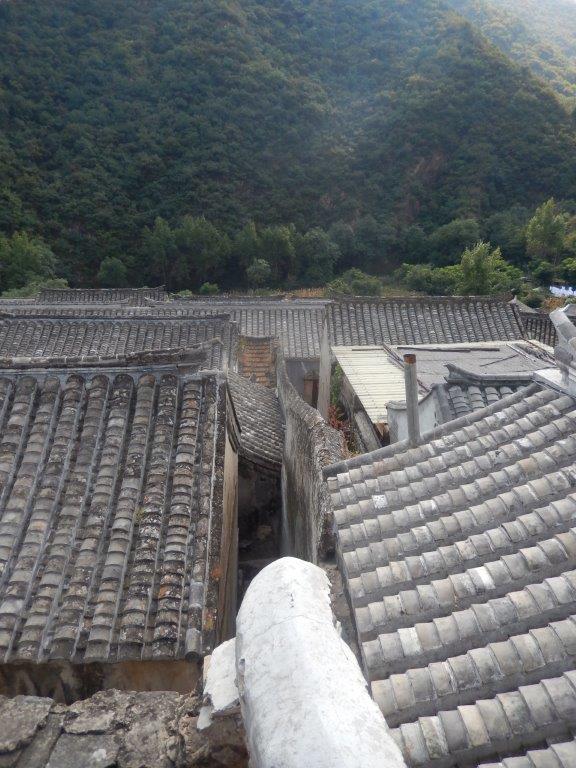

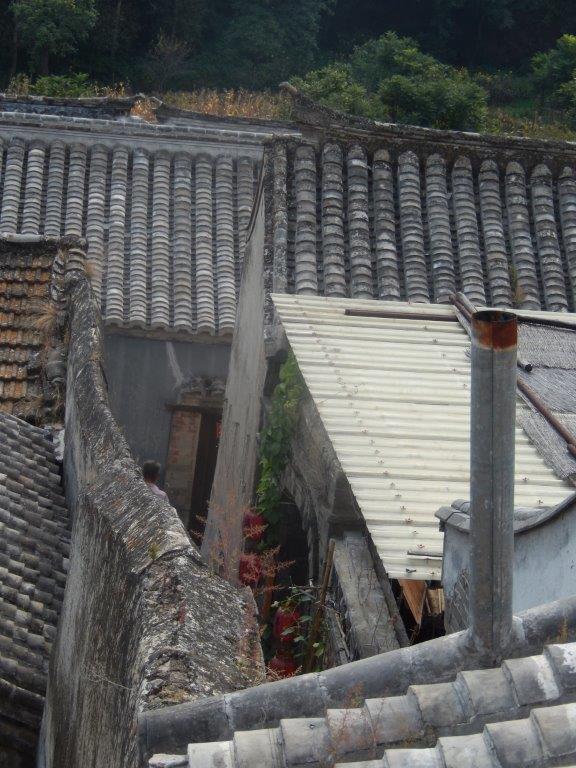

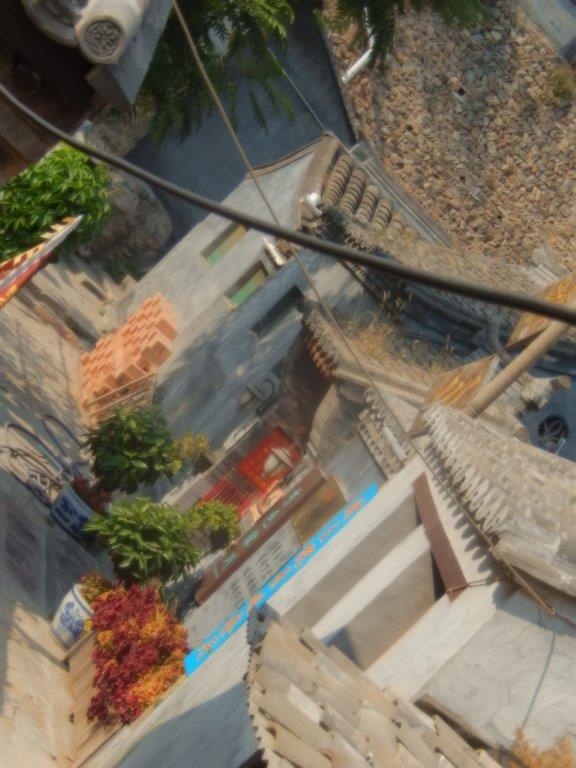

From this high spot, the view on top of the many roofs was awesome…

A last look back towards the street on top of a wall…

The Wandelgek walked deeper into the village, which really felt like walking back into time, into Chinese history. The village was quite intact. He passed a house with an old courtyard where an old lady asked him inside for food and drinks. It was a very basic backpacker restaurant and The Wandelgek liked what he saw. There was a room where backpackers could stay the night, sleeping in their sleeping bags on the floor. Years ago, The Wandelgek would have absolutely made use of this and he would’ve spend the night for a small fee, but now he was returning to the Beijing city center later that day, because he had an early plane to catch on the next morning.

Eating rural chinese food

The Wandelgek had seen this chinese sign and some local ladies sitting in front of it from afar. He decided to have a look…

It appeared to be a backpacker joint for people who visted the village and wanted to do some multiple day hikes in the mountains as well. They had a room with lots of sleeping bags all over the floor. Cool place! Instead of staying the night, The Wandelgek decided to have lunch here and drink a beer. It was quite hot in Beijing and the ascends had made him hungry as well as thirsty. Staying the night would have been really cool, just like years ago, but he had a plane to catch very early next day. However, the backpacker joint had a small, cozy courtyard which looked very old and he decided to sit there in the shade and ordered some food.

Red lanterns were hanging from the roof and there was a fish tank containing some bright colored fish.

He looked around at the construction and decorations…

He had ordered a chicken soup with mushrooms and vegetables, an apple and a plate of spiced peanuts.

Now for those of you who have never been to china: Chicken soup in China is quite different from chicken soup in Europe or the US. Where we have gotten used to the chemically flavored chicken soup which most of the time does not even contain any chicken, the Chinese have real chicken soup as it was made in Europe before WWII. Meaning that it is a complete chicken, with head and claws in it, from which the soup is created.

The Wandelgek however had been to China several times before and knew perfectly well what he had ordered…Yummy😋

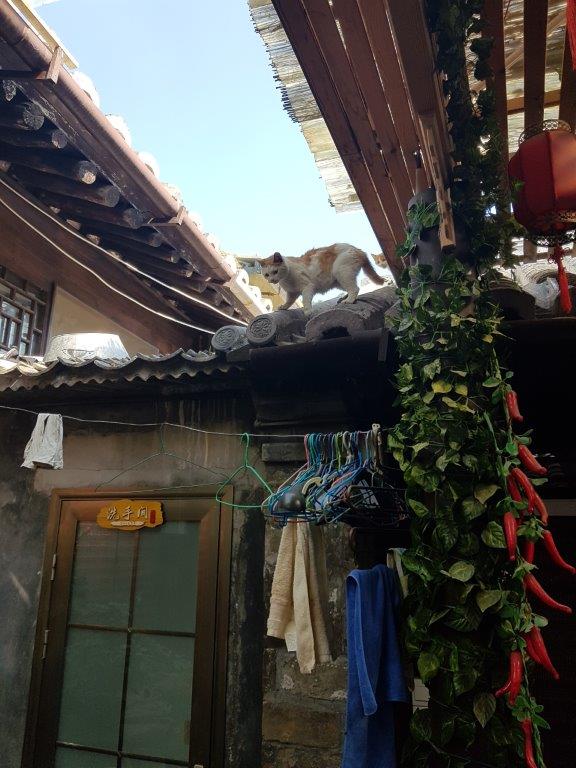

The neighboring cats began to show an interest for The Wandelgek’s lunch🤣

Between the laundry there were alse red peppers, drying in the sun…

Everything felt laidback, relaxed, no fuss, “don’t do today what can be done tomorrow”, tranquile…

… and drinking a cold local Chinese beer, The Wandelgek felt he had made the right decission to stop here for lunch, a local Yanjing beer and even more than that: a break😃

Beijing Yanjing Brewery is a brewing company founded in 1980 in Beijing, China. Yanjing Beer was designated as the official beer served at state banquets in the Great Hall of the People in February 1995.

Beijing Yanjing Brewery is a brewing company founded in 1980 in Beijing, China. Yanjing Beer was designated as the official beer served at state banquets in the Great Hall of the People in February 1995.

The company produces a range of mainly pale lagers under the brand name Yanjing.

After drinking a beer, a toilet visit is obligatory 🤣🙈

There was a tiny, very basic/primitive toilet in one corner of the courtyard and before leaving onward, The Wandelgek went through his knees and used it…😉💩

Than he thanked and said goodbye to the older chinese lady and went on for…

A stroll through a village frozen in time

The Wandelgek was now slowly descending through these alleys and visiting some of the courtyards and buildings en route…

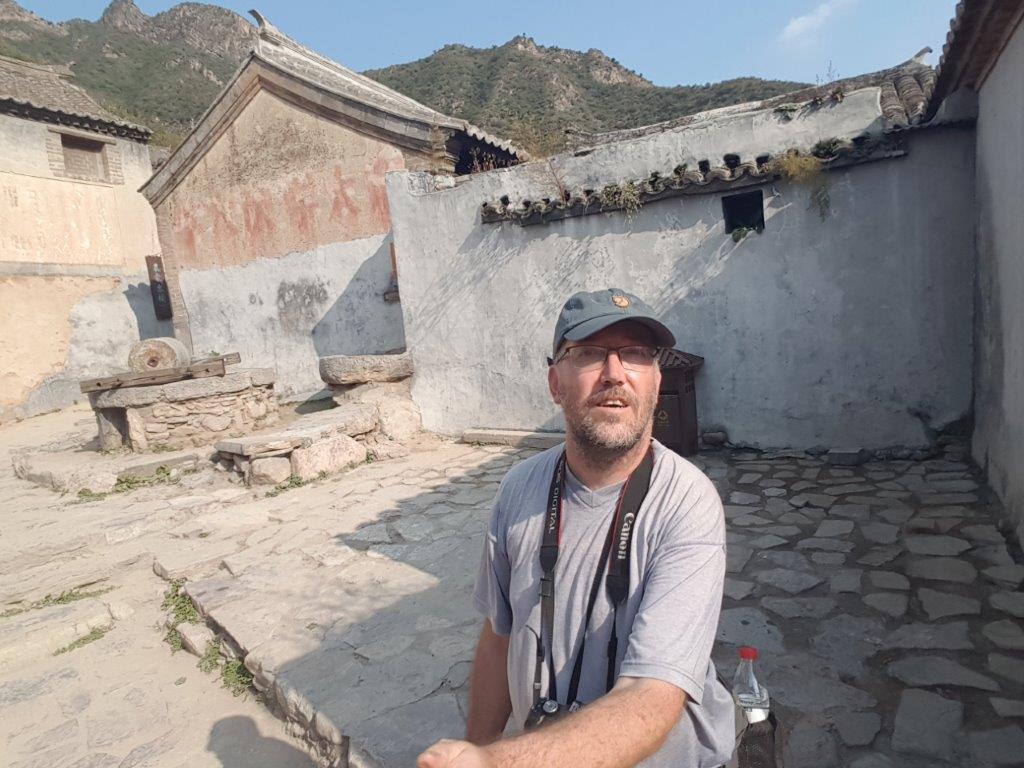

Maoist slogans and cultural revolution propaganda on walls

Cuandixia felt frozen in time and this was because of its remote location deep in the mountains surrounding Beijing. Because of this, it had not been discovered by foreign travellers and tourists, until fairly recently. But it had also escaped from the attention of the regime. Most other villages originating from the Ming era were renovated and traces of their past were obliviated, but here, there had been no grand renovations and thus the village felt genuine. One of the more special remains of the villages past that did survive were the Maoist slogans and cultural revolutionary propaganda painted on the buildings. In almost all other villages, these were removed, but here many of these texts were still visible, like e.g. the ones in the pictures below. China’s red flags added to the atmosphere…

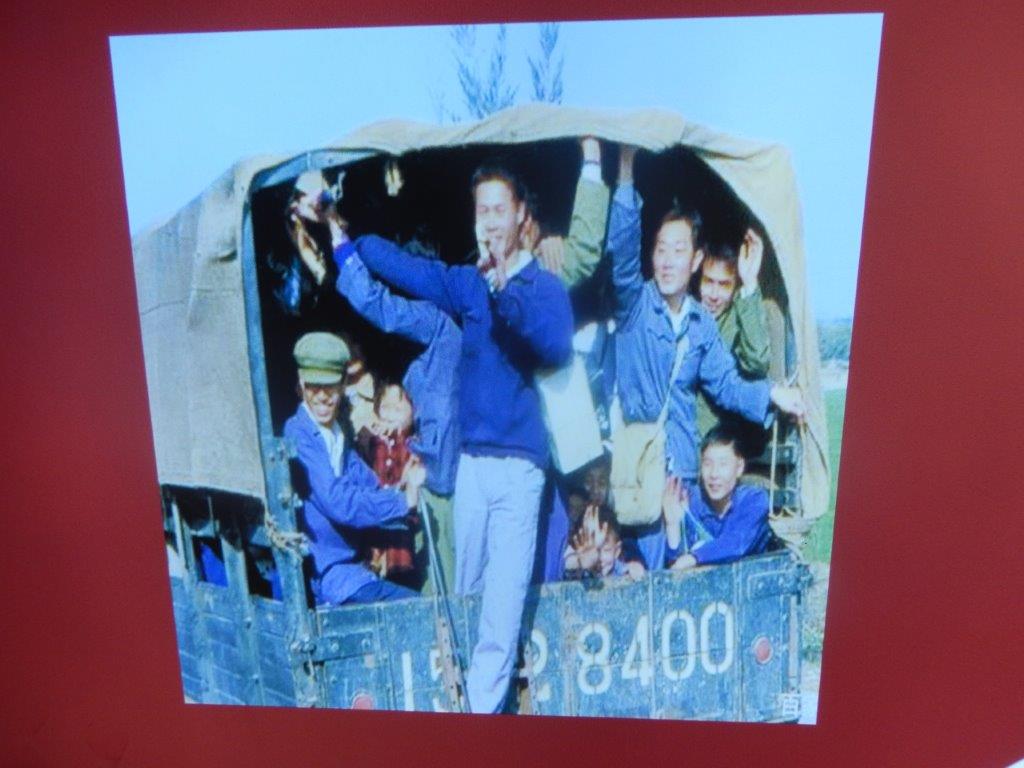

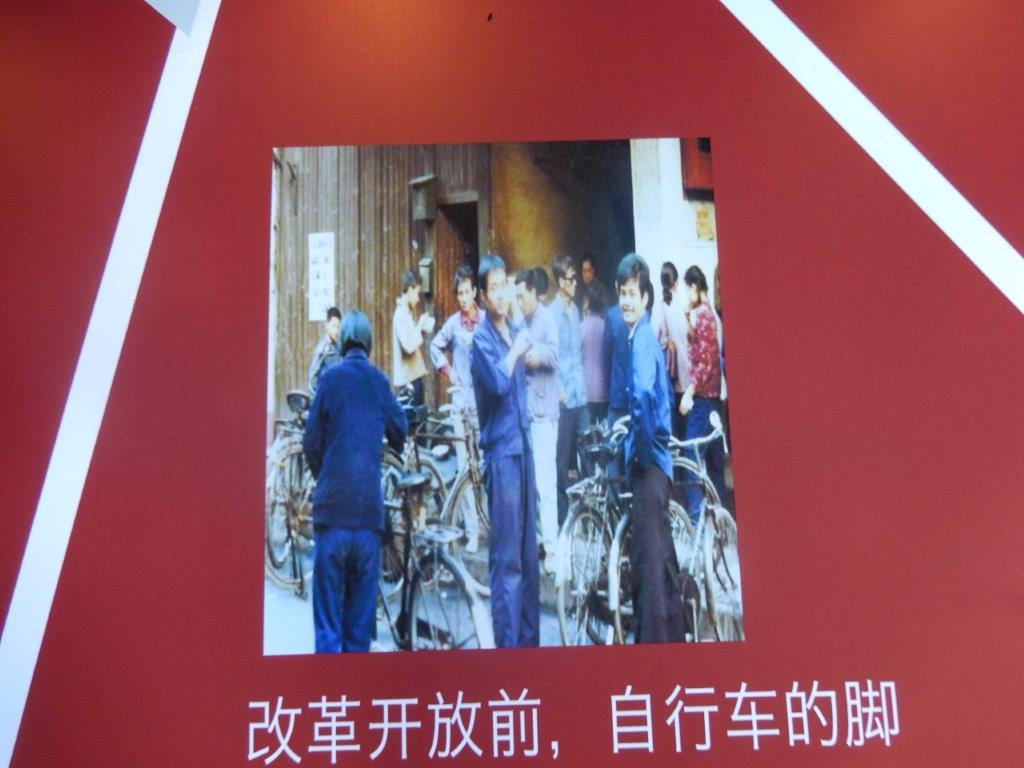

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a sociopolitical movement in China from 1966 until Mao Zedong’s death in 1976. Launched by Mao, the Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and founder of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), its stated goal was to preserve Chinese communism by purging remnants of capitalist and traditional elements from Chinese society, and to re-impose Mao Zedong Thought (known outside China as Maoism) as the dominant ideology in the PRC. The Revolution marked Mao’s return to the central position of power in China after a period of less radical leadership to recover from the failures of the Great Leap Forward, which caused the Great Chinese Famine (1959–61). However, the Revolution failed to achieve its main goals.

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a sociopolitical movement in China from 1966 until Mao Zedong’s death in 1976. Launched by Mao, the Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and founder of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), its stated goal was to preserve Chinese communism by purging remnants of capitalist and traditional elements from Chinese society, and to re-impose Mao Zedong Thought (known outside China as Maoism) as the dominant ideology in the PRC. The Revolution marked Mao’s return to the central position of power in China after a period of less radical leadership to recover from the failures of the Great Leap Forward, which caused the Great Chinese Famine (1959–61). However, the Revolution failed to achieve its main goals.

After Mao had started his Cultural Revolution, it soon had massive effects on the Cinese People’s political thoughts, but also on their behavior in day-to-day-life. The fact that the Cultural Revolution had such massive effects on Chinese society is the result of extensive use of political slogans. In Huang’s view, rhetoric played a central role in rallying both the Party leadership and people at large during the Cultural Revolution. For example, the slogan “to rebel is justified” (造反有理; zàofǎn yǒulǐ) became a unitary theme.

Huang asserts that political slogans were ubiquitous in every aspect of people’s lives, being printed onto everyday items such as bus tickets, cigarette packets, and mirror tables. Workers were supposed to “grasp revolution and promote productions”, while peasants were supposed to raise more pigs because “more pigs means more manure, and more manure means more grain.” Even a casual remark by Mao, “Sweet potato tastes good; I like it” became a slogan everywhere in the countryside.

Below is another old graffiti slogan…

There were also posters, banners and wooden signs with texts…

Political slogans of the time had three sources: Mao, official Party media such as People’s Daily, and the Red Guards. Mao often offered vague, yet powerful directives that led to the factionalization of the Red Guards. These directives could be interpreted to suit personal interests, in turn aiding factions’ goals in being most loyal to Mao Zedong. Red Guard slogans were of the most violent nature, such as “Strike the enemy down on the floor and step on him with a foot”, “Long live the red terror!” and “Those who are against Chairman Mao will have their dog skulls smashed into pieces.”

Mao on a small poster created during his days in power…

Sinologists Lowell Dittmer and Chen Ruoxi point out that the Chinese language had historically been defined by subtlety, delicacy, moderation, and honesty, as well as the “cultivation of a refined and elegant literary style.” This changed during the Cultural Revolution. Since Mao wanted an army of bellicose people in his crusade, rhetoric at the time was reduced to militant and violent vocabulary. These slogans were a powerful and effective method of “thought reform,” mobilizing millions in a concerted attack upon the subjective world, “while at the same time reforming their objective world.”

Dittmer and Chen argue that the emphasis on politics made language a very effective form of propaganda, but “also transformed it into a jargon of stereotypes—pompous, repetitive, and boring.” To distance itself from the era, Deng Xiaoping’s government cut back heavily on the use of political slogans. The practice of sloganeering saw a mild resurgence in the late 1990s under Jiang Zemin.

I had read a lot about these texts and there meaning before visiting Cuandixia.

Some public tools

On a small square amidst of the villages houses, The Wandelgek discovered some tool that looked like a walls, maybe for wheat? It was there out in the open for anyone to use it when neccesary. I think it is quite wise to heve some tools in a village as small as this one, which are available for the whole community…

Not sure what sort of a tool this was (the explanatory sign was in Chinese), but again it looked like it could be utilized by the whole community. It might however be some sort of a well, bacause it definitely did transport water…

The Wandelgek had now reached the middle section of the village and decided to visit some more courtyards and houses in this area to try and see how people must have lived overhere…

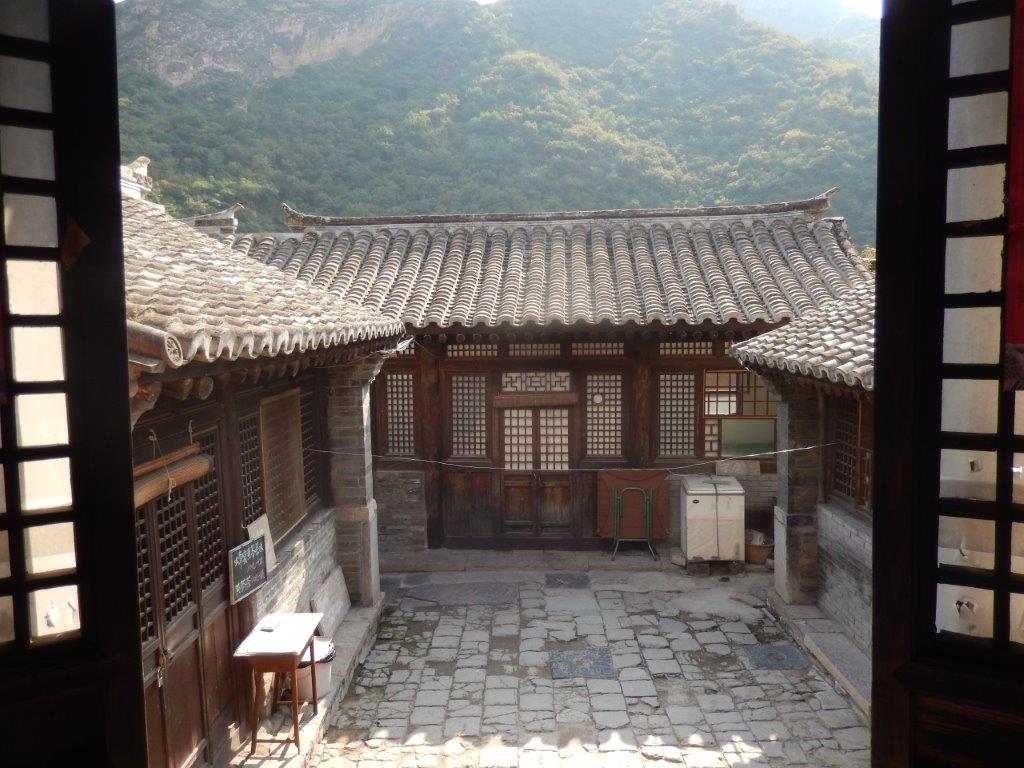

Visiting some Ming dynasty houses

A very beautiful house with courtyard was this one, which reminded The Wandelgek of some Zhang Yimou movies he had seen long ago in an arthouse in The Netherlands. The movies were named: Red Sorghum and Raise the red lantern. The only thing missing were those red lanterns. From the courtyard, The Wandelgek walked towards the main house…

… and entered it.

An exhibition about the Cultural Revolution

The interior of these houses is a bit gloomy. It is not brightly lit, but dependant on the ount of light admitted via wooden doors and window shutters that allow only a fraction of the light putside to enter.

Inside was a small exhibition about life in this village during Mao’s regime and during the Cultural Revolution. What was kept in The Wandelgek’s memory was that the philosophy of Maoistic communism, meant that people not only earned approximately the same and could buy approximately the same products, but that they also wore identical clothes, almost like uniforms…

The Wandelgek left the house and the courtyard and via small alleys he walled towards the next courtyard…

Raise the Red Lantern

There was an abbundance of red lanterns in this awesome courtyard and the main house was open for visitors….

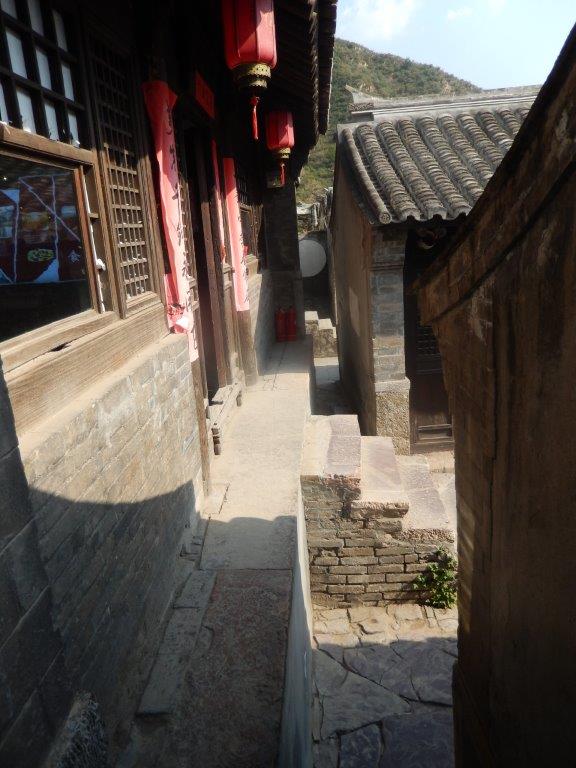

But 1st the courtyard and the little alleys that connected it with the outside world. This courtyard and house were a really good example of the atmosphere of buildings shown in those movies, although the buildings in the movies were owned by a bit more rich Chinese men, there were also a lot of similarities with these more humble buildings in Cuandixia…

Raise the Red Lantern is a 1991 film directed by Zhang Yimou and starring Gong Li. It is an adaptation by Ni Zhen of the 1990 novel Wives and Concubines by Su Tong. The film was later adapted into an acclaimed ballet of the same title by the National Ballet of China, also directed by Zhang.

Set in the 1920s, the film tells the story of a young woman who becomes one of the concubines of a wealthy man during the Warlord Era. It is noted for its opulent visuals and sumptuous use of colours. The film was shot in the Qiao Family Compound near the ancient city of Pingyao, in Shanxi Province. Although the screenplay was approved by Chinese censors, the final version of the film was banned in China for a period.

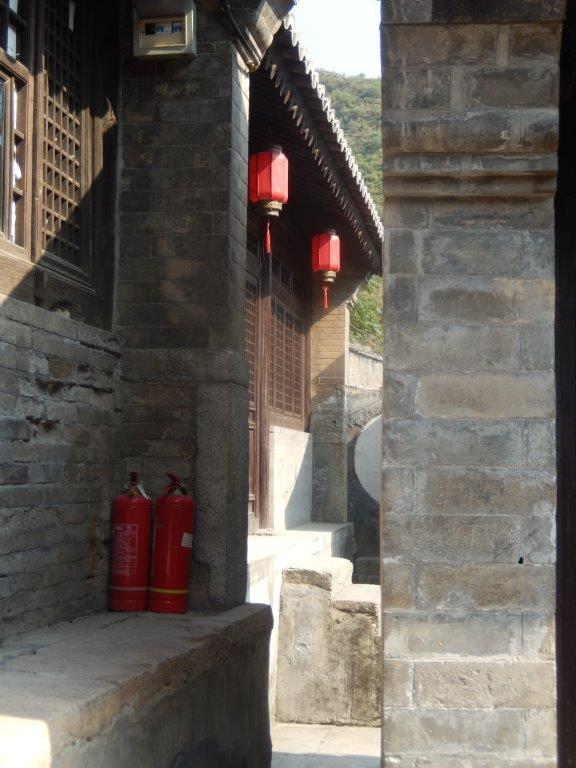

Fire extinguishers were positioned in strategic places, a bit out of sight. All buildings are priceless in cultural historical sense and because they were partly made of wood, this was not a very bad idea…

How are traditional Ming villages structured?

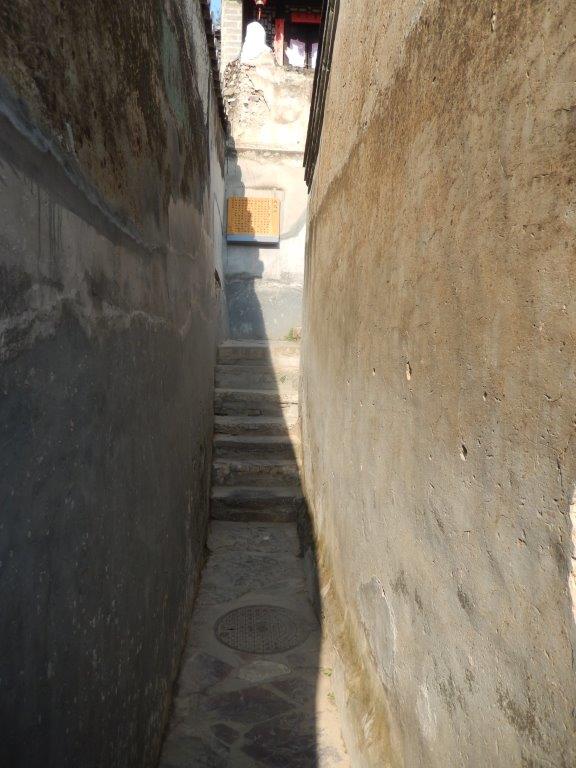

Typical for villages that were build during the Ming dynasty, is that houses were almost connected to eachother. There were no streets in between except very small alleys and of course there were many secluded courtyards, bordered by walls and buildings, like shown in the pics below…

A traditional Ming house (Dawujian) interior

In a rural area it was not uncommon for people to hang achricultural products outside of their houses, like the corn underneath the roof in the pic below…

The wooden windows are covered with a white rice paper which didn’t allow passers by to look in, but did allow the owners to look out…

The Wandelgek 1st entered the Tangwu (Living room) of the Dawujian house which had 5 large rooms underneath its roof…

The Tangwu

The Tangwu

Tangwu is a Mandarin Chinese word, meaning the central room of a traditional Chinese house.

In this beautiful tangwu, with a beautiful wooden beam ceiling, were two chairs, one on both sides of a set of two tables placed exaclty in the rooms center, in front of the main entrance door, but placed against the opposite wall…

The room was lit by a couple of lanterns and there were also two sets of chests, placed against the opposite wall, one set on both sides of the table and chair ensemble. Above the tables was a framed painting and on each side of it was a framed text. It all gave the impression of symmetry. Wooden pillars supported the ceiling. Blue Ming china vases were decorating the room as well.

There were two smaller side rooms as well, one on each side of the tangwu. In the picture below, The Wandelgek is standing in a side room, looking into the central room and towards the other side room…

Cellar

The houses around a quadrangle or courtyard were all belonging to one owner and per quadrangle there was a cellar available to store goods.

Ming china vases? I’m not knowledgeable concerning Ming china porcelain, and I’m in real doubt tgat tgere will be real Ming china vases exhibited like this in an unguarded public space, apart from that the vase on the left looks to light blue for being a Ming china vase. Porcelain is only one of many different types of pottery but it is usually valued more than others because of the smoothness of its surface, its pure whiteness, and its translucent quality. Markings run ussually from top to bottom which is beliefed to be originating from ancient calligraphers that wrote vertically on pieces of bone or bamboo. A Ming porcelain vase or cup can nowadays be auctuined for prices between $300,000 and $500,000.

The windows all had intricate structures of wood carvings in them…

Even in those ancient days, humans were already utilizing and taking care of Cats and dogs…

The Wandelgek was very pleased with his visit to this beautiful quadrangle style Ming dynasty house in Cuandixia. It looked wonderfully well preserved and felt really old…

He now moved on to see some other buildings in the village, like e.g this house that he found, strolling through some narrow alleys, in another quadrangle…

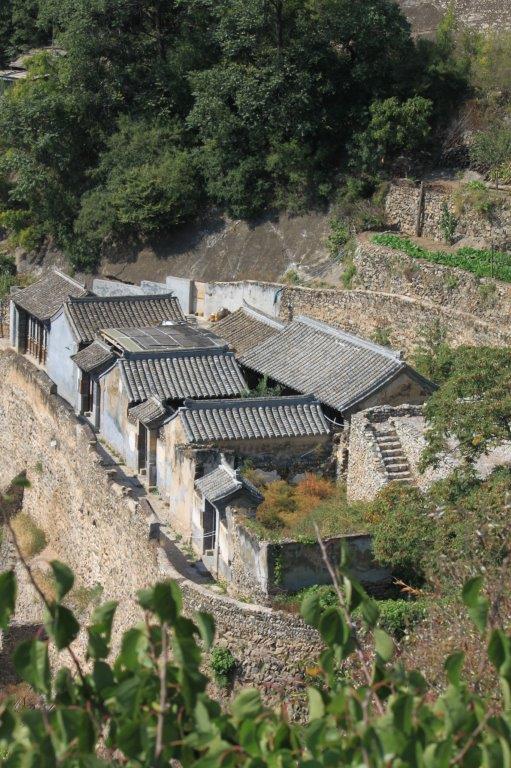

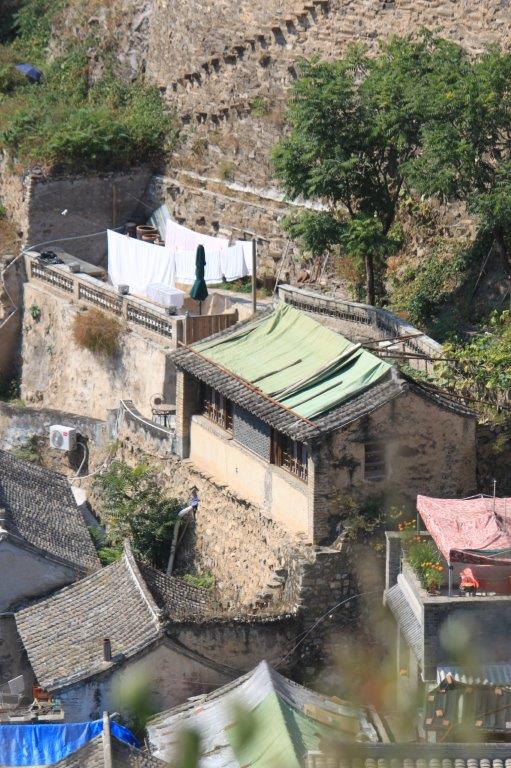

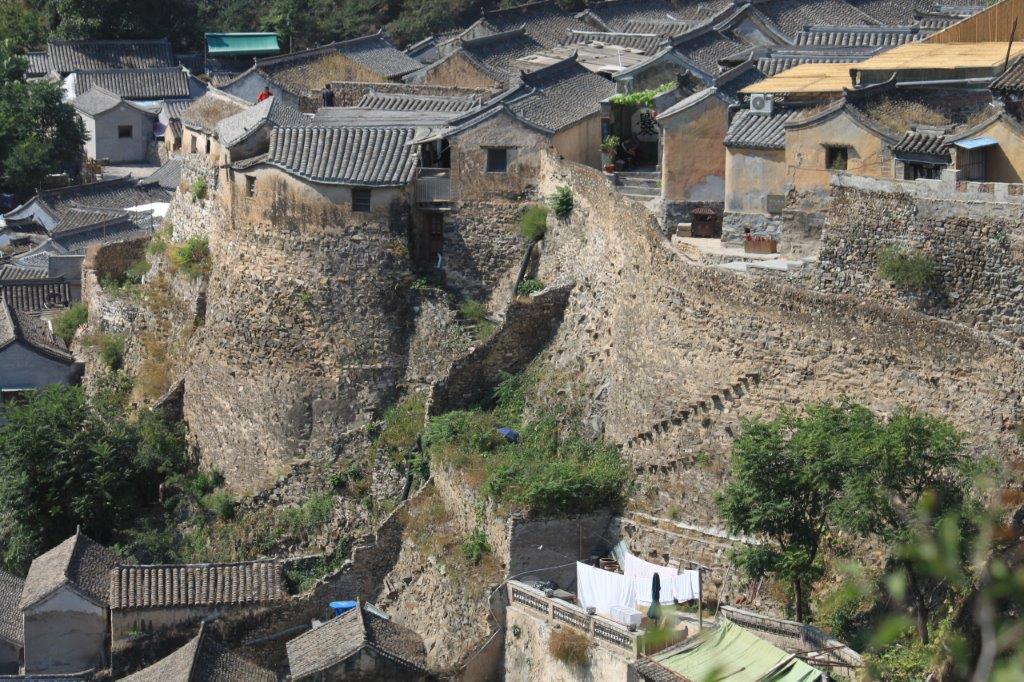

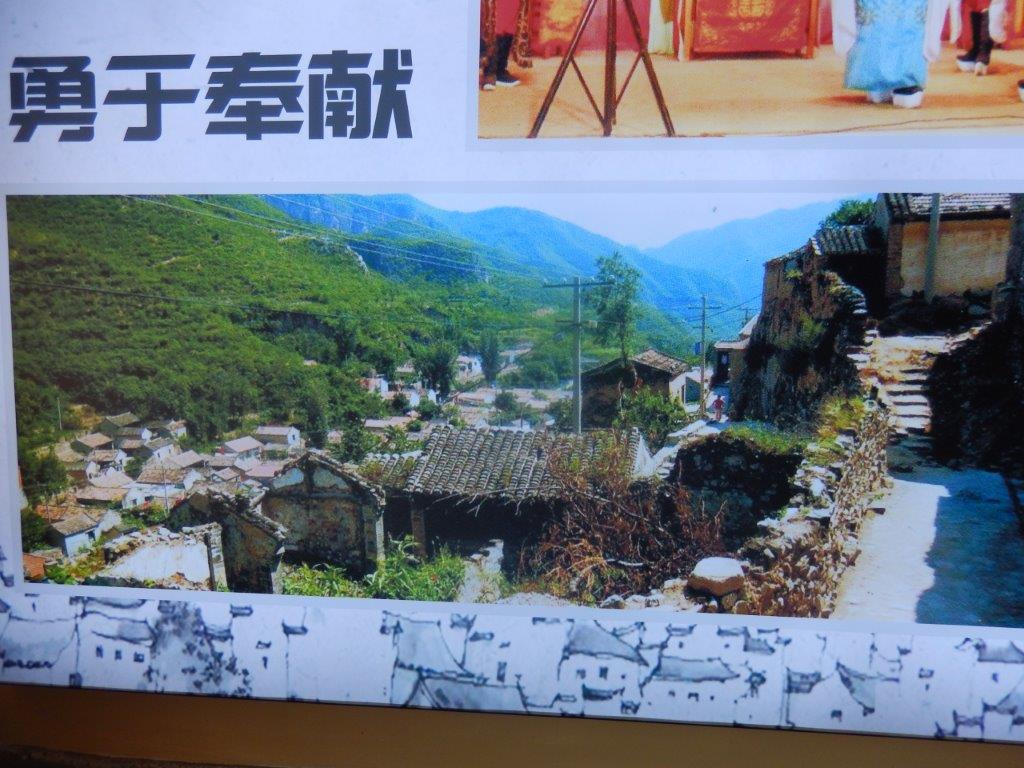

How did they built a village against such a steep slope?

In the pictures below it becomes more clear how a village like Cuandixia wa built angainst a steep mountain slope…

As I see it, they used a system not unsimilar to the ricefields on the steep slopes of south east asia’s Vietnam, Java and Bali.

In these countries people built flat terraces that are surrounded by little dirt walls (dykes) which contain water. Within these walls rice plants can grow…

In Cuandixia however, those dirt walls were strengthened with bricks or stones…

On top, the floor was equalized/flattened/ horizontalized. This created a space to build houses. These houses are build in an area with lack of space and are almost bordering eachother. Only very narrow alleys are allowed in between so inhabitants could move around. These alleys often had stairs too, making it possible to ascend and descend from one step to a higher or lower step on the slope…

This created the typical structure and view of this beautiful rural Ming dynasty mountain village…

Wudao: A small village temple

The village did not solely consist of houses, although the majority of the buildings were. Beneath is an example of the interior of a small temple where villages honored and registered their deceased…

The picture below was from the temple entrance…

A statue of Wudaoye ( Grandfather Wudao) was placed on a small altar where villagers could leave offerings which would help their deceased relatives to gain access to the afterworld…

Chinese folk religion, also known as Chinese popular religion, is a general term covering a range of traditional religious practices of Han Chinese, including the Chinese diaspora. Vivienne Wee described it as “an empty bowl, which can variously be filled with the contents of institutionalised religions such as Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, the Chinese syncretic religions”. This includes the veneration of shen (spirits) and ancestors, exorcism of demonic forces, and a belief in the rational order of nature, balance in the universe and reality that can be influenced by human beings and their rulers, as well as spirits and gods. Worship is devoted to gods and immortals, who can be deities of places or natural phenomena, of human behaviour, or founders of family lineages. Stories of these gods are collected into the body of Chinese mythology. By the Song dynasty (960-1279), these practices had been blended with Buddhist doctrines and Taoist teachings to form the popular religious system which has lasted in many ways until the present day. The present day government of mainland China, like the imperial dynasties, tolerates popular religious organizations if they bolster social stability but suppresses or persecutes those that they fear would undermine it.

Modern influences

The village was nowadays prepared for living in modern China. There was e.g. electricity and in several locations, The Wandelgek spotted these outdoor fuse boxes…

Another outdoor set of fuse boxes and some fire extinguishers right next to it. Safety 1st …

Buildings like this one below are not only for living, but could have a function for future tourism too. Travellers and tourists need places to stay the night and these locations are in such a beautiful environment where history and nature mingle…

Obviously tourism was also a contributor for some adaptions to the village, like e.g. these shade providing roofs, where tourists or travellers could rest and eat and drink.

And then there were parts of the village where new modern houses were started to get built. It made The Wandelgek wonder for how long this village, that had been isolated for such a long time in history, would still keep its unspoiled character …

These blue motorized vehicles were used to carry heavy piles of bricks through the narrow, ascending streets, towards and from building locations to the old post road which had been transformed fairly recently into a broad main street down in the valley …

From there the building materials could be reloaded from or onto a normal truck…

Clearly the modern age had finally arrived in Cuandixia…

My next upcoming blogpost about China will be about a walk into the surrounding mountains…