Roadtrip through Central Mongolia

Central Mongolia has these large, wide, green valleys and temperature is higher and more pleasant at the end of Summer or the start of autumn than in northern Mongolia. Central Mongolia is squeezed between the hot and barren Gobi desert in the south and the cold and harshness of Siberia in the north. Weather conditions were extremely pleasant when The Wandelgek visited the area. Temperatures in Siberia had been around 15 degrees Celsius, in northern Siberia these had gone up to 18 to 20 Celsius, but here in Central Siberia they were between 20 and 25 Celsius.

The next part of this Mongolian roadtrip led through central Mongolia returning towards northern Mongolia (or actually an area that administratively and in terms of landscape belongs to the more rugged, mountainous northern Mongolia, but climate wise and latitude wise could just as well have been Central Mongolia (Maybe it’s time to add a more detailed map of my roadtrip??)) and going back Into the Wild.

1st the bus drove through the enormous valley where Karakorum and Erdene Zuu were located. The hills or mountains bordering the valley were so far away that they could hardly be seen. This was how I had imagined that Mongolia would be before I visited. Large plains full of grass and an occasional horse or a ger.

The Wandelgek boarded the bus and it drove towards the modern city of Kharkorin, which was built next to the ancient remains of Karakorum. Kharkorin had just like most modern Mongolic cities or villages, an area with brick houses, but it had a rather small area where people lived in gers (compared to other towns. On the plots where the brick buildings stood, were also gers and because The Wandelgek could not imagine that the owners of a brick house would live in a ger in their backyard, he imagined that these gers were most likely tourist/traveller accommodation for those visiting Erdene Zuu monastery or Karakorum or for those passing through to travel further west.

It was past noon as we stopped for lunch at a restaurant in Kharkorin…

Kharkorin had a supermarket and it was due time to refill stocks, before going into the wild again for a couple of days.

However, The Wandelgek felt he did not need anything from the supermarket, so he took this opportunity to explore this typical Mongolian village. The area opposite of the supermarket was a market area.

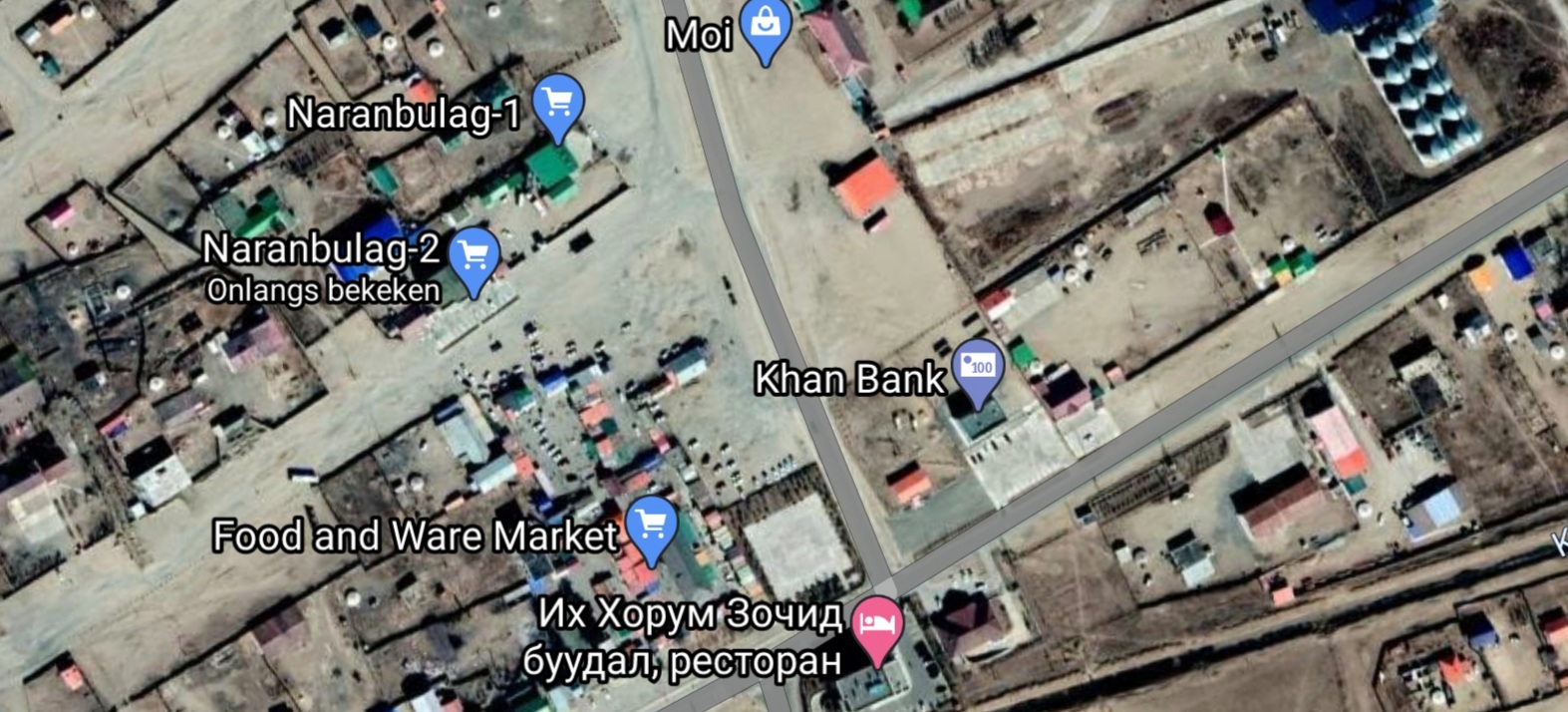

The dark blue roofed building is the Supermarket. In front of it, across the dirtroad, is the market area. A bit to the left is a small black diagonal shade(at the letter a of and in Food and Ware market), that is the tower. To the right across the mainroad (right top corner of the pic) are the tanks visible on a picture probably filled with oil, petrol or gasoline.

A bit abandoned though cause all stalls were cleared and all shops except maybe for one or two had closed their doors. Most of the shops were containers some were like tiny houses or sheds in which market stall materials and goods were stored.

There was this giant storage facility, probably for petrol, gasoline or maybe oil…

This wall was decorated with the Tibetan Buddhist endless knot, a symbol for the eternal of life.

The endless or eternal knot

The endless knot or eternal knot (Tibetan དཔལ་བེའུ། dpal be’u; Mongolian Түмэн өлзий) is a symbolic knot and one of the Eight Auspicious Symbols. It is an important symbol in both Jainism and Buddhism. It is an important cultural marker in places significantly influenced by Tibetan Buddhism such as Tibet, Mongolia, Tuva, Kalmykia, and Buryatia. It is also found in Celtic and Chinese symbolism.

Origin

The endless knot symbol appears on clay tablets from the Indus Valley Civilization (2500 BC), and the same symbol also appears on a historic era inscription.

Interpretation in Tibetan Buddhism:

The endless knot iconography symbolised Samsara i.e., the endless cycle of suffering or birth, death and rebirth within Tibetan Buddhism.

Next to the supermarket was the statue of a goats, a sheep, a cow, a camel and a horse, all animals that were used as livestock by nomads.

A bit further down the dirtroad was this metal tower of which I do not know its function. It looked like an unfinished tower or maybe it was a work of art?

Next The Wandelgek walked through a residential area which was a total mix of styles and of old and new houses. The blueish house with the descending rooftop was new and there were people working to finish the building. Some building were empty and seemed unfinished. Something The Wandelgek would see much more in the next days. Mongolians often start building on a project and then abandon it when the money to finish the building runs out.

After a while The Wandelgek returned to the supermarket and the bus, to finish the last long stretch of the day.

The Orkhon valley

1st the bus drove through the enormous valley where Karakorum and Erdene Zuu were located. The hills or mountains bordering the valley were so far away that they could hardly be seen. This was how I had imagined that Mongolia would be before I visited. Large plains full of grass and an occasional horse or a ger.

Orkhon Valley Cultural sprawls along the banks of the Orkhon River in Central Mongolia, some 320 km west from the capital Ulaanbaatar. It was inscribed by UNESCO in the World Heritage List as representing the development of nomadic pastoral traditions spanning more than two millennia.

For many centuries, the Orkhon Valley was viewed as the seat of the imperial power of the steppes. The first evidence comes from a stone stele with runic inscriptions, which was erected in the valley by Bilge Khan, an 8th-century ruler of the Göktürk Empire. Some 25 miles to the north of the stele, in the shadow of the sacred forest-mountain Ötüken, was his Ördü, or nomadic capital. During the Qidan domination of the valley, the stele was reinscribed in three languages, so as to record the deeds of a Qidan potentate.

Mountains were considered sacred in Tengriism as an axis mundi, but Ötüken was especially sacred because the ancestor spirits of the khagans and beys resided here. Moreover, a force called qut was believed to emanate from this mountain, granting the khagan the divine right to rule the Turkic tribes. Whoever controlled this valley was considered heavenly appointed leader of the Turks and could rally the tribes. Thus control of the Orkhon Valley was of the utmost strategic importance for every Turkic state. Historically every Turkic capital (Ördü) was located here for this exact reason. There were many houses by the bank but they are all gone now.

Gradually the landscape was changing as we re-entered northern Mongolia. There were more hills and the land had more elevations, meaning that the road went more up and down.

The final destination for today was almost reached and I’ll write more about that in my next upcoming blogpost.