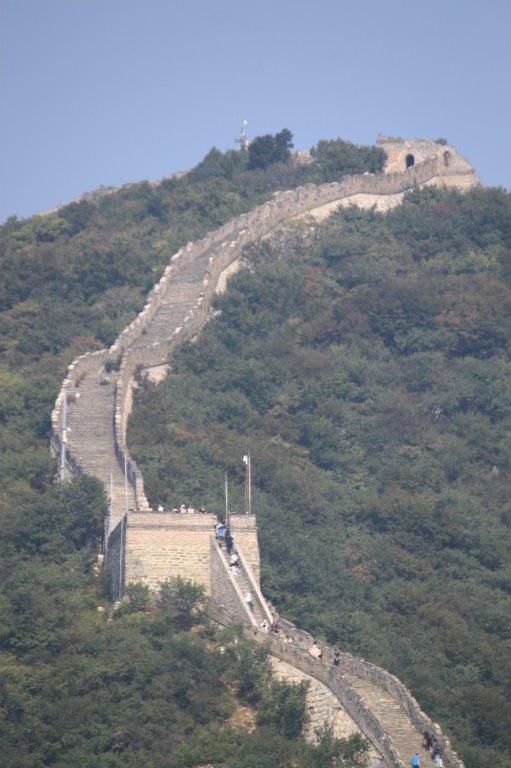

Defense against the Mongols: The Chinese Wall at Mutianyu

Solo travel in Greater Beijing

After an early breakfast (at which The Wandelgek said goodbye to his fellow travellers on the Trans Siberian Express, which had a flight back home that morning), The Wandelgek had some days of solo travel planned through Great Beijing.

The Wandelgek had arranged for a cab and driver to be available all day which was possible for around 1000 remnin (yuan) (= 128 Euro). Quite a lot actually, but cabs are the most expensive transport in Beijing and The Wandelgek had planned to visit 2 sites, of which the wall was planned in the morning. It is not that easy to visit 2 sites outside of Beijing on 1 day, by the much cheaper public transport, because to do so you need to return to the city center and go from there to the 2nd location. That costs a lot of time in a city as large as Beijing. So The Wandelgek chose to spend the money. The Wandelgek also noticed that cab drivers do not wait for you to return from a visit, but they try to do some other drives with customers during your visit. You can either call them when you need them or agree upon a time when they need to be present.

7 World Wonders?

Today The Wandelgek was going to visit one of the World Wonders created by humanity. If we go back in history to the Classic history of the Egyptians, the Greek and the Romans, there is this list of 7 World Wonders, including:

- The Pyramids of Gizeh,

- The Walls of Babylon,

- The Gardens of Semiramis,

- The Olympic Zeus Statue of Phidias,

- The Mausoleum of Halicarnassus,

- The Temple of Artemis in Efeze &

- The Colossus of Rhodos.

But from that Classic time there was already a surrogate wonder added to that list. That was The Pharos of Alexandria (a lighthouse).

Mankind has evolved much further since those days and I think there are several newer wonders that could be added to that list, of which one is beyond any doubt the Great Wall of China.

The Wandelgek had been in doubt about which section of the Great Wall to visit: Badaling, Mutianyu or Simatai?

After some discussions with fellow travelers during the many hours spend on the train, he had a preference for Simatai, which was not touristic because the wall was in a deplorable but still original, unspoiled state. But it was the furthest location from central Beijing and thus quite expensive to get there by cab. Too expensive in the end.

The Wandelgek now had to choose between the 1st site ever of the wall, accessible for tourists at Badaling, which was a very touristic and commercially exploited location and the more recently opened site at Mutianyu. From travellers on the train who had been there years ago, he learned it had been much less commercially exploited back then, meaning there were no or less shops selling souvenirs and tourists were less hassled into buying souvenirs.

The Wandelgek chose to visit Mutianyu, but time had passed and although there were no hasseling sellers of souvenirs, there was a complete street full of souvenir shops and little restaurants between the busparking and the cable car lift.

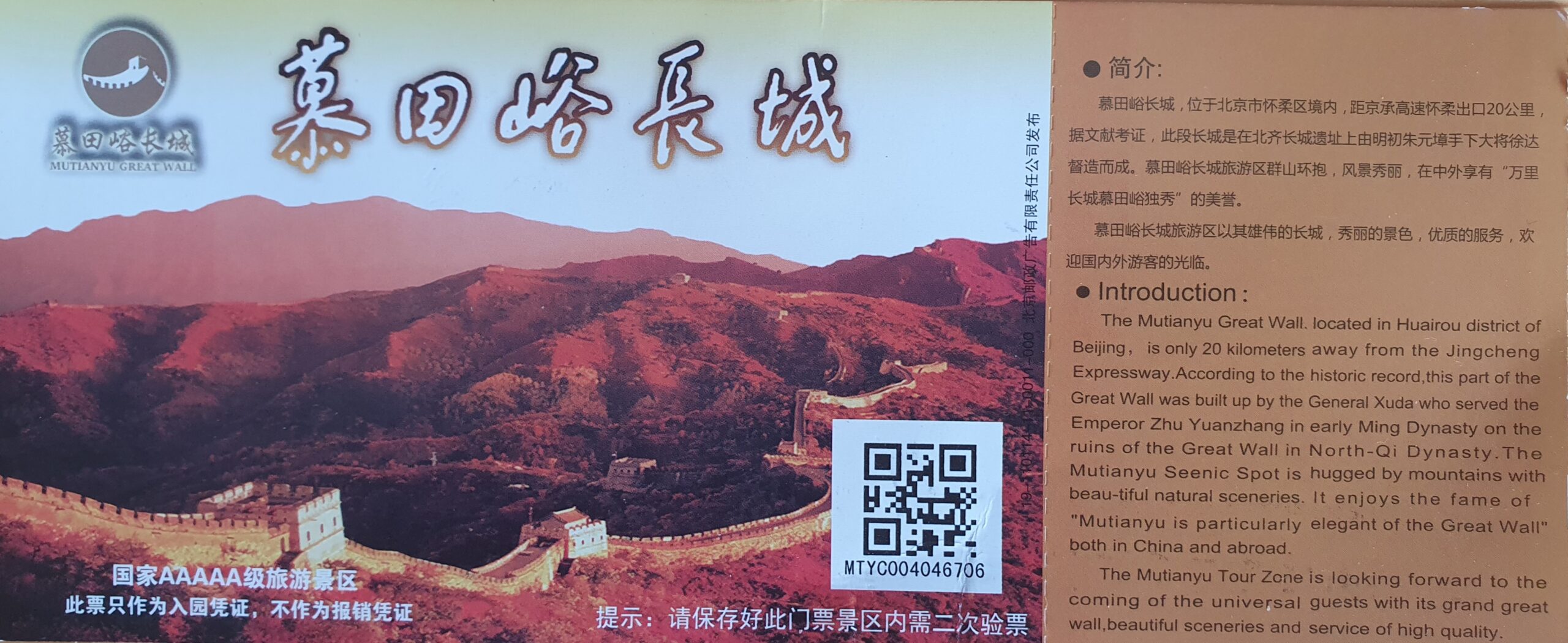

To reach the Great Wall of China at Mutianyu, you can buy a busticket towards the cable car lift, a cable car lift ticket and an entrance ticket per section of the wall you want to visit. At Mutianyu it is possible to travel up in another cabin lift than down. But to do this you need to visit 2 wall sections.

The Wandelgek visited 1 section of the wall:

- Bus ticket: 15 Rmb (=1.90 Euro)

- Cable car lift ticket: 120 Rmb (=15.40 Euro)

- Wall section ticket: 40 Rmb (=5.10 Euro)

The Wandelgek took the cabin lift up to the wall, which is built upon a mountain ridge far above…

The cabins were mostly empty yet because it was still early morning…

…and the cabins were ascending on the steep tree covered slopes

…until The Wandelgek suddenly had his 1st view on the Chinese Wall.

Almost on top just underneath the wall was the cabin lift station and a bit further up was a small coffee corner where The Wandelgek enjoyed a cup of coffee looking up towards the wall.

From there it was a steep stair up towards the top of …

The Great Wall of China

The Great Wall of China is a series of fortifications that were built across the historical northern borders of ancient Chinese states and Imperial China as protection against various nomadic groups from the Eurasian Steppe. Several walls were built from as early as the 7th century BC, with selective stretches later joined together by Qin Shi Huang (220–206 BC), the first emperor of China. Little of the Qin wall remains. Later on, many successive dynasties built and maintained multiple stretches of border walls. The best-known sections of the wall were built by the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

After his roadtrip through northern an central Mongolia and his travels on the Trans Mongolian Railway, The Wandelgek was now standing on top of a manmade construction, which was built to keep the invading Mongol tribes north of the wall.

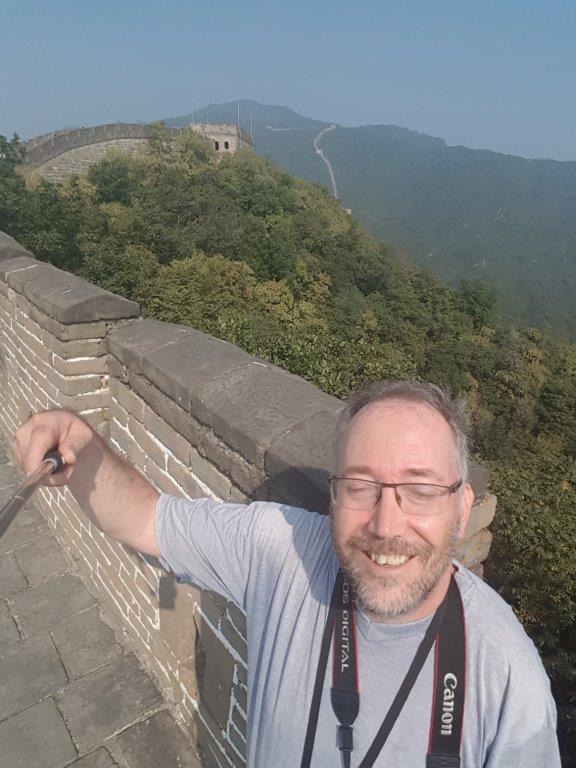

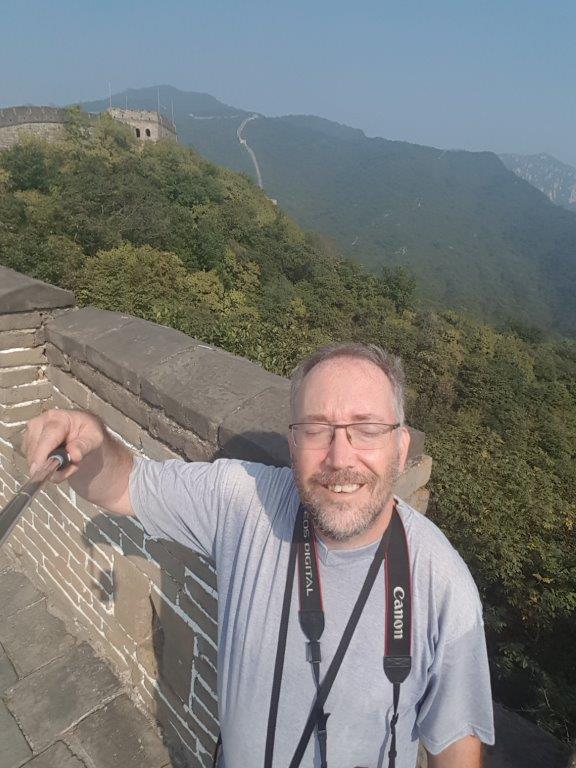

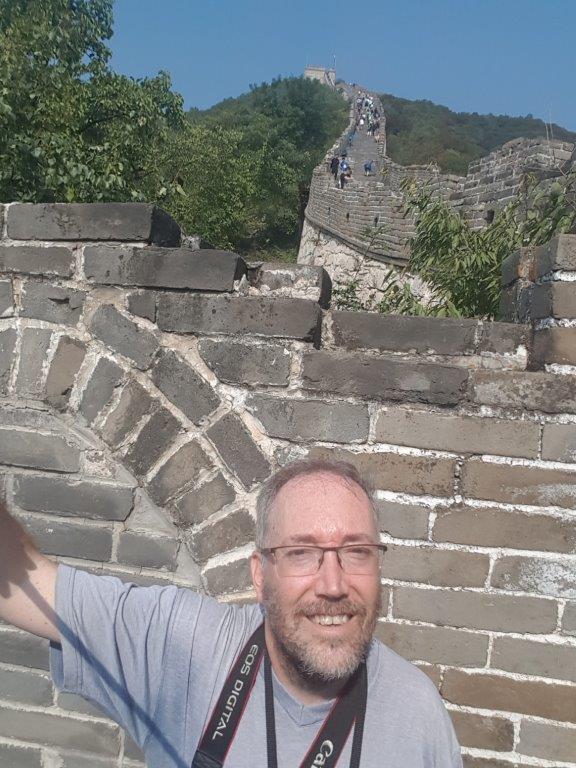

My 1st pic on top of the Great Wall of China:

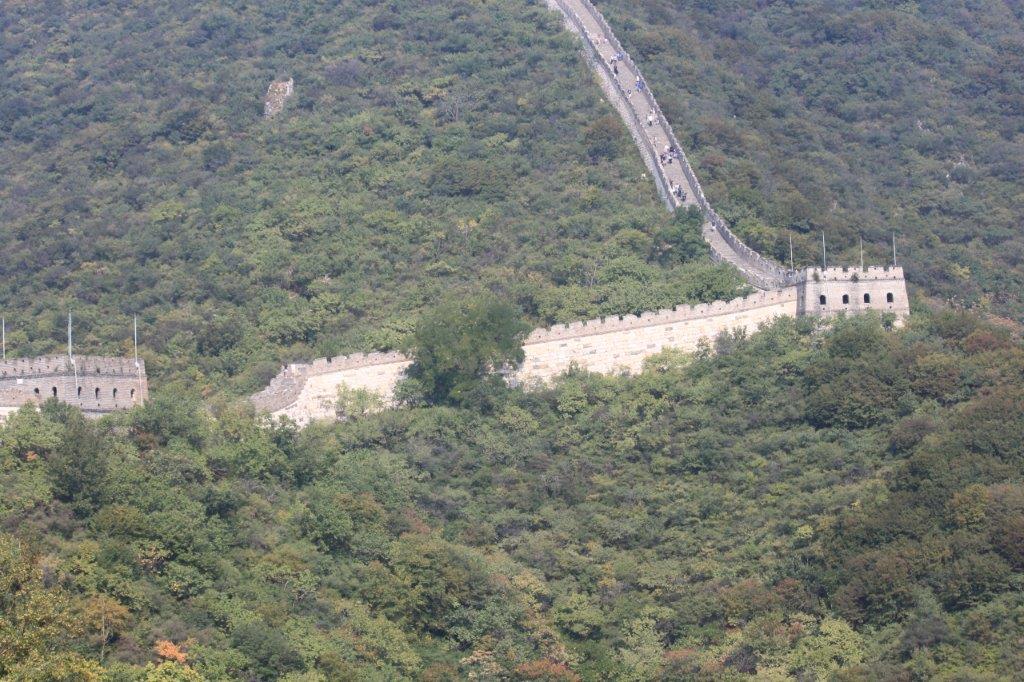

On top of the wall were lots of watch towers…

Apart from defense, other purposes of the Great Wall have included border controls, allowing the imposition of duties on goods transported along the Silk Road, regulation or encouragement of trade and the control of immigration and emigration. Furthermore, the defensive characteristics of the Great Wall were enhanced by the construction of watchtowers, troop barracks, garrison stations, signaling capabilities through the means of smoke or fire, and the fact that the path of the Great Wall also served as a transportation corridor.

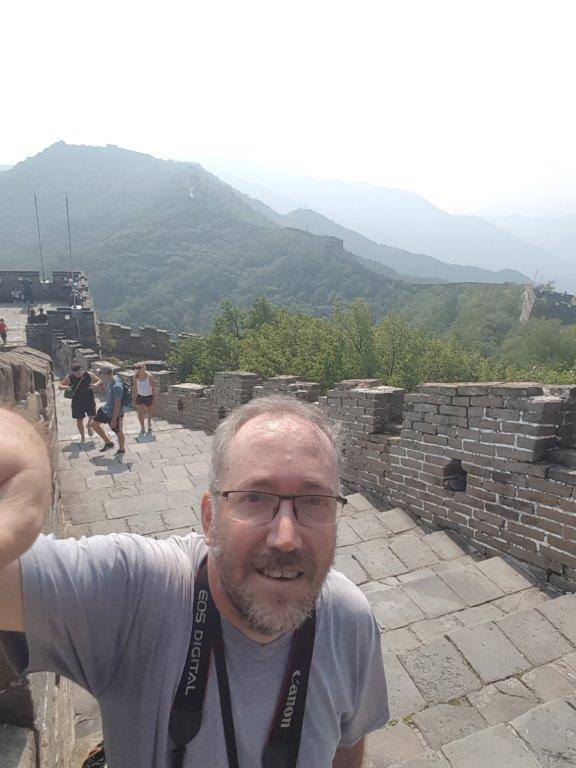

It was getting warmer and warmer as the sun rose and also quite difficult to make an acceptable photo selfie loiking staight into the sun…

Bloopers

Early walls

The Chinese were already familiar with the techniques of wall-building by the time of the Spring and Autumn period between the 8th and 5th centuries BC. During this time and the subsequent Warrig States period, the states of Qin, Wei, Zhao, Qi, Han, Yan, and Zhongshan all constructed extensive fortifications to defend their own borders. Built to withstand the attack of small arms such as swords and spears, these walls were made mostly of stone or by stamping earth and gravel between board frames.

King Zheng of Qin conquered the last of his opponents and unified China as the First Emperor of the Qin dynasty (“Qin Shi Huang”) in 221 BC. Intending to impose centralized rule and prevent the resurgence of feudal lords, he ordered the destruction of the sections of the walls that divided his empire among the former states. To position the empire against the Xiongnu people from the north, however, he ordered the building of new walls to connect the remaining fortifications along the empire’s northern frontier. “Build and move on” was a central guiding principle in constructing the wall, implying that the Chinese were not erecting a permanently fixed border. Transporting the large quantity of materials required for construction was difficult, so builders always tried to use local resources. Stones from the mountains were used over mountain ranges, while rammed earth was used for construction in the plains. There are no surviving historical records indicating the exact length and course of the Qin walls. Most of the ancient walls have eroded away over the centuries, and very few sections remain today.

The human cost of the construction is unknown, but it has been estimated by some authors that hundreds of thousands workers died building the Qin wall. Later, the Han, the Northern dynasties and the Sui all repaired, rebuilt, or expanded sections of the Great Wall at great cost to defend themselves against northern invaders. The Tang and Song dynasties did not undertake any significant effort in the region. Dynasties founded by non-Han ethnic groups also built their border walls: the Xianbei-ruled Northern Wei, the Khitan-ruled Liao, Jurchen-led Jin and the Tangut-established Western Xia, who ruled vast territories over Northern China throughout centuries, all constructed defensive walls but those were located much to the north of the other Great Walls as we know it, within China’s autonomous region of Inner Mongolia and in modern-day Mongolia itself.

Ming era (1368-1644)

The Great Wall concept was revived again under the Ming in the 14th century, and following the Ming army’s defeat by the Oirats in the Battle of Tumu. The Ming had failed to gain a clear upper hand over the Mongol tribes after successive battles, and the long-drawn conflict was taking a toll on the empire. The Ming adopted a new strategy to keep the nomadic tribes out by constructing walls along the northern border of China. Acknowledging the Mongol control established in the Ordos Desert, the wall followed the desert’s southern edge instead of incorporating the bend of the Yellow River.

Unlike the earlier fortifications, the Ming construction was stronger and more elaborate due to the use of bricks and stone instead of rammed earth. Up to 25,000 watchtowers are estimated to have been constructed on the wall. As Mongol raids continued periodically over the years, the Ming devoted considerable resources to repair and reinforce the walls. Sections near the Ming capital of Beijing were especially strong. Qi Jiguang between 1567 and 1570 also repaired and reinforced the wall, faced sections of the ram-earth wall with bricks and constructed 1,200 watchtowers from Shanhaiguan Pass to Changping to warn of approaching Mongol raiders. During the 1440s–1460s, the Ming also built a so-called “Liaodong Wall”. Similar in function to the Great Wall (whose extension, in a sense, it was), but more basic in construction, the Liaodong Wall enclosed the agricultural heartland of the Liaodong province, protecting it against potential incursions by Jurchen-Mongol Oriyanghan from the northwest and the Jianzhou Jurchens from the north. While stones and tiles were used in some parts of the Liaodong Wall, most of it was in fact simply an earth dike with moats on both sides.

Towards the end of the Ming, the Great Wall helped defend the empire against the Manchu invasions that began around 1600. Even after the loss of all of Liaodong, the Ming army held the heavily fortified Shanhai Pass, preventing the Manchus from conquering the Chinese heartland. The Manchus were finally able to cross the Great Wall in 1644, after Beijing had already fallen to Li Zicheng’s short-lived Shun dynasty. Before this time, the Manchus had crossed the Great Wall multiple times to raid, but this time it was for conquest. The gates at Shanhai Pass were opened on May 25 by the commanding Ming general, Wu Sangui, who formed an alliance with the Manchus, hoping to use the Manchus to expel the rebels from Beijing. The Manchus quickly seized Beijing, and eventually defeated both the Shun dynasty and the remaining Ming resistance, consolidating the rule of the Qing dynasty over all of China proper.

Under Qing rule, China’s borders extended beyond the walls and Mongolia was annexed into the empire, so constructions on the Great Wall were discontinued. On the other hand, the so-called Willow Palisade, following a line similar to that of the Ming Liaodong Wall, was constructed by the Qing rulers in Manchuria. Its purpose, however, was not defense but rather to prevent Han Chinese migration into Manchuria.

Conclusion: So there you have it. Many small states got invaded several times by nomadic tribes from the north and seperately started to built defensive walls. But to face this strong enemy, these states unified, either because they were conquered or because they saw the necessity of it and then under one ruler, the walls got merged into one large wall too. Nonetheless the wall was not a very effective means of defense because the Mongols broke throgh its defenses in the 13th century and the Manchus did that again in the 17th century. Both invasions led to long occupations of China by foreign powers.

Some statistics about the Great Wall

The defensive lines contain multiple stretches of ramparts, trenches and ditches, as well as individual fortresses.

In 2012, based on existing research and the results of a comprehensive mapping survey, the National Cultural Heritage Administration of China concluded that the remaining Great Wall associated sites include 10,051 wall sections, 1,764 ramparts or trenches, 29,510 individual buildings, and 2,211 fortifications or passes, with the walls and trenches spanning a total length of 21,196.18 km (13,170.70 mi)😳. WOW.

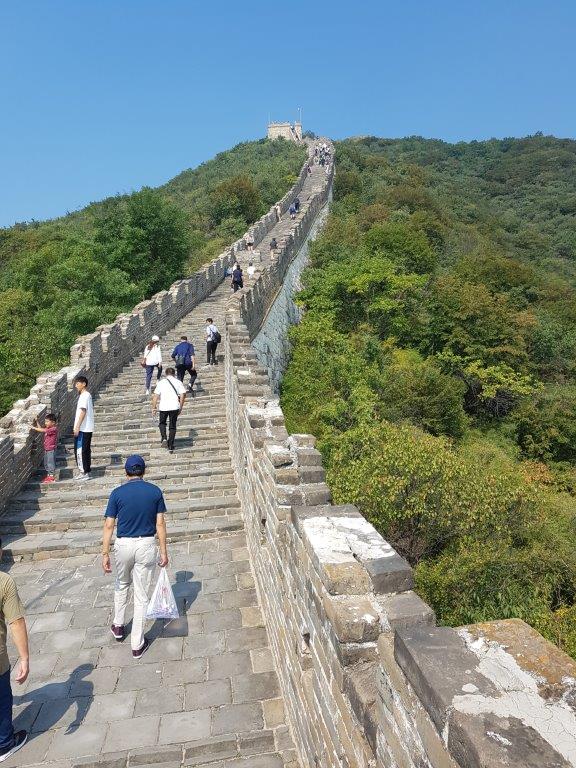

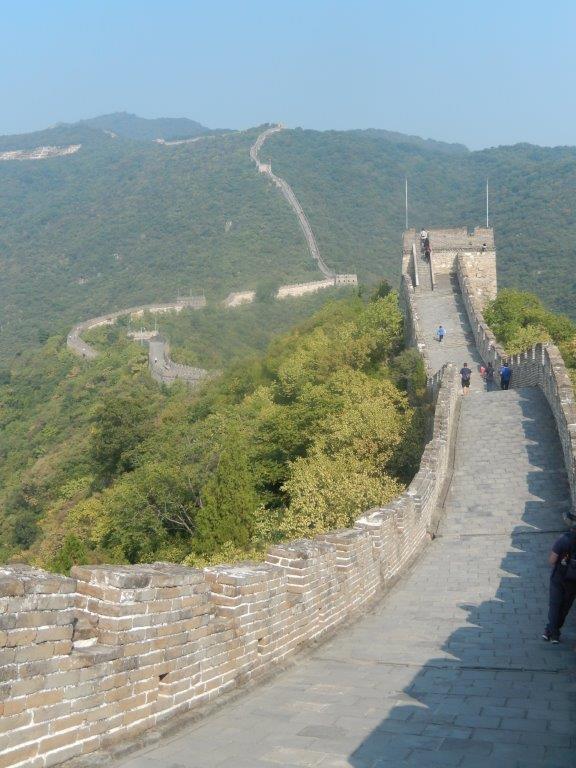

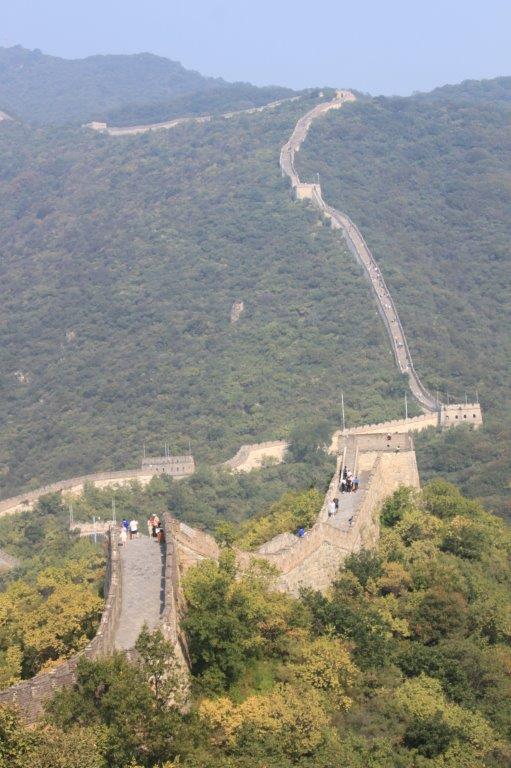

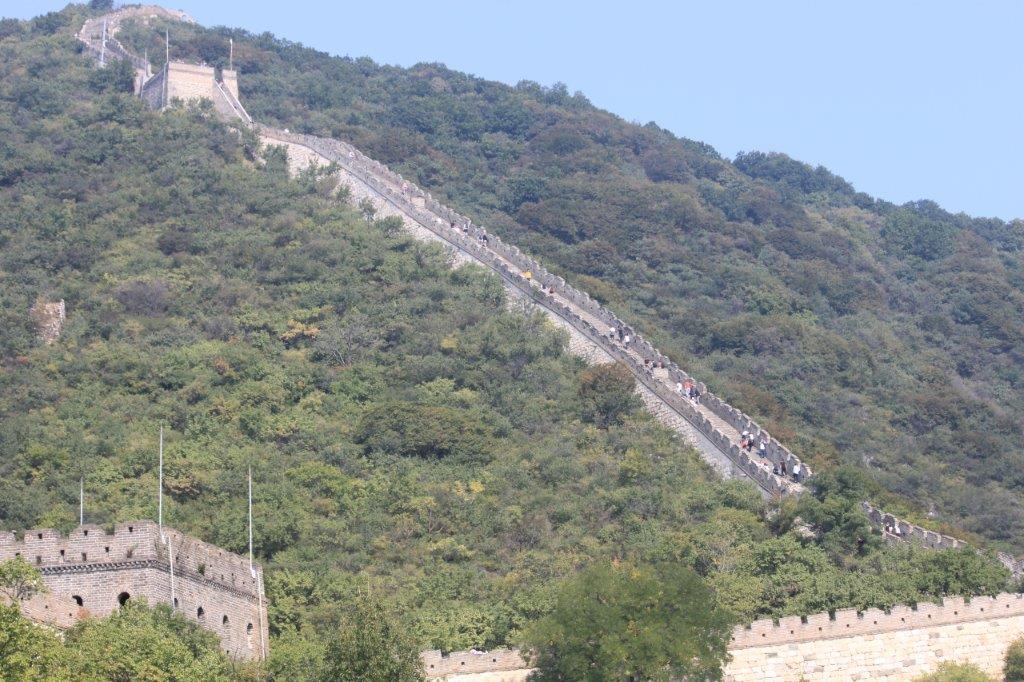

The Wandelgek was now walking uphill and downhill accross the wall, following its many stairs. The wall around Beijing is divided into several sections and a ticket gives you the right to visit a specific section which in this case was the Mutianyu section. It was also possible to buy a bit more expensive ticket which gave access to the next section, from which there is a cable car going down to Mutianyu as well.

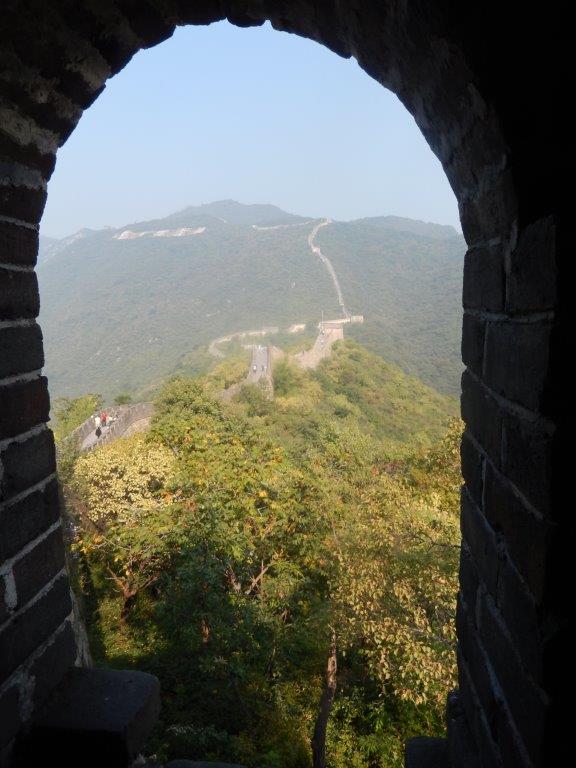

In the last part of the Mutianyu section, the wall was ascending upon a steep hill on, top of which was a watch tower, from where the views over the surrounding landscape were astounding…

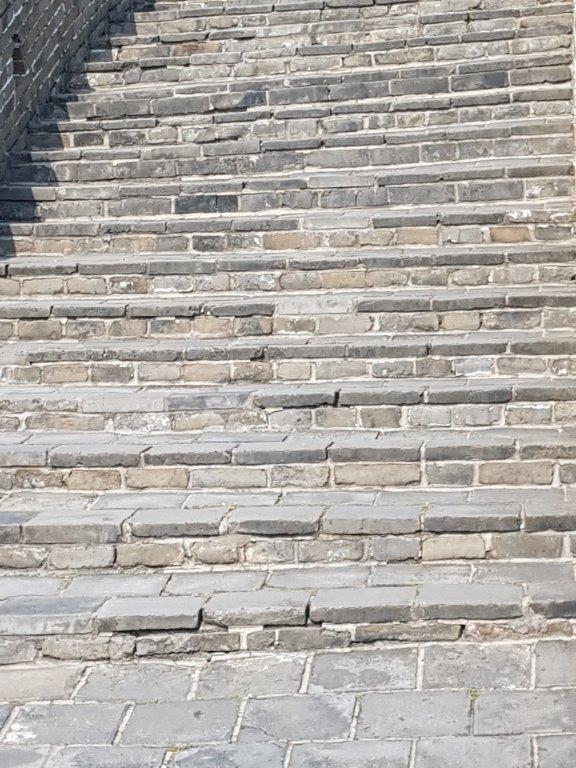

How did they build this????

After a 1st view upon a wall section like this, the 1st thing that pops into mind is: How did they ever do this?

I mean those walls are huge they are on top of a hills and on hill ridges, created from brick shaped stones on the outside and stone rubble inside as its core.

It is a bit similar as these stone walls that I found in The Cotswolds in southern England:

The picture above was taken from a view point just underneath the base of the Great Wall. Locations like this can be found all along the wall and were used to light a fire when the wall was under attack, to warn other watch towers to send soldiers. Different ways of fast communication that were possible because of the wall were smoke, drums and bells. Troops could be moved relatively quicly on top of the wall. Reminded me a bit of this scene from The Lord of the Rings…

From the parapets, guards could survey the surrounding land. Communication between the army units along the length of the Great Wall, including the ability to call reinforcements and warn garrisons of enemy movements, was of high importance. Signal towers were built upon hill tops or other high points along the wall for their visibility. Wooden gates could be used as a trap against those going through. Barracks, stables, and armories were built near the wall’s inner surface.

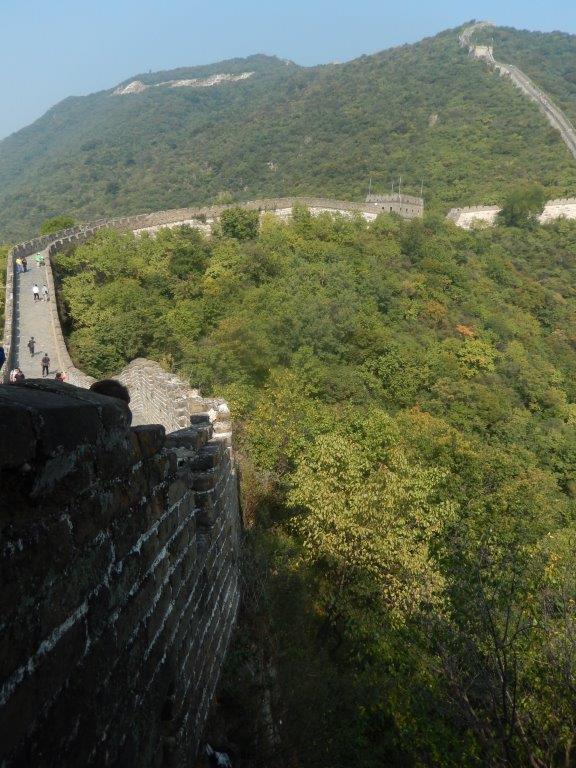

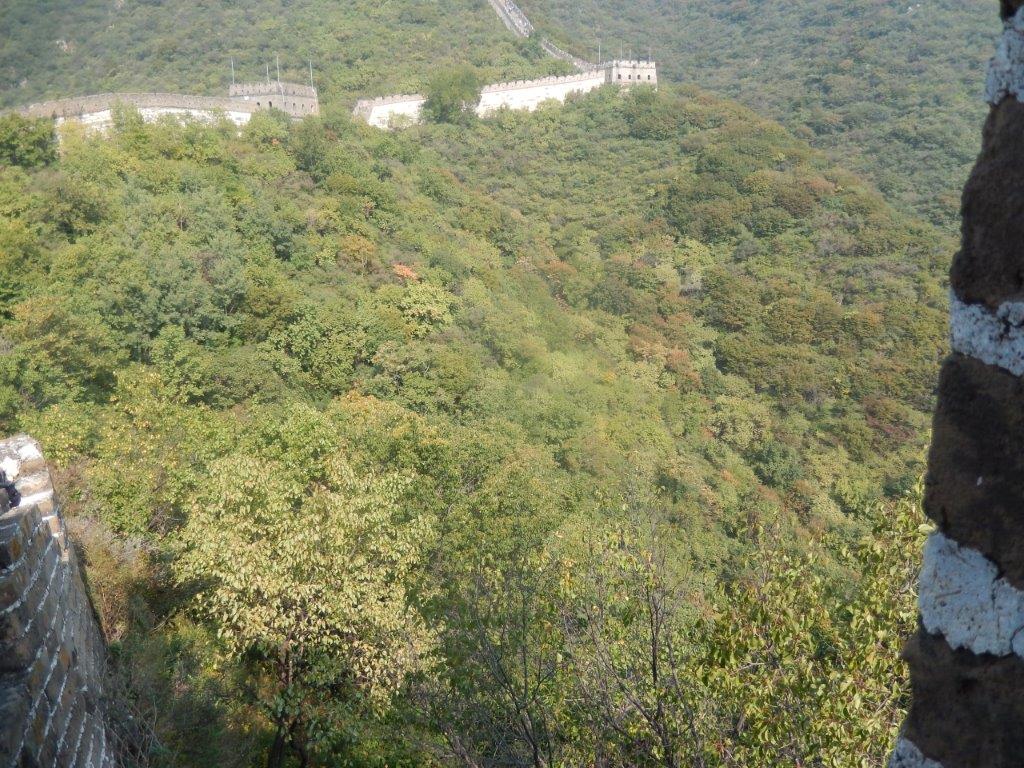

Beneath are views over the difficult landscape where the wall was built.

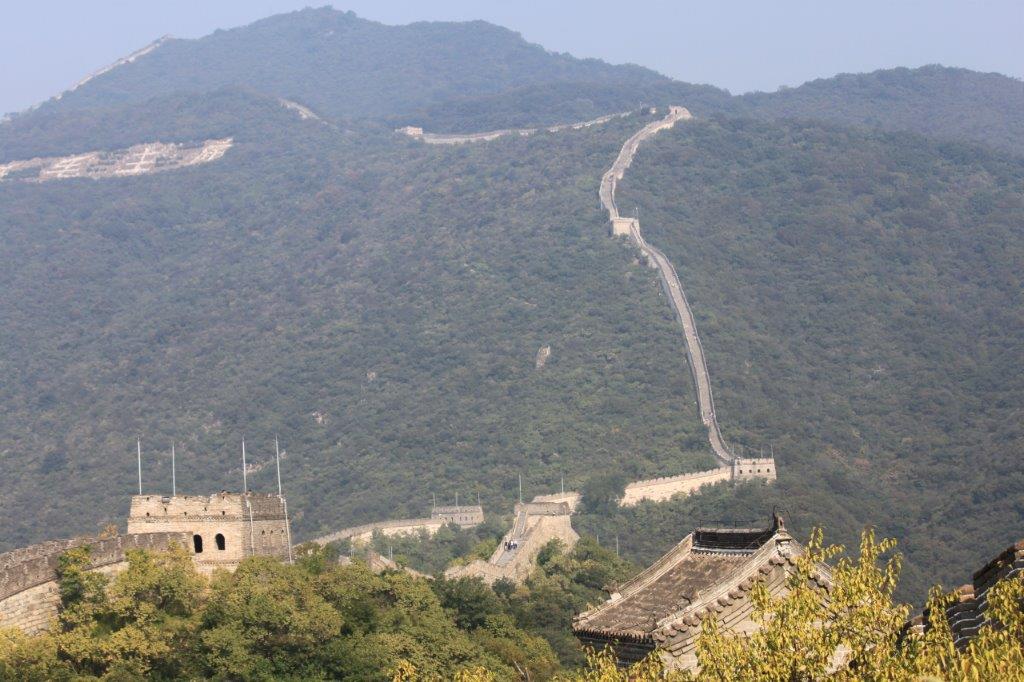

This is a watch tower…

Watch towers added in the Ming era, were built at a distance of two arrowshots from eachother. That made it possible for bowsmen to cover the area in between with their bows and arrows. The towers were multifunctional in use. They were used as fortifications, living quarters for the soldiers and storage area for food and weaponry.

The top of the great wall where people walk is quite wide and thus could be used to move troops quickly or to travel from one end of China to another. The “road” on top has an average width of 7 meters and has an average height of 8 meters (above the hill).

Views from a watchtower. I was experimenting a bit with my camera…

Incredible how the wall winds up and down and sideways over these hills…

I can only imagine how difficult it must have been to attack this wall, ascending the really steep hills, then having to attack these vertical steep walls with bowmen on top (lurking and then shooting from behind a protecting parapet.

The watch towers and signal towers and baracks gave shelter to the soldiers as well. In winter it can get really cold on top of these hills and also the wind makes it feel even colder.

The views over the rolling green hills were amazing and kept me wondering how they could have built this wall.

This part of the wall was called Ming wall, because it was connected and reinforced during the Ming rule. Although the outside of the wall looks like it is made of bricks, it actually isn’t all bricks. The foundations are all stones, shaped into rectangles, because stones can carry a much larger weight and hold easier into place than bricks can. On top of that the walls were created from bricks and filled with stone rubble.

Much more to China’s west, there are still parts of the Han wall to be found. The Han wall is much older than the Ming wall and its structure differed enormously from that of the Ming wall. The Han wall sections were made from rammed earth, stones, and wood.

The Great Wall obviously crosses many old Chinese borders and therefore marker stones indicating such borders were placed on top of the wall to inform its defenders of where they were coming from and where they were going when crossing such borders…

Beneath is an actual border marker stone…

Some of my pictures really show how steep the wall sections really are…

The appeal of Mutianyu is in the beautiful landscape and less obtrusive tourist industry. This section of tge wall originates from 1368 and was built upon the foundations of the wall that was erected by the Northern Qi dynasty (550 – 577 after C.).

It ia about 90 kilometers north of Beijing.

TIPS: The Wandelgek visited the wall on a hot summer’s day when temperatures rose well over 30 degrees Celsius. Apart from the occasional watch tower, there is no shade on the wall. The wall follows the terrain which consists of steep hills and thus the road on top can be very steep.

The weather elemants have great influence on the wall (wind storm rain, snow and sun) meaning that it is wise to dress apropriately. Good shoes that do not slip are important and sunblock maybe a cap and sunglasses are no luxury either. Dress according to weather condition forecasts. Really good walking shoes are a plus when visiting the non restored sections of the wall, like the ones at Simatai.

Important: Bring enough (meaning a lot) water when visiting the wall on a hot summer’s day and a raincoat on a rainy day.

Beneath are some pictures of the hillsides at Mutianyu…

…and of the wall attached like a wrighling snake onto the top of the hills…

I think the hills upon which the wall is built are a promontory of the larger mountain range north of Beijing…

The Wandelgek can honestly advise you to visit Mutianyu’s wall section, because it was not too crowded (try to get there early though) and because it is a really, really beautiful section. It is amazing to see this wall crawling up and down hill, walk over it knowing you are walking upon history.

So here are some more amazing images of the wall…Enjoy!!!

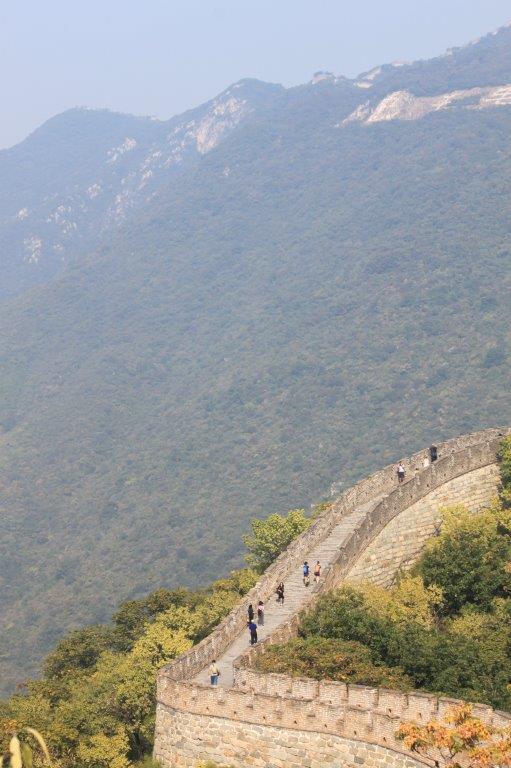

It is possible to follow large stretches of the wall on foot but it’s not easy. The restored parts of the wall are quite good for a walk, although maybe steep and slippery, but the unrestored parts can be right out dangerous. They are actually ruins of the wall and can collapse…

Do not underestimate the steepness of the wall, specially on rainy days when stines get slippery…

There is even wildlife to be found on top of the Great Wall of China…

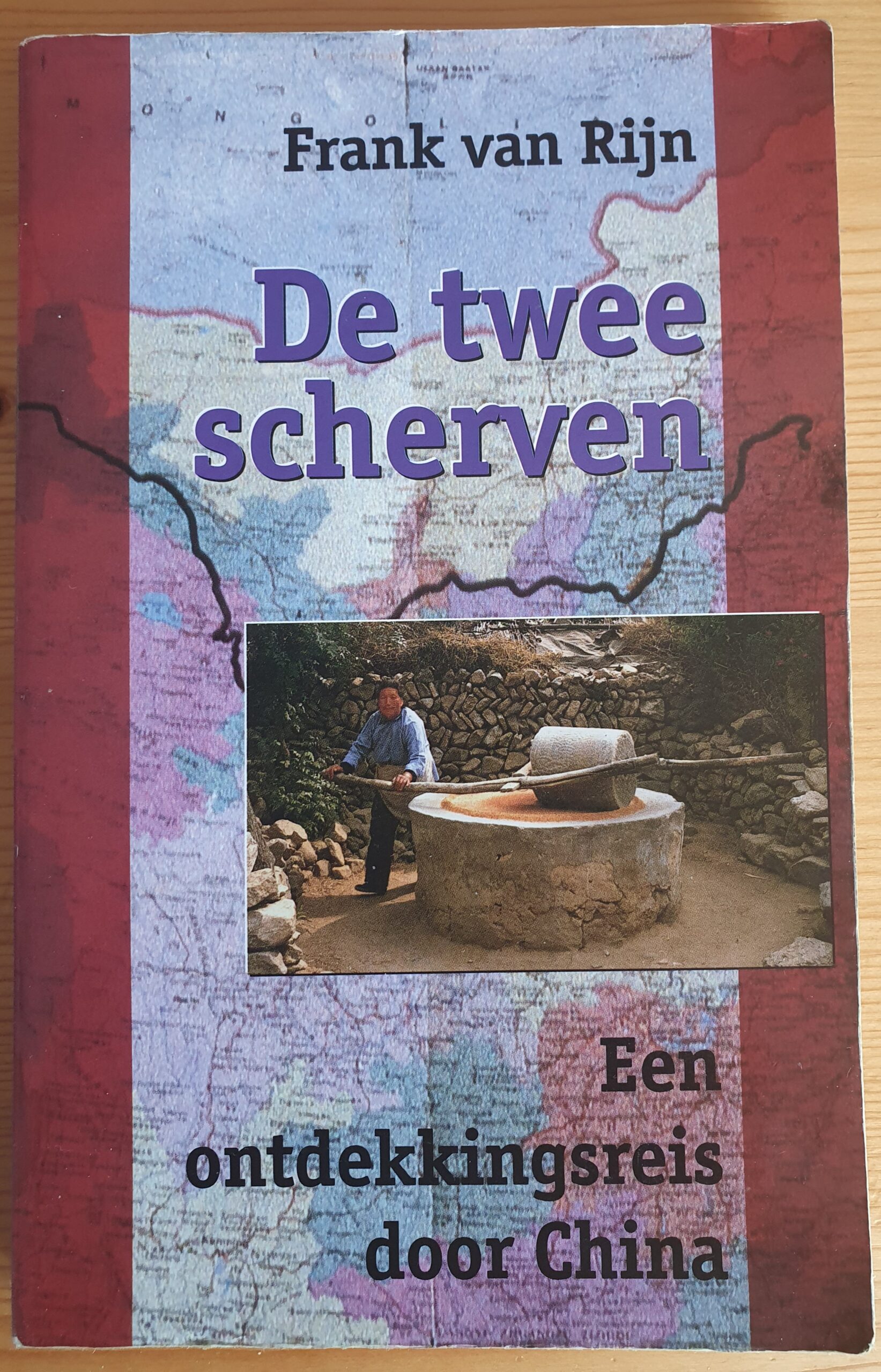

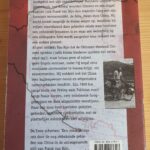

When The Wandelgek was much younger, he read this book by dutch travelbiker Frank van Rijn, which was one of the books that inspired him to visit the wall. The book is about the adventures of a biker travelling through China from Beijing to the border with Pakistan, who follows the Great Wall from Beijing as long as possible until somewhere deep in the Xinjiang province where the wall remnants are almost unrecognizable compared to the restored wall sections near Beijing…

Before The Wandelgek returned towards the Cabin lift to descend to Mutianyu, he stopped walking, paused for a long while and looked around to let it all have some impact on his state of mind. It’s not very difficult to let that happen, looking at a world wonder like this…

Far beneath is the village of Mutianyu…

Cable car ride back to Mutianyu

Then The Wandelgek entered a cable car cabin and descended.

The ride down gives you a last opportunity to see the wall from a greater distance before it disappears behind all the greenery grows upon the hill slopes…

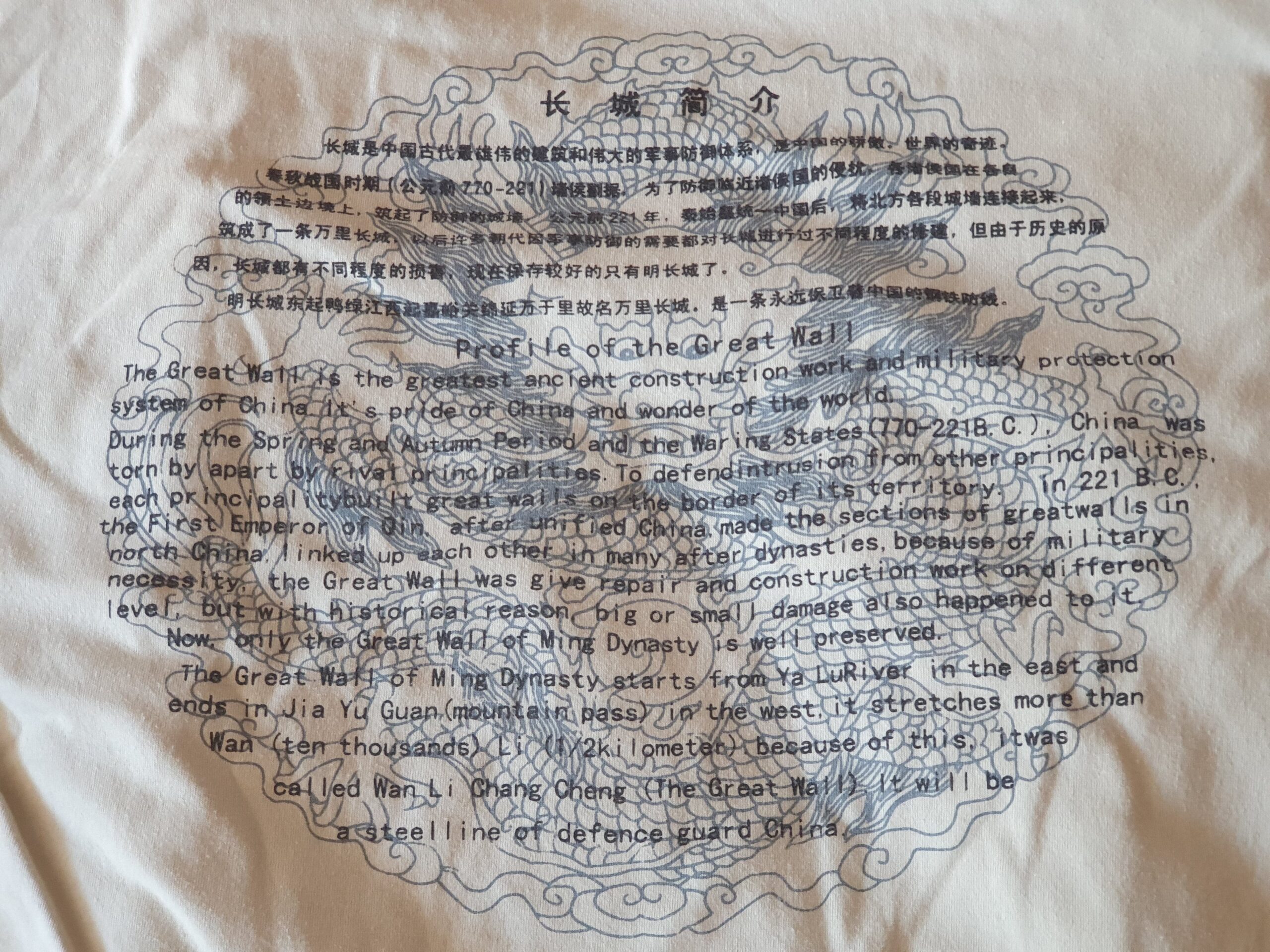

After arriving at the bottom cable station, The Wandelgek visited one of the shops between the station and the bus parking. He bought a few beautiful souvenirs that depicted the Great Wall.

- T-shirt:

- Wall decoration:

After the bus ride the cab driver was waiting for him (really punctual) to go towards the next destination…

More of that in my next blogpost about China.