Origin and development of the Mongolian ger (yurt)

The museum attached to the Genghis Khan Statue has exhibitions relating to the Bronze Age and Xiongnu archaeological cultures in Mongolia, which show everyday utensils, belt buckles, knives, sacred animals, etc. and a second exhibition on the Great Khan period in the 13 and 14th centuries which has ancient tools, goldsmith subjects and some Nestorian crosses and rosaries. But there is also an exhibition regarding the development of the ger through history. The Wandelgek visited that exhibition…

The Mongols as a nomadic tribe

When you come to think of it, it is a rather remarkable feat, that a nomadic tribe like the Mongols were able to conquer such a huge empire, defeating all sorts of non nomadic settlers, some of them living in strongly defended keeps, like fortresses, fortified cities or even castles. The large majority of the Mongols remained nomads for the larger part of this time frame, and only became settlers in the end when the empire fell apart. An example of settling nomads were those of the famous Golden Horde, living in Tatarstan. They assimilated with Turkic tribes like the Tatars and they build cities of which Kazan is the best known as the capital of Tatarstan, conquered by Iwan the Terrible.

More of that in my blogposts: The railroad to Tatarstan: Moscow Kazan (Ural line) and City walk through Kazan: Capital of Tatarstan

These nomadic Mongols lived in gers (or yurts, which is the Russian name) and Genghis Khan who created the site of the later capital of Karakorum near the modern town of Kharkorin and the later built monastery of Erdene Zuu, did not have a real town there, with buildings and city walls, but a large ger camp. It was his son, Kublai Khan who built a real city at Karakorum.

More of that in my blogpost: Some History of Mongolia, Eagle Hunters and Genghis Khan at Karakorum

But almost all Mongols who did not live in Karakorum remained living in gers, which made them a very, very mobile society, always following the cattle herds towards new fresh pastures and learning to live with and from the animals. They were a sturdy folk living a lot outdoors and they really mastered horse riding like no other. Genghis Khan combined this by unifying these tribes and by using superior methods of warfare for superior light weight horse riders. They were much more maneuverable than e.g. the heavier armed European knights and because of their large numbers they could conquer cities or castles, using time as an ally and starve the defenders. This made them very succesful as conquerors.

Knowing the importance of this nomadic lifestyle for their succes, it is obvious to have a closer look at the:

Origin and development of the Mongolian ger

Here’s a brief summary in images of all the stages of development that a ger/yurt went through before achieving its final, modern form:

The above overview (1. The Grass Hut, 2. The Chum, 3. The Tseej Ger, 4. The Tovi Ger, 5. The Sarkhinag roofed and walled Ger, 6. The 1940’s Ger and 7. The Modern Ger) is just a visualization, nothing more.

Beneath I’ll go deeper into each phase of the development of the ger/yurt:

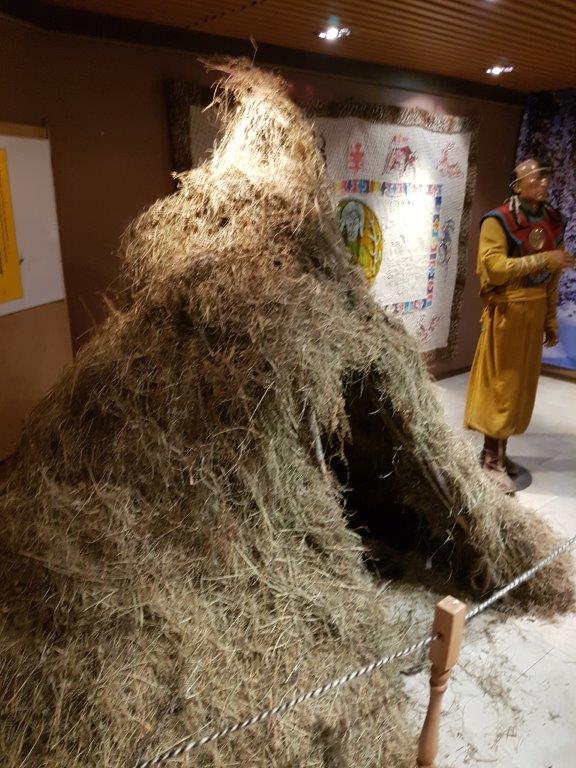

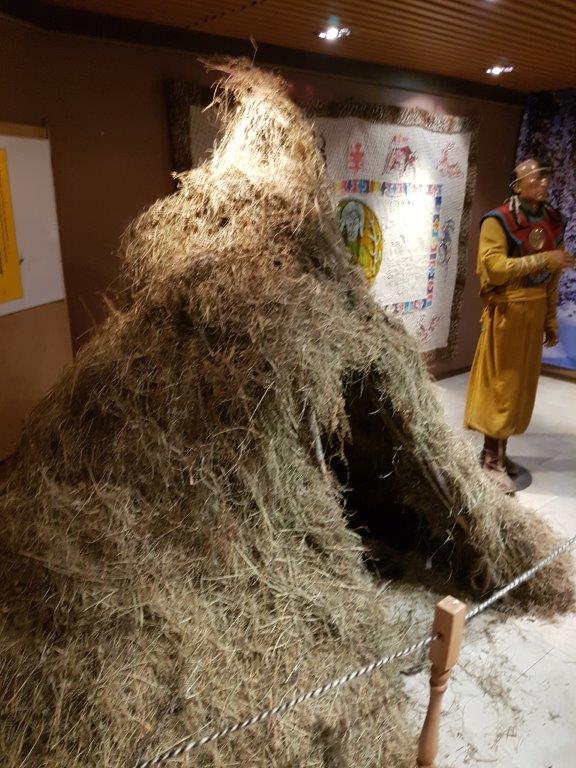

1. The grass hut

A hut is a primitive dwelling, which may be constructed of various local materials. Huts are a type of vernacular architecture because they are built of readily available materials such as wood, snow, ice, stone, grass, palm leaves, branches, hides, fabric, or mud using techniques passed down through the generations.

A hut is a building of a lower quality than a house (durable, well-built dwelling) but higher quality than a shelter (place of refuge or safety) such as a tent and is used as temporary or seasonal shelter or in primitive societies as a permanent dwelling.

Huts exist in practically all nomadic cultures. Some huts are transportable and can stand most conditions of weather.

The oldest known predecessors of the modern ger (yurt) were simple grass/straw huts. They are actually the oldest known lodgings built by humans. Before that humans still lived in caves or other shelters created by nature.

Author: Closelyobserved.com Licenced via Wikicommons: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en

Adjacent to the museum is a tourist and recreation centre, which covers 212 hectares (520 acres).

The exterior of the grass hut is very similar to that of a haystack and it becomes very well imaginable where humans got inspired by when they started to build these very first dwellings.

Exterior

The grass hut is actually very much like a haystack, but the interior is removed to create room and the doorway is somewhat reinforced by wooden sticks…

Interior

There are no specific practical features recognizable inside the Grass hut, except that it protects from wind, rain, sun and cold. However I can’t imagine peopel making a fireplace inside such a volatile hut. Apart from the sparks that could set fire to the whole construction, there is also no route for the smoke to leave the hut. I therefore think a fire would be made in front of the hut and these people had to really keep checking the wind direction…

The next step in the evolution of this type of dwelling really amazed me…

2. The Chum

Now I think that everyone who sees the above images of the Chum, the previous ones of the grass hut and the ones following beneath, without reading the text about the Chum, has immediate associations with the north american tipi. Am I right or am I right?

In a previous blogpost, I’ve already written about the common ancestors of the Asian nomads in Russia and the same seems to be likely for the Mongolian nomads. There are dna equivalences too between the north american inuit (and also other peoples that commonly are collected under the name Eskimos), and the Indians living in the United States.

Tipi or teepee

The Indians of course did live in tipis (although they also used other dwellings, like caves or cave dwellings).

A tipi (/ˈtiːpiː/ TEE-pee), also tepee or teepee and often called a lodge in older English writings, is a tent, traditionally made of animal skins upon wooden poles. Modern tipis usually have a canvas covering. A tipi is distinguished from other conical tents by the smoke flaps at the top of the structure.

A chum (pronounced “choom”) is a temporary dwelling used by the nomadic Uralic (Nenets, Nganasans, Enets, Khanty, Mansi, Komi) reindeer herders of northwestern Siberia of Russia. The Evenks, Tungusic peoples, tribes, in Russia, Mongolia and China also use chums. They are also used by the southernmost reindeer herders, of the Todzha region of the Republic of Tyva and their cross-border relatives in northern Mongolia. It has a design similar to a Native American tipi but some versions are less vertical.

It is very closely related to the Sami lavvu in construction, but is somewhat larger in size. Some chums can be up to thirty feet (ten meters) in diameter.

Lavvu

Lavvu (or Northern Sami: lávvu, Lule Sami: låvdagoahte, Inari Sami: láávu, Skolt Sami: kååvas, Kildin Sami: koavas, Finnish: kota or umpilaavu, Norwegian: lavvo or sametelt, and Swedish: kåta) is a temporary dwelling used by the Sami people of northern extremes of Northern Europe. It has a design similar to a Native American tipi but is less vertical and more stable in high winds. It enables the indigenous cultures of the treeless plains of northern Scandinavia and the high arctic of Eurasia to follow their reindeer herds. It is still used as a temporary shelter by the Sami, and increasingly by other people for camping. It should not be confused with the goahti, another type of Sami dwelling, or the Finnish laavu.

A Sami family in front of a goahti in the foreground and a lavvu in the background (the picture is taken around 1900). Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

There are several historical references that describe the lavvu structure (also called a kota, or a variation on this name) used by the Sami. These structures have the following in common:

- The lavvu is supported by three or more evenly spaced forked or notched poles that form a tripod.

- There are upwards of ten or more unsecured straight poles that are laid up against the tripod and which give form to the structure.

- The lavvu does not need any stakes, guy-wire or ropes to provide shape or stability to the structure.

- The shape and volume of the lavvu is determined by the size and quantity of the poles that are used for the structure.

- There is no center pole needed to support this structure.

No historical record has come to light that describes the Sami using a single-pole structure claimed to be a lavvu, or any other Scandinavian variant name for the structure. The definition and description of this structure has been fairly consistent since the 17th century and possibly many centuries earlier.

The goahti, also used by the Sami, has a different pole configuration. While trees suitable to make lavvu poles are quite easy to find and often left at the site for later use, the four curved poles of the goahti have to be carried.

Modern Lavvu’s use stronger, more durable and more light weight textiles and aluminum instead of wooden poles.

The traditional chum consists of reindeer hides sewn together and wrapped around wooden poles that are organized in a circle. In the middle there is a fireplace used for heating and to keep the mosquitoes away. The smoke escapes through a hole on top of the chum. The canvas and wooden poles are usually quite heavy, but could be transported by using their reindeer. The chum is still in use today as a year-round shelter for the Yamal-Nenets, Khanty and Todzha Tyvan people of Russia.

In Russian use, the terms chum, yurt and yaranga may be used interchangeably.

The word chum (Russian: чум) came from Komi: ćom [t͡ɕom] or Udmurt: ćum [t͡ɕum], both mean “tent, shelter”. In different languages it has different names: Nenets: ḿāʔ [mʲaːʔ], Nganasan: maʔ, Khanty: (ńuki) χot. Evenki: ǯū [d͡ʒuː].

Exterior

Extremely important improvements versus the grass hut are the use of animal skins (The Nenets e.g. kept Reindeer and they also had domesticated wolves that had developed into dogs) which isolate far better than the grass/hay did, possibility to close the doorway with a flap of animal skin and the air hole in the roof which allowed people to make a fireplace inside of the chum. The smoke curls up and leaves through the air hole.

Interior

The interior is obviously much more comfortable than that of a bare grass hut. The floor is covered with warm isolating animal skins and there is room for a chest and a cooking place. No room for a bed yet though.

The interior is obviously much more comfortable than that of a bare grass hut. The floor is covered with warm isolating animal skins and there is room for a chest and a cooking place. No room for a bed yet though.

3. Tseej ger

The next evolutionary step is that of the Tseej ger…

3. The Tseej ger is a dwelling that came after the Chum and had a roof on the top. It had been used widely by Indian…

Exterior

The Tseej ger is the 1st ger-like dwelling. It is broader and has a rounder shape at the top. It also comes with… a (removable) roof, but it it still lacks real walls.

Interior

The interior becomes a lot more spacious than that of the Chum, which allows people to stand straight in a larger area and place more furniture at the edges of the space, like e.g. a table and a larger trunk. There is more space around the cooking area too.

4. Tovi ger

Another predecessor of the ger is the Tovi ger and it has again north american associations too.

4. A Tovi ger is a dwelling that precedes the contemporary Walled ger. It is constructed by securing the rafters (poles) to the ground, forming a rounded cone shape at the top. It had been used widely by Mongolian people.

Although the Tovi is dressed with animal skins, it does ring a bell and reminds us of a shape which was seen on the American plains, used by Indians. I’m thinking of:

The Wigwam

A wigwam, wickiup, wetu, or wiigiwaam in the Ojibwe language, is a semi-permanent domed dwelling formerly used by certain Native American tribes and First Nations people. They are still used for ceremonial events. The term wickiup is generally used to label these kinds of dwellings in the Southwestern United States and Western United States, while wigwam is usually applied to these structures in the Northeastern United States as well as eastern Canada (Ontario and Quebec). Wetu is the Wampanoag term for a wigwam dwelling. These terms can refer to many distinct types of Native American structures regardless of location or cultural group. The wigwam is not to be confused with the Native Plains teepee, which has a very different construction, structure, and use.

Structure

The domed, round shelter was used by numerous northeastern Native American tribes. The curved surfaces make it an ideal shelter for all kinds of conditions. Indigenous peoples in the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence Lowlands resided in either wigwams or longhouses.

These structures are made with a frame of arched poles, most often wooden, which are covered with some sort of bark roofing material. Details of construction vary with the culture and local availability of materials. Some of the roofing materials used include grass, brush, bark, rushes, mats, reeds, hides or cloth.

Exterior

A Tovi ger can, is because of its rounder shape contain still more space inside and the area where people can stand upright is larger too, but nor the limits of this type of dwelling, which can be very well compared to a very large dome shaped tent used by hikers, with curved poles attached to the ground.

Interior

Inside the even more voluminous Tovi ger, we see the first trials of seats and beds at the very verge of the room. There is also a small table in the middle and a tea pot, suggesting that luxury is at last slowly entering the human dwellings…

Inside the even more voluminous Tovi ger, we see the first trials of seats and beds at the very verge of the room. There is also a small table in the middle and a tea pot, suggesting that luxury is at last slowly entering the human dwellings…

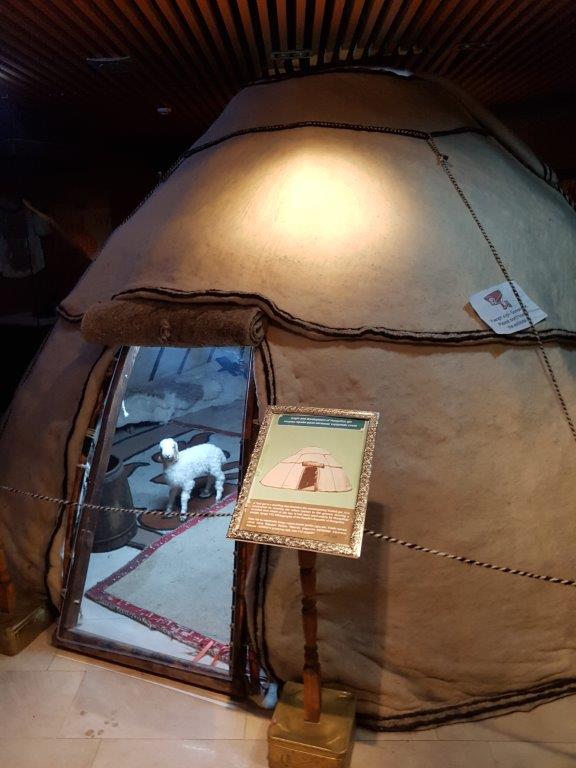

5. The Sarkhinag

Next in the evolutionary line is the Sarkhinag, which is the first roofed and walled ger in history…

5. Sarkhinag roofed and walled ger… It is a type of ger that precedes the modern ger and had incorporated a wall in its design…

Exterior

The Sarkhinag marks the first model of a dwelling where we recognize elements of a modern ger and where we see that the devolpment of north american native dwellings and Asia native dwellings start to diverge in their development.

The exterior of a Sarkhinag, for the very 1st time makes use of a wooden foldable and flexible fence like wall. Animal skins are attached to it on the outside. The wall strengthens the structure considerably and enables it to become larger than its predecessors had been. Furthermore it enables people to stand straight in the complete volume of the Sarkhinag, even when standing against or almost against its wall.

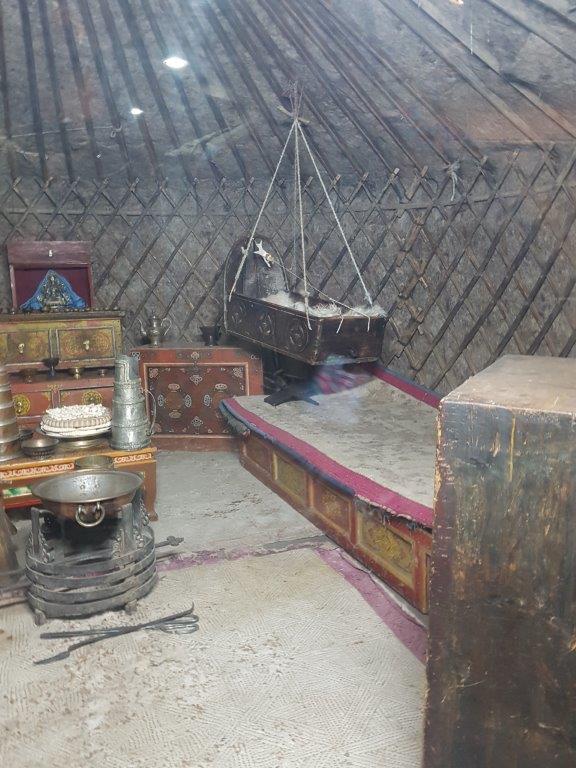

Interior

The Sarkhinag clearly increases the living room within the dwelling. Furniture gets larger, people move through the Sarkhinag without hindering one another.

We are now getting to the end of the evolution of the ger.

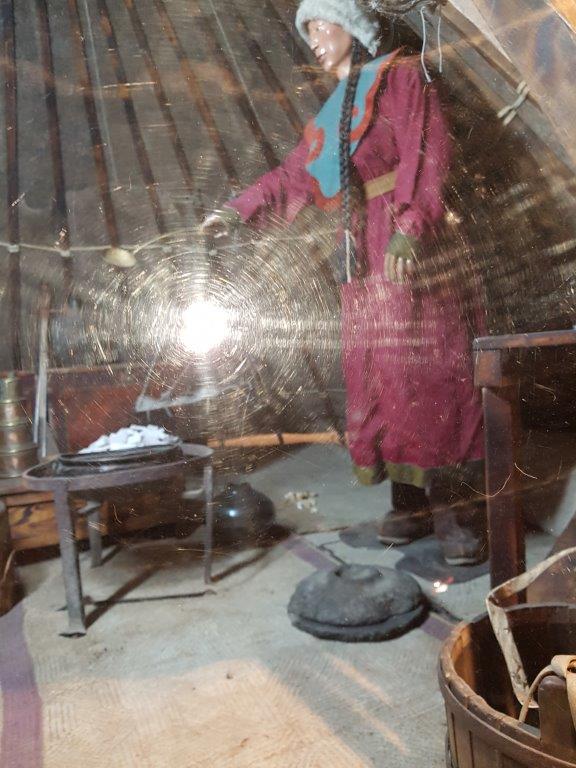

6. Mongolian ger of the 1940s

Exterior

Exterior

The external materials are of a better quality than before. A steel or aluminum pipe leaves the top of the ger indicating that a real stove has now entered the interior of the ger. No smoke anymore within the ger. The door is still covered with a piece of animal skin that could be rolled up and attached to the top of the entrance when it should stay open.

The external materials are of a better quality than before. A steel or aluminum pipe leaves the top of the ger indicating that a real stove has now entered the interior of the ger. No smoke anymore within the ger. The door is still covered with a piece of animal skin that could be rolled up and attached to the top of the entrance when it should stay open.

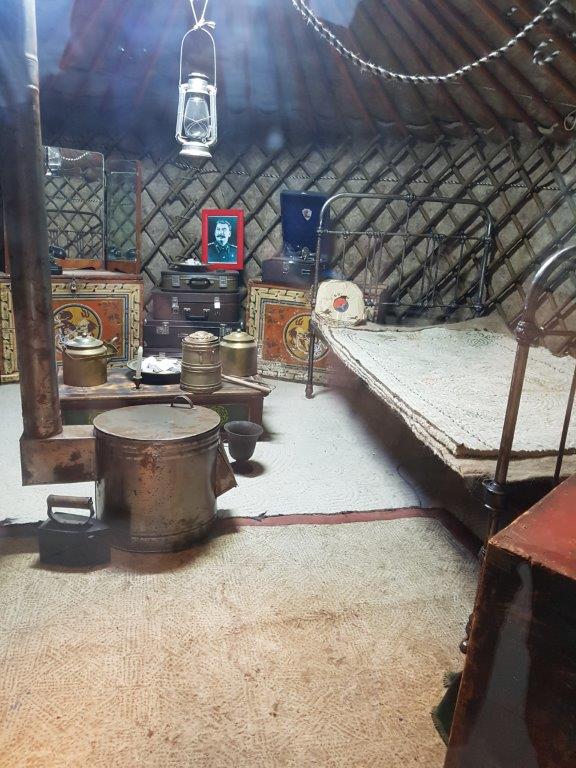

Interior

Real beds and even some cupboards, a tele and a larger sized stove with an exhaust pipe/chimney attached to it. This predecessor of the modern ger has already a lot of the elements that we see now in today’s gers/yurts. A television suggests that somewhere there is an energy source for this ger, but in the 1940’s that can not have been a solar cell. Probably a generator is positioned near the ger, or more obvious, the ger is attached to the electricity wires of the electricity network. In the 1940’s that probably meant this ger was located near a town.

7. Modern ger or yurt

Exterior

The exterior wall is now surrounded by multiple layers like felt for isolation and a textile cover to protect the felt aganst weather influences. Also an often richly adorned wooden door is added to the ger entrance, replacing the piece of animal skin that covered the door before.

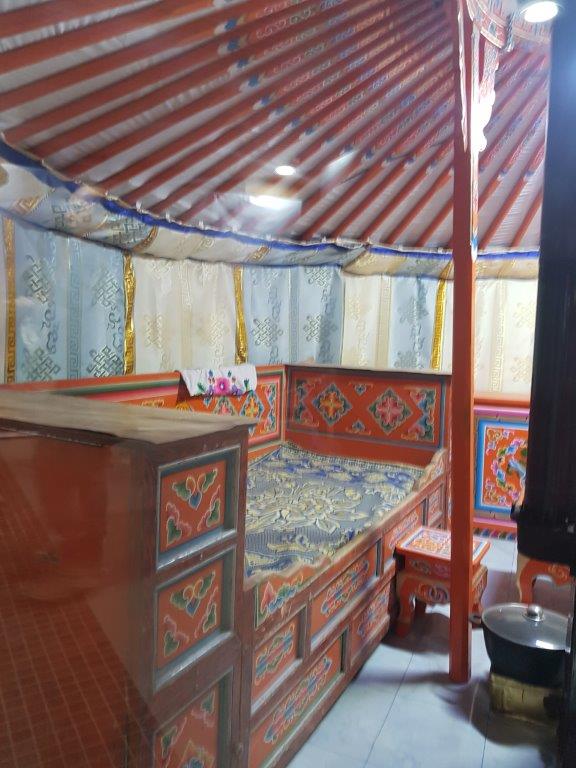

Interior

Main changes to this ger type are a large top air hole which is supported by a construction of a wooden circle and 4 wooden bars making some sort of a tic Tac Toe raster. This larger airhole provides more room for for a larger more powerful stove chimney and still leaves space for fresh air to enter the ger. Whenever it rains or snows or is too cold, this air hole is covered and the ger is isolated and gets warm again. The stove functions as a stove and as a heating source as well. Another change is mainly meant to please the eye. It is decorated textile to cover the inside of the ger walls.

You can see much more space for large more luxourious beds, cupboards and still the obligatory altar and then there is room enough to walk around to provided you do this in the prescribed direction which us clockwise around the central poles.

The again substantially larger space underneath the now rather large wooden circle of the air hole in theroof is now supported by one or two poles (depending on its size) in the center of the ger. The stove is in between those poles. The wooden circle is often kept in its position by a heavy stone, attached to a rope, attached to that wooden circle and hanging in the center of the ger like this:

In this pic you can see the two poles supporting the circular wooden airhole structure of the roof, the stove with a piece of the metal chimney going up through the airhole and a heavy stone attached to the wooden airhole structure of the roof, keeping it in position, even when there’s a heavy gailstorm…

The wooden roof piece looks like this:

An abstracter shape of this top piece of a ger or yurt, has made it into the Kyrgyz national flag:

The separate elements of a modern ger

Transportation

Transportation

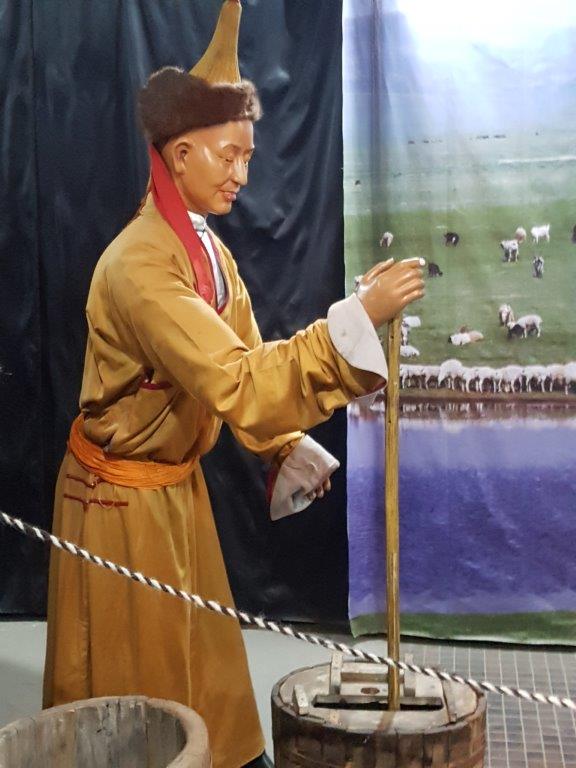

The whole idea of a nomadic dwelling is that it is either easy to built from materials found wherever the nomads travel, or easy to build and to unassemble and easy to transport elsewhere. Even the large modern ger is still easy to transport on one cart, pulled by a camel, a horse or maybe an ox.

At the railway station of Ulaanbaatar I saw the materials of a ger that were transported on the train, being reloaded on such a wheelcart and than leaving the station…

All parts of the yurt, like the wooden floor parts, the door, the felt surroundings, the protecting outer textiles, the inner textiles decorating the wall, the supporting poles, the wooden top piece, the poles that go on top of the wall and the wall itself all fit neatly on one wheelcart…

All parts of the yurt, like the wooden floor parts, the door, the felt surroundings, the protecting outer textiles, the inner textiles decorating the wall, the supporting poles, the wooden top piece, the poles that go on top of the wall and the wall itself all fit neatly on one wheelcart…

Power

Modern gers are often connected to the electricity net of Mongolia which is an above ground network,…

…but lots of gers also own one or more solar cells to provide the necessary power to reload batteries of mobile and smart phones :-)..

Conclusion

The ger or yurt is the end product of a very efficient dwelling for nomadic tribes and probably it will develop further for nomads as well as for tourists/travellers. It was the end product in a long line of dwellings that were created by nomadic tribes all over the northern hemisphere ranging from Mongolia into Siberia to Russia, Scandinavia and either accross the Atlantic via iceland and greenland towards Canada or accross the Pacific via the islands in the Bering street towards Alaska and Canada and south into the US, Mexico and even Central America. It’s attractiveness was in it being easily built, easily deconstructed and easily transported, which is crucial in a nomadic society.

The Wandelgek left the museum to enter the fresh Mongolian air and to engage in another outdoor adventure, but that is another story for another upcoming blogpost.