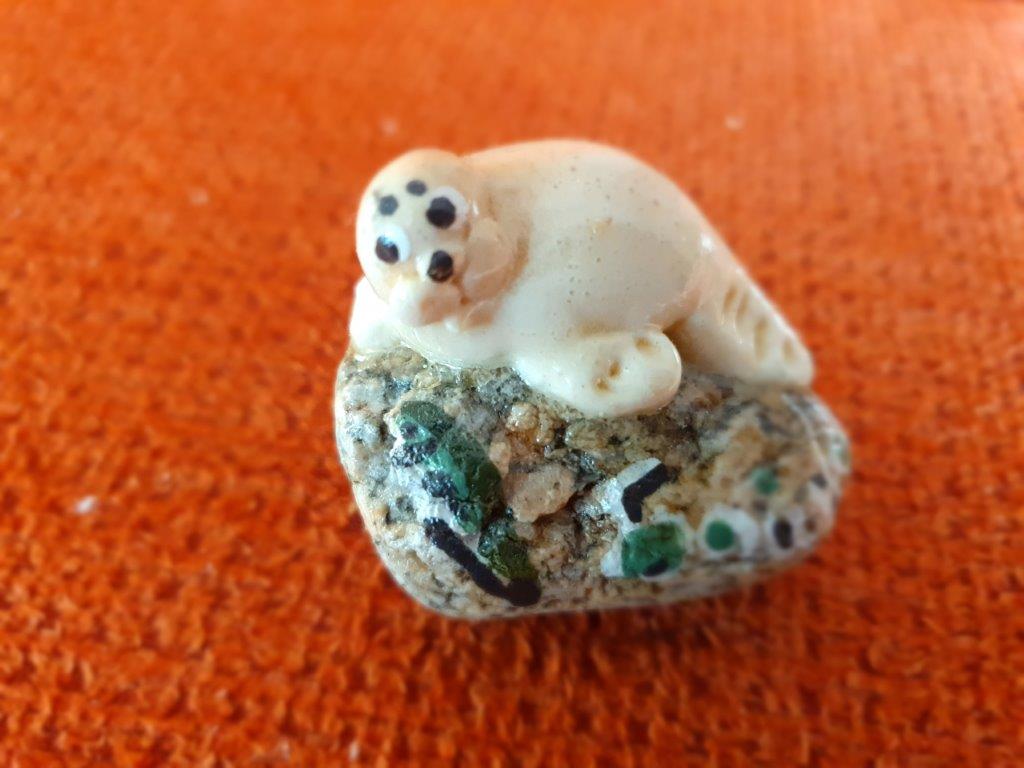

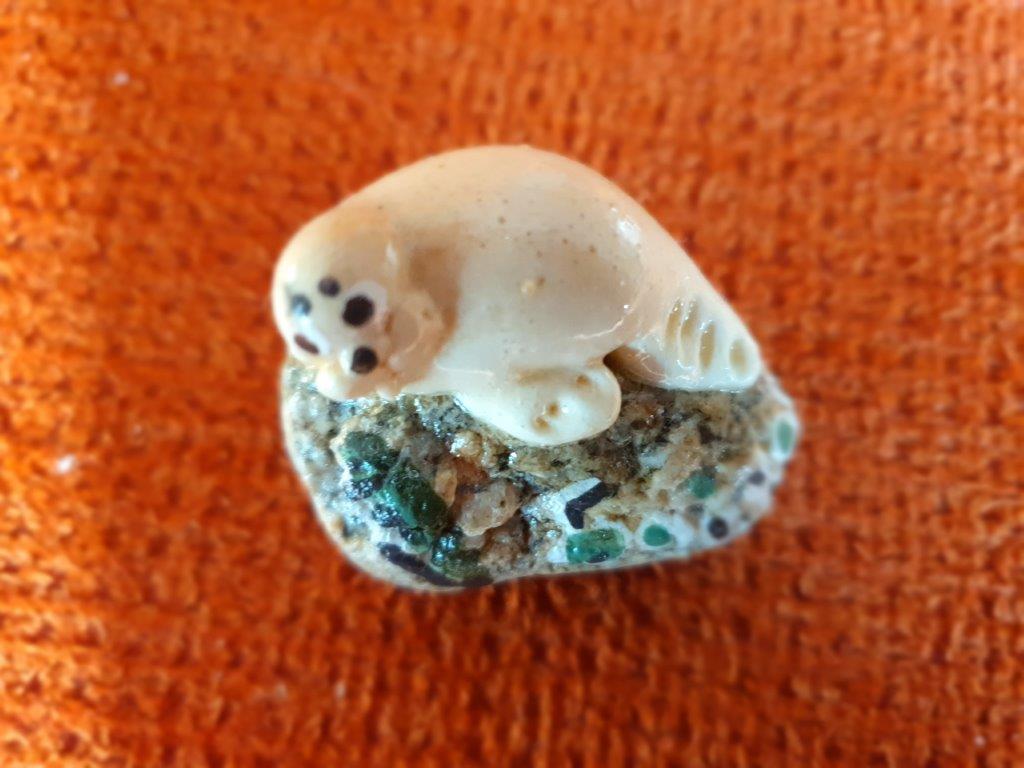

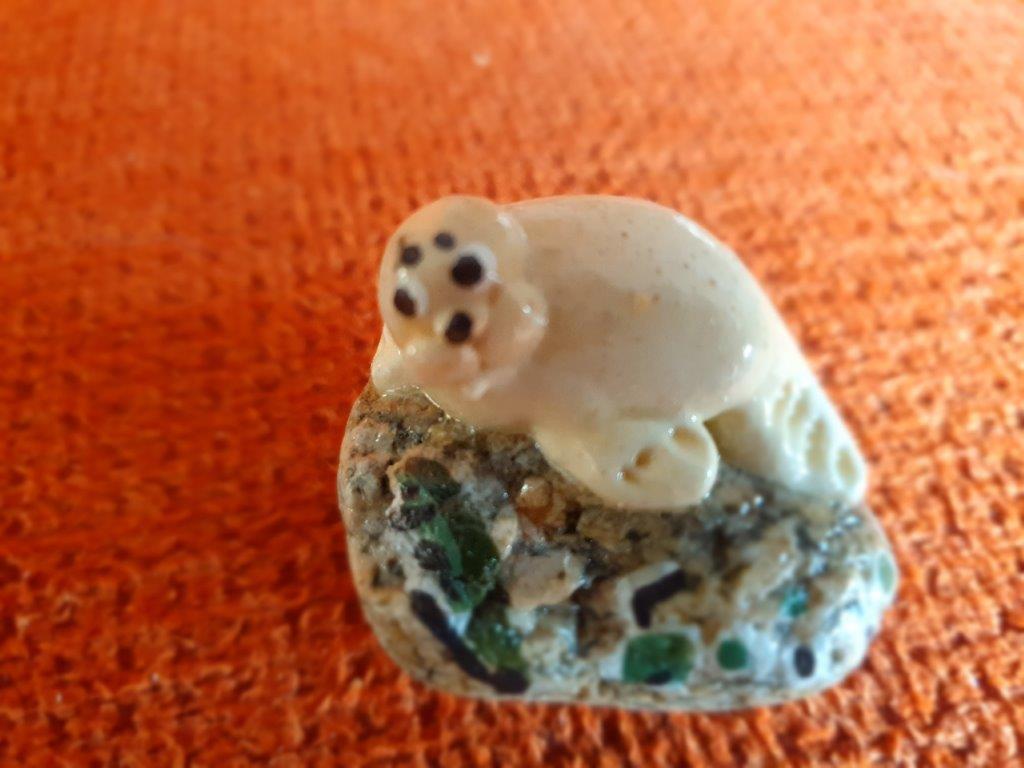

Souvenir 008: Nerpa/Baikal Seal statuette, painted and glazed pebble stone – Lake Baikal, Russia 2019

Tiny statuette of a Baikal or Nerpa seal, created by painting and glazing a pebble stone found on the shores of Lake Baikal.

These statuettes are created in large amounts, all hand painted and from pebble stones that are useable and everyone is unique.

I received this little statuette from a Russian family, living in a dacha near Lake Baikal, where I was invited for dinner, as something to remember Lake Baikal by. Read more in my blogpost: Dinner in a Russian Dacha (Pribaikalsky National Park/Lake Baikal – UNESCO World Heritage site)

The Baikal or Nerpa Seal

The Baikal seal, Lake Baikal seal or nerpa (Pusa sibirica), is a species of earless seal endemic to Lake Baikal in Siberia, Russia. Like the Caspian seal, it is related to the Arctic ringed seal. The Baikal seal is one of the smallest true seals and the only exclusively freshwater pinniped species. A subpopulation of inland harbour seals living in the Hudson Bay region of Quebec, Canada (Lacs des Loups Marins harbour seals), the Saimaa ringed seal (a ringed seal subspecies) and the Ladoga seal (a ringed seal subspecies) are found in fresh water, but these are part of species that also have marine populations.

The most recent population estimates are 80,000 to 100,000 animals, roughly equaling the expected carrying capacity of the lake. At present, the species is not considered threatened.

Description

The Baikal seal is one of the smallest true seals. Adults typically grow to 1.1–1.4 m (3 ft 7 in–4 ft 7 in) in length with a body mass from 63 to 70 kg (139 to 154 lb). The maximum reported size is 1.65 m (5 ft 5 in) in length and 130 kg (290 lb) in weight. There are significant annual variations in the weight, with lowest weight in the spring and highest weight, about 38–42% more, in the fall. The animals show very little sexual dimorphism; males are only slightly larger than females. They have a uniform, steely-grey coat on their backs and fur with a yellowish tinge on their abdomens. As the coat weathers, it becomes brownish. When born, the pups weigh 3–3.5 kg (6.6–7.7 lb) and are about 70 cm (2 ft 4 in) long. They have coats of white, silky, natal fur. This fur is quickly shed and exchanged for a darker coat, much like that of adults. Rarely, Baikal seals can be found with spotted coats.

Distribution

The Baikal seal lives only in the waters of Lake Baikal. It is something of a mystery how Baikal seals came to live there in the first place. They may have swum up rivers and streams or possibly Lake Baikal was linked to the ocean at some point through a large body of water, such as the West Siberian Glacial Lake or West Siberian Plain, formed in a previous ice age. The seals are estimated to have inhabited Lake Baikal for some two million years.

The areas of the lake in which the Baikal seals reside change depending on the season, as well as other environmental factors. They are solitary animals for the majority of the year, sometimes living kilometres away from other Baikal seals. In general, a higher concentration of Baikal seals is found in the northern parts of the lake, because the longer winter keeps the ice frozen longer, which is preferable for pupping. However, in recent years, migrations to the southern half of the lake have occurred, possibly to evade hunters. In winter, when the lake is frozen over, seals maintain a few breathing holes over a given area and tend to remain nearby, not interfering with the food supplies of nearby seals. When the ice begins to melt, Baikal seals tend to keep to the shoreline.

Abundance and trends

Since 2008, the Baikal seal has been listed as a Least Concern species on the IUCN Red List. This means that they are not currently threatened or endangered. In 1994, the Russian government estimated that they numbered 104,000. In 2000, Greenpeace performed its own count and found an estimated 55,000 to 65,000 seals. The most recent estimates are 80,000-100,000 animals, roughly equaling the carrying capacity of the lake.

In the last century, the kill quota for hunting Baikal seals was raised several times, most notably after the fur industry boomed in the late 1970s and when official counts began indicating more Baikal seals were present than previously known. The quota in 1999, 6,000, was lowered in 2000 to 3,500, which was still nearly 5% of the population if the Greenpeace count is correct. In 2013–2014, the hunting quota was set at 2,500. In addition, new techniques, such as netting breathing holes and seal dens to catch pups, have been introduced. In 2001, a prime seal pelt would bring 1,000 rubles at market. In 2004–2006, about 2,000 seals were killed per year according to official Russian statistics, but in the same period another 1,500–4,000 are thought to have died annually due to drowning in fishing gear, poaching, and the like. In 2012–2013, it was estimated that 2,300–2,800 were hunted per year (combined legal hunting and poaching). Some groups have pressured for higher hunting quotas.

Another problem at Lake Baikal is the introduction of pollutants into the ecosystem. Pesticides such as DDT and hexachlorocyclohexane, as well as industrial waste, mainly from the Baikalisk pulp and paper plant, are thought to have exacerbated several disease epidemics among Baikal seal populations. The chemicals are speculated to concentrate up the food chain and weaken the Baikal seal’s immune system, making them susceptible to diseases such as canine distemper and the plague, which was the cause of a serious Baikal seal epidemic that resulted in the deaths of 5,000–6,500 animals in 1987–1988. Small numbers died as recently as 2000, but the reason for their deaths is unclear. Canine distemper is still present in the Baikal seal population, but has not caused mass deaths since the earlier outbreaks. In general, levels of DDT and non-ortho PCB have declined in the lake from the 1990s, levels of mono-ortho PCB has showed no change, and perfluorochemical increased. Industrialization of the area near Lake Baikal is increasing and future monitoring is necessary. At present, Baikal seals show lower levels of contaminants than seals of Europe and North America, but higher than those in the Arctic.

The most serious future threat to the survival of the seal may be global warming, which has the potential to seriously affect a closed cold-water ecosystem such as that of Lake Baikal.

The only known natural predator of adult Baikal seals is the brown bear, but this is not believed to occur frequently. The seal pups are typically hidden in a den, but can fall prey to smaller land predators such as the red fox, the sable and the white-tailed eagle.

Reproduction

Female Baikal seals reach sexual maturity at 3–6 years of age, whereas males achieve it around 4–7 years. The males and females are not strongly sexually dimorphic. Baikal seals mate in the water towards the end of the pupping season. With a combination of delayed implantation and a nine-month gestation period, the Baikal seals’ overall pregnancy is around 11 months. Pregnant females are the only Baikal seals to haul out during the winter. The males tend to stay in the water, under the ice, all winter. Females usually give birth to one pup, but they are one of only two species of true seals with the ability to give birth to twins. Very rarely, triplets or quadruplets have been recorded. The twins often stick together for some time after being weaned. The females, after giving birth to their pups on the ice in late winter, become immediately impregnated again, and often are lactating while pregnant.

Baikal seals are slightly polygamous and slightly territorial, although not particularly defensive of their territory. Males mate with around three females if given the chance. They then mark the female’s den with a strong, musky odor, which can be smelled by another male if he approaches. The female raises the pups on her own; she digs them a fairly large den under the ice, up to 5 m (16 ft) in length, and more than 2 m (6 ft) wide. Pups as young as two days old then further expand this den by digging a maze of tunnels around the den. Since the pup avoids breaking the surface with these tunnels, this activity is thought to be mainly for exercise, to keep warm until they have built up an insulating layer of blubber.

Baikal seal pups are weaned after 2–2.5 months, occasionally up to 3.5 months. During this time, the pups can increase their birth weight five-fold. After the pups are weaned, the mother introduces them to solid food, bringing amphipods, fish, and other food into the den.

In spring, when the ice melts and the dens usually collapse, the pup is left to fend for itself. Growth continues until they are 20 to 25 years old.

Every year in the late winter and spring, both sexes haul themselves out and begin to moult their coat from the previous year, which is replaced with new fur. While moulting, they refrain from eating and enter a lethargic state, during which time they often die of overheating, males especially, from lying on the ice too long in the sun. During the spring and summer, groups as large as 500 can form on the ice floes and shores of Lake Baikal. Baikal seals can live to over 50 years old, exceptionally old for a seal, although the females are presumed to be fertile only until they are around 30.

Foraging

Their main food source is the golomyanka, a cottoid oilfish found only in Lake Baikal. Baikal seals eat more than half of the annual produced biomass of golomyanka, some 64,000 tons. In the winter and spring, it is estimated that more than 90% of its food consists of golomyankas. The remaining food sources for this seal are various other fish species, especially Cottocomephorus (about 7% of the diet during the winter and spring) and Kessler’s sculpin (about 0.3% of the diet in the winter and spring), but it may also take some invertebrates such as Epischura baikalensis, gammarids and molluscs. During the autumn the Baikal seal eats 50-67% fewer golomyankas than in the winter and spring, but significantly more Cottocomephorus, Kessler’s sculpins and stone sculpins. A total of 29 fish species have been recorded in the diet. They feed mainly during twilight and at night, when golomyankas occur in depths as shallow as 10–25 m (33–82 ft). During the day, golomyankas are typically found deeper than 100 m (330 ft). Baikal seals can dive up to depths of 400 m (1,300 ft) and more than 40 minutes. Most dives last less than 10 minutes and generally only 2–4 minutes. Baikal seals have two litres more blood than any other seal of their size and can stay underwater for up to 70 minutes if they are frightened or need to escape danger.

According to a 2004 paper on the foraging tactics of baikal seals, during the summer nights these seals are known to have different foraging strategies during night time and during day time. During the day, these seals use visual clues to search for their prey, which is mainly fish, while during the night they use tactile clues to hunt crustaceans. Since it’s brighter during the day, the seals are able to see much better in order to hunt for the fish. Since there’s no light at night, they have to hunt with tactile cues. The crustaceans they hunt at night have a diel migration, so they come up into shallower waters during the night, and swim to deeper waters during the day to escape predators. These seals were observed to dive deeper during dawn and dusk in order to get to these crustaceans as they were swimming shallower and deeper, respectively.

The Baikal seal has been blamed for drops in omul numbers, but this is not the case. It is estimated that omul only comprises about 0.1% of its diet. The omul’s main competitor is the golomyanka and by eating tons of these fish a year, Baikal seals cut down on the omul’s competition for resources.

Baikal seals have one unusual foraging habit. In early autumn, before the entire lake freezes over, they migrate to bays and coves and hunt Kessler’s sculpin, a fish that lives in silty areas and, as a result, usually contains grit and silt in its digestive system. This grit scours the seals’ gastrointestinal tracts and expels parasites.

Read more about the wildlife of Lake Baikal in my blogpost: Lake Baikal Museum (Pribaikalsky National Park/Lake Baikal – UNESCO World Heritage site)