Visiting a nomad family, horses, bactrian camels and living in a ger (Khögnö Khan NR)

The Wandelgek had arrived in the Köghnö Khan Nature Reserve where he was going to stay in a ger campsite for a few days.

Köghnö Khan Uul Nature Reserve

Khogno Khan Uul Nature Reserve (Mongolian: Хөгнө Хан Уул) is centered on Khogno Khan Mountain, about 60 km east of Kharakoram. The park features many historical sites, including the ruins of a 17th-century monastery. It is located in Gurvanbulag District of Bulgan Province, about 240 km west of Ulaanbaatar.

This 469 sq kilometres sized nature reserve centres on a large, boulder-strewn rocky mountain that rises up surreally from its semidesert surroundings. The area is ideal for hiking, walking and even rock clambering and The Wandelgek had a swell time. The area is not far from the largest area of sand dunes outside of the Gobi desert, in Mongolia. There are also some historic sites that he visited but more of that later.

Ger campsite

The Wandelgek spend several nights at a ger campsite which was build in the shadow of the beforementioned boulder-strewn rocky mountain. Here’s an impression of the ger interior and a pic of the ger campsite…

Visit to a nomad family

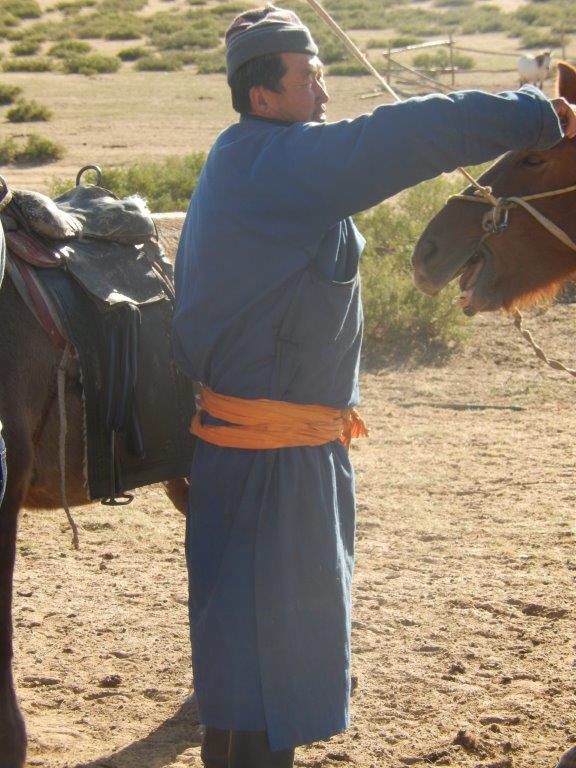

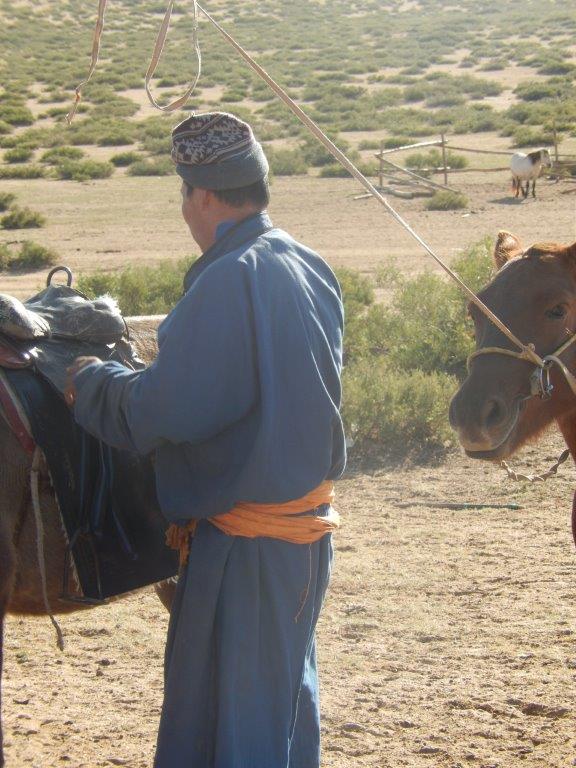

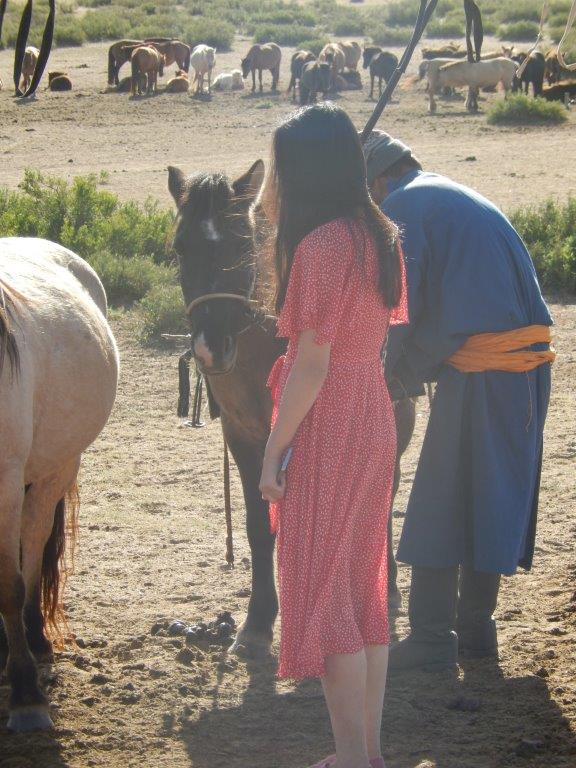

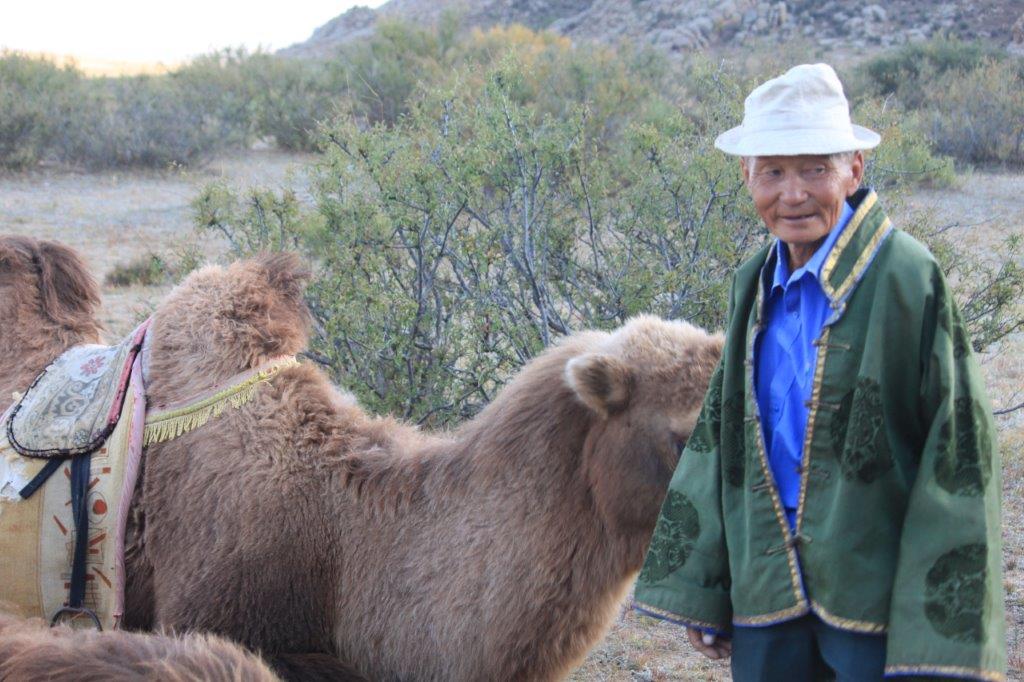

In the area near to the sand dunes, were some nomadic Mongols living in traditional gers, offering horse and camel rides to travellers and tourists.

The Wandelgek decided to visit such a nomadic family to see how they lived here and whether he could detect differences in life style with the nomadic families he visited before while travelling through Xinjiang and Kyrgyzstan.

In the end I noticed that there were no significant differences in the way these nomad families lived, compared between 2004 and 2019.

Back in 2004 I already noticed that the yurts of the Kyrgyz and Khazak nomads were equiped with solar panels and yes the Mongolic gers I had been visiting in 2019 still had solar panels to rely on for energy.

Notice the solar panel strapped to the roof of this Kyrgyz yurt (Karakoram Highway, Xinjiang – China, 2004)

The Wandelgek visited this ger in 2019, now the solar panel was attached upon a standard and it looked larger and more modern.

After the bus arrrived at the ger site where the family lived, The Wandelgek looked around, noticing that there were several other gers being built.

Building a ger

I wrote quite extensively about “yurt”- building before in this blogpost:

Hiking in the Tien Shan / Heavenly Mountains on the shores of Tian Chi / Heavenly Lake

The gers being built were in different phases of completion, which meant that the manner in which a ger is built was visible.

In phase 2, the roof is built and the external cover of weather resilient fabric or created from animal skins (both types of covers are used) is attached to the yurt.

In phase 3, the internal layers of felt made from animal hair are placed. These layers are the isolation layers to keep the ger cool in summer and warm in winter (ger in the foreground). In phase 4, the external layer is placed around the ger and fastened (ger in the background)

These extra gers were probably meant to accommodate tourists…

In the final 5th phase the ger is finished, e.g. by finishing its interior by placing furniture and the stove. More views of the interior can be seen later in this blogpost.

Nomads live in gers or yurts because they can be built and torn down within a day. Then the parts can be packed on horses or on yaks (in Tibet) and transported. Nowadays there are also waggons to transport a collapsed yurt. This heightens their flexibility and enables them to quickly follow a herd of cattle, like cows, horses, sheep, goats, camels or yaks.

Horses and Camels

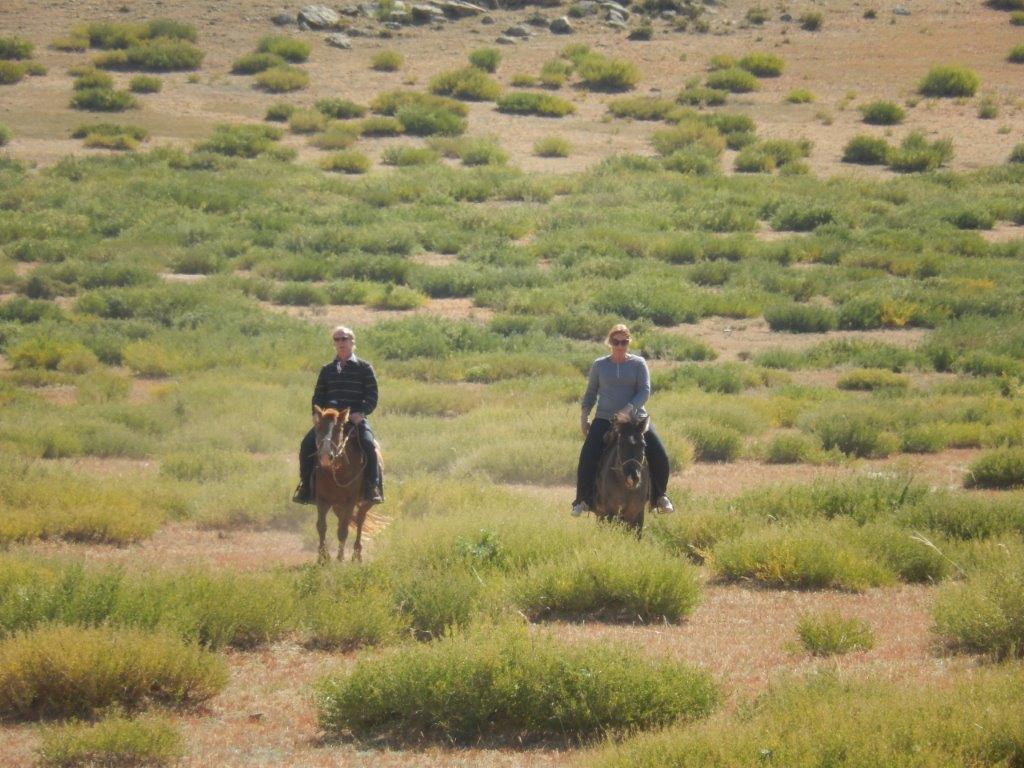

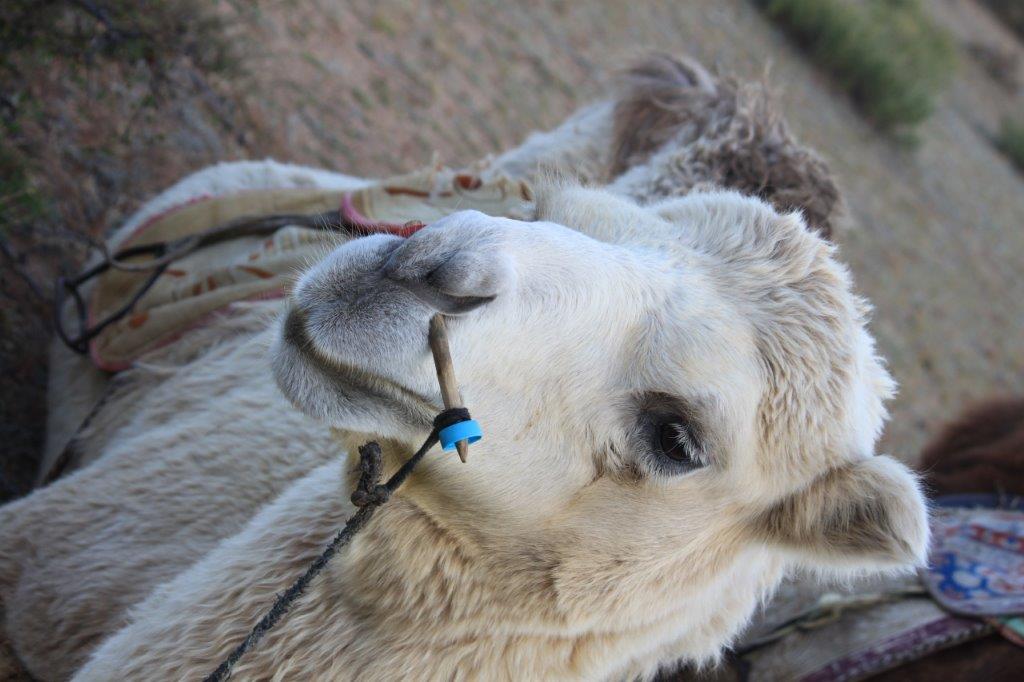

The nomad family that The Wandelgek was visiting, owned a bunch of horses and bactrian camels, which they both used as cattle but also to make tours with tourists or travellers with the awesome landscape of the reserve as a backdrop.

Drinking Kumis with Nomads

The Wandelgek entered the family ger and sat down. A ger is not that large and sometimes the families living there are big. To create a bit of structure, there is a specific location in each ger for every family member to sit and to sleep and when everyone is inside, the family members walk clockwise around the stove to avoid a lot of obstructions while moving.

Kumis (also spelled kumiss or koumiss or kumys, see other transliterations and cognate words below under terminology and etymology – Kazakh: қымыз, qymyz) is a fermented dairy product traditionally made from mare’s milk or donkey milk. The drink remains important to the peoples of the Central Asian steppes, of Huno-Bulgar, Turkic and Mongol origin: Kazakhs, Bashkirs, Kalmyks, Kyrgyz, Mongols, and Yakuts. Kumis was historically consumed by the Khitan, Jurchen, Hungarians and Han Chinese of North China as well.

Kumis is a dairy product similar to kefir, but is produced from a liquid starter culture, in contrast to the solid kefir “grains”. Because mare’s milk contains more sugars than cow’s or goat’s milk, when fermented, kumis has a higher, though still mild, alcohol content compared to kefir.

Even in the areas of the world where kumis is popular today, mare’s milk remains a very limited commodity. Industrial-scale production, therefore, generally uses cow’s milk, which is richer in fat and protein, but lower in lactose than the milk from a horse.

Before fermentation, the cow’s milk is fortified in one of several ways. Sucrose may be added to allow a comparable fermentation. Another technique adds modified whey to better approximate the composition of mare’s milk.

Production of mare’s milk

A 1982 source reported 230,000 mares were kept in the Soviet Union specifically for producing milk to make into kumis. Rinchingiin Indra, writing about Mongolian dairying, says “it takes considerable skill to milk a mare” and describes the technique: the milker kneels on one knee, with a pail propped on the other, steadied by a string tied to an arm. One arm is wrapped behind the mare’s rear leg and the other in front. A foal starts the milk flow and is pulled away by another person, but left touching the mare’s side during the entire process.

In Mongolia, the milking season for horses traditionally runs between mid-June and early October. During one season, a mare produces approximately 1,000 to 1,200 litres of milk, of which about half is left to the foals.

Production of kumis

Kumis is made by fermenting raw unpasteurized mare’s milk over the course of hours or days, often while stirring or churning. (The physical agitation has similarities to making butter). During the fermentation, lactobacilli bacteria acidify the milk, and yeasts turn it into a carbonated and mildly alcoholic drink.

Traditionally, this fermentation took place in horse-hide containers, which might be left on the top of a yurt and turned over on occasion, or strapped to a saddle and joggled around over the course of a day’s riding. Today, a wooden vat or plastic barrel may be used in place of the leather container.

In modern controlled production, the initial fermentation takes two to five hours at a temperature of around 27 °C (81 °F); this may be followed by a cooler aging period. The finished product contains between 0.7 and 2.5% alcohol.

Kumis itself has a very low level of alcohol, comparable to small beer, the common drink of medieval Europe that also helps to avoid the consumption of potentially contaminated water. Kumis can, however, be strengthened through freeze distillation, a technique Central Asian nomads are reported to have employed. It can also be made into the distilled beverage known as araka or arkhi.

Kumis consumption

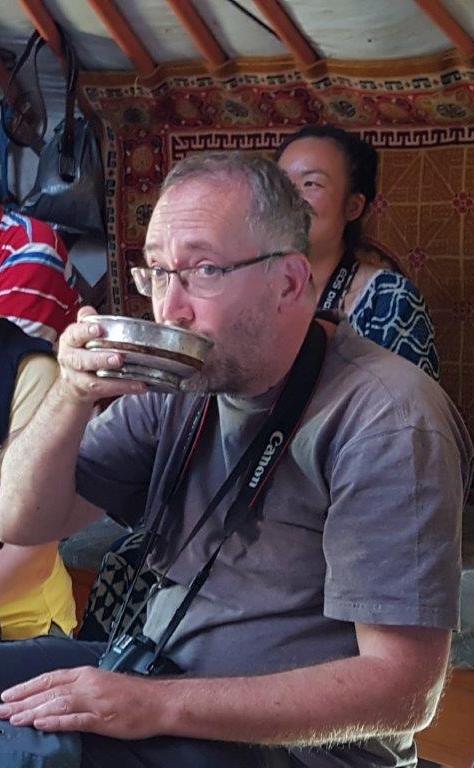

The Wandelgek drank his 1st kumis in Kyrgyzstan on the market of Naryn. That had been very young kumis with almost no alcohol in it and no carbon dioxide either. It tasted good though, like buttermilk. This however was real fermented kumis and the sleight bitterness of the alcohol and the carbon dioxide bubbles were very recognizable. I still love this drink and I think the older more fermented version tastes even better.

Me enjoying a cup of fermented kumis…

Strictly speaking, kumis is in its own category of alcoholic drinks because it is made neither from fruit nor from grain. Technically, it is closer to wine than to beer because the fermentation occurs directly from sugars, as in wine (usually from fruit), as opposed to from starches (usually from grain) converted to sugars by mashing, as in beer. But in terms of experience and traditional manner of consumption, it is much more comparable to beer. It is even milder in alcoholic content than beer. It is arguably the region’s beer equivalent.

Kumis is very light in body compared to most dairy drinks. It has a unique, slightly sour flavor with a bite from the mild alcoholic content. The exact flavor is greatly variable between different producers.

Kumis is usually served cold or chilled. Traditionally it is sipped out of small, handle-less, bowl-shaped cups or saucers, called piyala. The serving of it is an essential part of Kyrgyz hospitality on the jayloo or high pasture, where they keep their herds of animals (horse, cattle, and sheep) during the summer phase of transhumance.

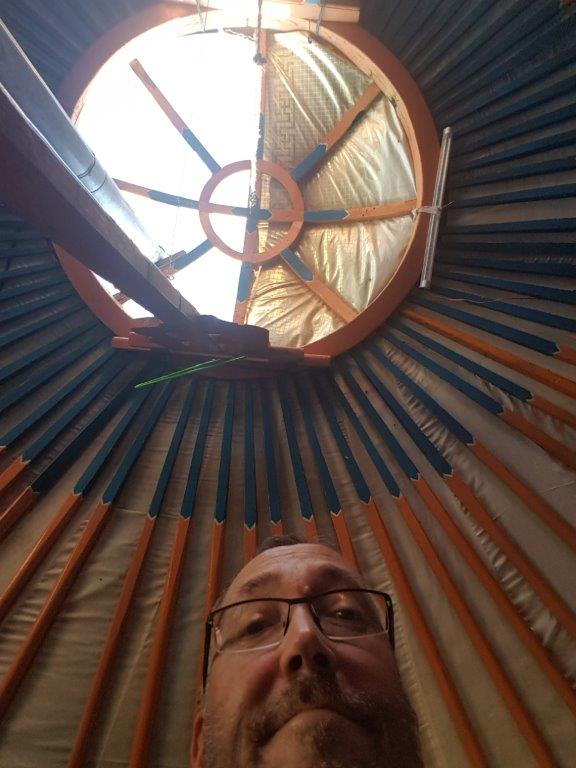

Me after a few drinks of kumis ?

Above my head is the top or crown of the ger (same as in yurts), used for ventilation and as a hole for the stove chimney. This crown is also depicted as a symbol in red on top of a yellow sun on the national flagg of Kyrgyzstan:

Then The Wandelgek said goodbye to the friendly nomads and travelled onwards…