37. Greenland: The Museum in Qeqertarsuaq

The plan was to leave Qeqertarsuaq and Disko Island early in the morning and board the ferry boat at the Whale Cheekbone gate in the harbor, but the weather had other plans.

There was a heavy storm wind blowing over Disko Bay, and although it was sunny and the sky was blue, this cold and harsh wind caused the water to create large waves. There had been boats coming from Ilulissat, but I heard the captain say that he should have never left the harbor. It had been a wild and dangerous boat trip to get to Qeqertarssuaq and he now refused to leave for Aasiaat. He announced that he would re assess the situation and weather conditions at noon and see whether it was possible to leave for Aasiaat then.

On the harbor quay were some old cannons…

This meant spare time in Qeqertarssuaq. Conditions for a walk were to bad with this wind but there was a museum near the harbor. The Wandelgek decided to visit this.

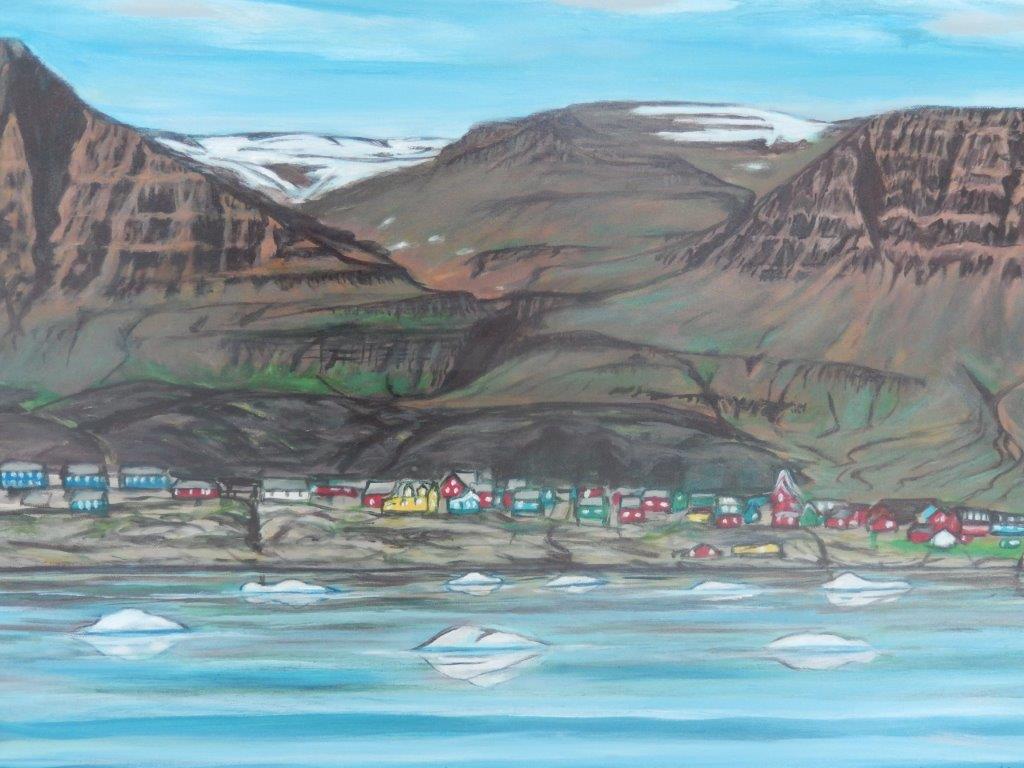

Museum of Qeqertarsuaq

The museum describes everyday life during the colonial period, when the colony ‘Godhavn’ held a powerful position.

The colony was the principal town in North Greenland and a key location for whaling and trade.

The museum was quite similar to that in Ilulissat, but there was one major difference. There was a cold room added to this museum, which was a separate barn with no heating in which several old hunting and travelling materials/items, used by the Inuit were exhibited.

Traces of settlement between five and six thousand years ago have been found at Qeqertarsuaq. The settlers were paleo-Eskimos wandering south.

During the 18th century, the first whalers came to Qeqertarsuaq, where they found a suitable anchorage. The town was founded as Godhavn by the whaler Svend Sandgreen in 1773. The name was sometimes anglicized as Guthaven and the settlement was also known as Lievely or Leifly. It served as the northernmost point in the enforcement of the Danish rights to whaling in the region. Whaling has been of great importance to the town over the past two centuries. Hunting and fishing are still the primary occupations for the island’s inhabitants.

Kayaking

Below are 2 pics of a kayak model and one of an umiaq (women boat) model.

A series of pics of Inuit kayaking while hunting whales or other sea mammals…

A new microscopic species has been discovered in the hotsprings of Disko Island…

Year around trek of the whales…

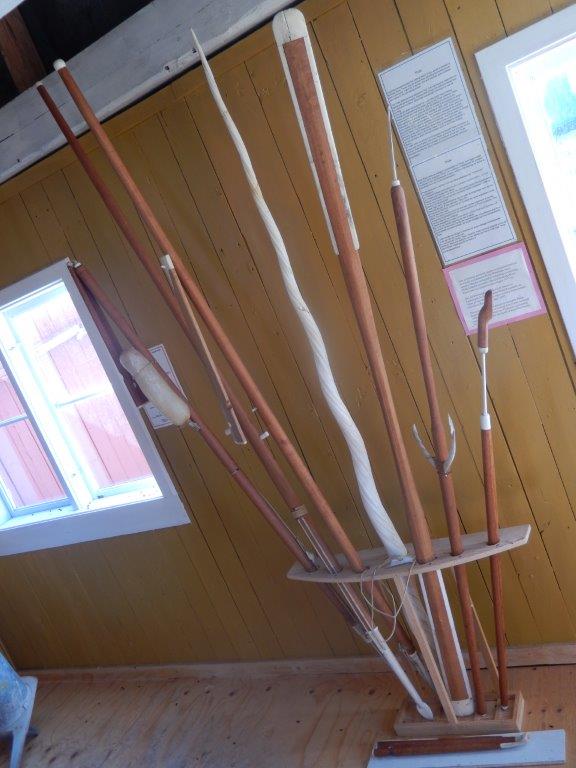

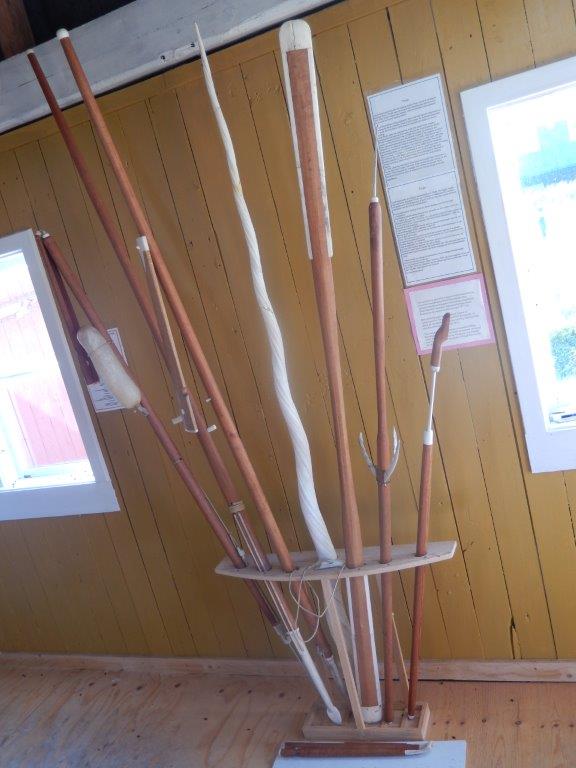

In the shed next to the main building was a large collection of kayaks, dogsleds and harpoons…

Kayaks

These are old kayaks, preserved in a cold climate inside. Some kayaks were stored upon the wooden ceiling beams…

Dogsleds

Some for these ancient dogsleds…

Harpoons

Then there was also a collection of different harpoons used in whale hunting…

Some harpoons come with a throwing mechanism, a small piece of wood to which the harpoon is attached. This piece of wood is used to throw the harpoon with more power.

The Narwhal (Narwhale)

The narwhal (Monodon monoceros), or narwhale, is a medium-sized toothed whale that possesses a large “tusk” from a protruding canine tooth. It lives year-round in the Arctic waters around Greenland, Canada, and Russia. It is one of two living species of whale in the family Monodontidae, along with the beluga whale. The narwhal males are distinguished by a long, straight, helical tusk, which is an elongated upper left canine. The narwhal was one of many species described by Carl Linnaeus in his publication Systema Naturae in 1758.

Like the beluga, narwhals are medium-sized whales. For both sexes, excluding the male’s tusk, the total body size can range from 3.95 to 5.5 m (13 to 18 ft); the males are slightly larger than the females. The average weight of an adult narwhal is 800 to 1,600 kg (1,760 to 3,530 lb). At around 11 to 13 years old, the males become sexually mature; females become sexually mature at about 5 to 8 years old. Narwhals do not have a dorsal fin, and their neck vertebrae are jointed like those of most other mammals, not fused as in dolphins and most whales.

Found primarily in Canadian Arctic and Greenlandic and Russian waters, the narwhal is a uniquely specialized Arctic predator. In winter, it feeds on benthic prey, mostly flatfish, under dense pack ice. During the summer, narwhals eat mostly Arctic cod and Greenland halibut, with other fish such as polar cod making up the remainder of their diet. Each year, they migrate from bays into the ocean as summer comes. In the winter, the male narwhals occasionally dive up to 1,500 m (4,920 ft) in depth, with dives lasting up to 25 minutes. Narwhals, like most toothed whales, communicate with “clicks”, “whistles”, and “knocks”.

Narwhals can live up to 50 years. They are often killed by suffocation after being trapped due to the formation of sea ice. Other causes of death, specifically among young whales, are starvation and predation by orcas. As previous estimates of the world narwhal population were below 50,000, narwhals are categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as Nearly Threatened. More recent estimates list higher populations (upwards of 170,000), thus lowering the status to Least Concern. Narwhals have been harvested for hundreds of years by Inuit people in northern Canada and Greenland for meat and ivory, and a regulated subsistence hunt continues.

The tusk(s)

The most conspicuous characteristic of the male narwhal is a single long tusk, which is in fact a canine tooth that projects from the left side of the upper jaw, through the lip, and forms a left-handed helix spiral. The tusk grows throughout life, reaching a length of about 1.5 to 3.1 m (4.9 to 10.2 ft). It is hollow and weighs around 10 kg (22 lb). About one in 500 males has two tusks, occurring when the right canine also grows out through the lip. Only about 15 percent of females grow a tusk which typically is smaller than a male tusk, with a less noticeable spiral. Collected in 1684, there is only one known case of a female growing a second tusk.

Scientists have long speculated on the biological function of the tusk. Proposed functions include use of the tusk as a weapon, for opening breathing holes in sea ice, in feeding, as an acoustic organ, and as a secondary sex character. The leading theory has long been that the narwhal tusk serves as a secondary sex character of males, for nonviolent assessment of hierarchical status on the basis of relative tusk size. However, detailed analysis reveals that the tusk is a highly innervated sensory organ with millions of nerve endings connecting seawater stimuli in the external ocean environment with the brain. The rubbing of tusks together by male narwhals is thought to be a method of communicating information about characteristics of the water each has traveled through, rather than the previously assumed posturing display of aggressive male-to-male rivalry. In August 2016, drone videos of narwhals surface-feeding in Tremblay Sound, Nunavut showed that the tusk was used to tap and stun small Arctic cod, making them easier to catch for feeding. It’s important to note, however, that the tusk can not serve a critical function for narwhals’ survival because females, who generally do not have tusks, still manage to live longer than males and occur in the same areas. Therefore, the general scientific consensus is that the narwhal tusk is a sexual trait, much like the antlers of a stag, the mane of a lion, or the feathers of a peacock.

Vestigial teeth

The tusks are surrounded posteriorly, ventrally, and laterally by several small vestigial teeth which vary in morphology and histology. These teeth can sometimes be extruded from the bone, but mainly reside inside open tooth sockets in the narwhal’s snout alongside the tusks. The varied morphology and anatomy of small teeth indicate a path of evolutionary obsolescence, leaving the narwhal’s mouth toothless.

The harpoon that struck me most, was the white tooth of a Narwhal. Hunters use the Narwhal tooth to kill Narwhals.

Some more history of Godhavn/Qeqertarsuaq

From an early date, Godhavn shared the administration of Greenland with Godthåb (modern Nuuk). Godhavn served as the capital for North Greenland while Godthåb directed South Greenland. In 1862, a new law on municipalities was passed and the so-called Directions were introduced in Greenland. The primary task of the Directions was the administration of the means set apart for social purposes: support for widows, orphans, and others in need. The Directions also functioned as inferior courts in case of theft and other petty crimes. The Directions also took active part in the fight against the spreading of distemper. In Godhavn, they founded a kayak school for boys and a sewing school for girls.

The Councils of Northern and Southern Greenland were summoned to a meeting in Godhavn on 3 May 1940. Following this meeting, administration for the entire island was concentrated in Godthåb. The Chief Administrative Office was abolished in 1950 at the establishment of the National Council of Greenland. With the end of government positions in town, the local economy focused more directly on hunting and fishing.

On 1 January 2009, the former Qeqertarsuaq municipality was merged into the new Qaasuitsup municipality. This in turn was partitioned on 1 January 2018, at which time Qeqertarsuaq became part of the new municipality of Qeqertalik.

After leaving the museum The Wandelgek returned to the harbor hoping the ferry boats would leave for Aasiaat, but there was little hope. The wind had not lessened in power…