The NOMAD way – photo essay

Nomads… A certain mystical ring is connected with this word. We imagine, sturdy weather hardened faces, strong sun burned bodies of people used to live an at least physically hard life in some empty desert, grass plain, mountainous region or even icy tundra, following cattle or hunting for wildlife to survive. Survival is another word that we might find synonymous with their way of life. Yes that life style is a hard one, but we can’t help admiring that and some of us even long for the freedom or better the independence from mass consumption, living in a harmonious way with Nature and the absence of materialistic desires that come with it. Nowadays I even hear people proposing our capitalistic and consumptive society should be reformed into a more sustainable society and nomad “societies” do get mentioned as examples of a possible direction. The modern Digital Nomad is perhaps the most blatant example of humans striving for that life style.

Without judging about the above, I thought it a good idea to delve into my memories of experiences and numerous pictures, collected while travelling to try and tell a (photo)story about what it looks like to be a real Nomad.

The Wandelgek has travelled the World for many many years and during these travels which became more and more travels towards the frontiers of this world where tourism is absent or just starting to get a bit of foot on the ground, he met many nomads, roaming around, mostly following herds of cattle.

This is an account of many meetings with nomadic tribes and a description of some of their customs.

But 1st: What is a Nomad?

A nomad is a member of a community of people without fixed habitation who regularly move to and from the same areas, including nomadic hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), and tinker or trader nomads. As of 1995, there were an estimated 30–40 million nomads in the world.

Nomadic hunting and gathering, following seasonally available wild plants and game, is by far the oldest human subsistence method. Pastoralists raise herds, driving them, or moving with them, in patterns that normally avoid depleting pastures beyond their ability to recover.

Nomadism is also a lifestyle adapted to infertile regions such as steppe, tundra, or ice and sand, where mobility is the most efficient strategy for exploiting scarce resources. For example, many groups in the tundra are reindeer herders and are semi-nomadic, following forage for their animals.

Sometimes also described as “nomadic” are the various itinerant populations who move about in densely populated areas living not on natural resources, but by offering services (craft or trade) to the resident population. These groups are known as “peripatetic nomads”.

The nomad lifestyle is not a lifestyle often found in Western 1st world countries although there are exceptions on that rule. E.g. the Romani people that nowadays live in Europe and which we also know as Gypsies.

But the Gypsy/Nomadic lifestyle led to quite some conflict with settlers and most nomads have now moved to the verges of the inhabited world and even far beyond to places that could be called hostile to human life.

The Wandelgek’s travels have become more and more focussed towards that type of societies living in that type of more or less hostile and thus quite empty areas of our planet, because they lack most of the diseases and faults that come with prosperity and wealth. Industrial pollution, Plastic waste, mass tourist infrastructure, light pollution, destruction of biodiversity and the creation of a human oriented concrete jungle.

Non of those are present in Nomad societies. They come exclusively with settlers, agricultural and industrial societies.

Are nomads living a pastoral, ideal, peaceful and extremely healthy life? No, certainly not. Let’s not demonize Western society or idealize nomadic society. Both have their advantages and disadvantages, although a Nomadic society does put less of a strain on Mother Nature and its resources.

Travels

The Wandelgek roamed the outbacks, the last frontiers, the edges of our world searching for unspoiled nature and cultures and met with many members of nomadic tribes.

For The Wandelgek personally, nomads are the ultimate walkers, hikers, trekkers. No one can beat those distances crossed. They carry their home like a turtle or a snail to wherever their cattle leads them or wherever the hunting is succesful or the soil rich enough for them to harvest. This makes conversation with nomads very interesting. What makes them decide to move? Which events make them change directions? What “natural landmarks” or stars do they navigate on in an empty desert? How do they find water where there seems to be none? What do they discuss with nomads they encounter? There are so many questions to ask…

The tribes

North Sweden (Lapland)

Sami

At the other side of the lake below is a small Sami summer settlement…

The Sámi people (also spelled Sami or Saami) are an indigenous Finno-Ugric people inhabiting Sápmi, which today encompasses large northern parts of Norway and Sweden, northern parts of Finland, and the Kola Peninsula within the Murmansk Oblast of Russia. The Sámi have historically been known in English as Lapps or Laplanders. Sámi ancestral lands are not well-defined. Their traditional languages are the Sámi languages and are classified as a branch of the Uralic language family.

The Sámi people (also spelled Sami or Saami) are an indigenous Finno-Ugric people inhabiting Sápmi, which today encompasses large northern parts of Norway and Sweden, northern parts of Finland, and the Kola Peninsula within the Murmansk Oblast of Russia. The Sámi have historically been known in English as Lapps or Laplanders. Sámi ancestral lands are not well-defined. Their traditional languages are the Sámi languages and are classified as a branch of the Uralic language family.

Traditionally, the Sámi have pursued a variety of livelihoods, including coastal fishing, fur trapping, and sheep herding. Their best-known means of livelihood is semi-nomadic reindeer herding. Currently about 10% of the Sámi are connected to reindeer herding, providing them with meat, fur, and transportation. 2,800 Sámi people are actively involved in reindeer herding on a full-time basis. For traditional, environmental, cultural, and political reasons, reindeer herding is legally reserved for only Sámi people in some regions of the Nordic countries.

It was in 1993 that The Wandelgek travelled to Lapland or North Sweden to hike the Kungsleden trail, when he 1st got a taste of a real wild nomadic tribe, living in a mountainous and tundra landscape, which means long cold, white and dark winters and short, mosquito infested, wet summers with reasonably pleasant temperatures. The Sami (as the Lap people are really named) are mostly keeping reindeer and the reindeer provides them with almost everything they need. They follow the reindeer trek. Or should I say they used to follow the reindeer trek, because nowadays they have the help of choppers to find their herds.

South West China (Tibet)

Khampa

Kham is a historical region of Tibet covering a land area largely divided between present-day Tibet Autonomous Region and Sichuan, with smaller portions located within Qinghai, Gansu and Yunnan provinces of China. During the Republic of China’s rule over mainland China (1911–1949), most of the region was administratively part of Hsikang. It held the status of “special administrative district” until 1939, when it became an official Chinese province. Its provincial status was nominal and without much cohesion, like most of China’s territory during the time of Japanese invasion and civil war. The natives of the Kham region are called Khampas.

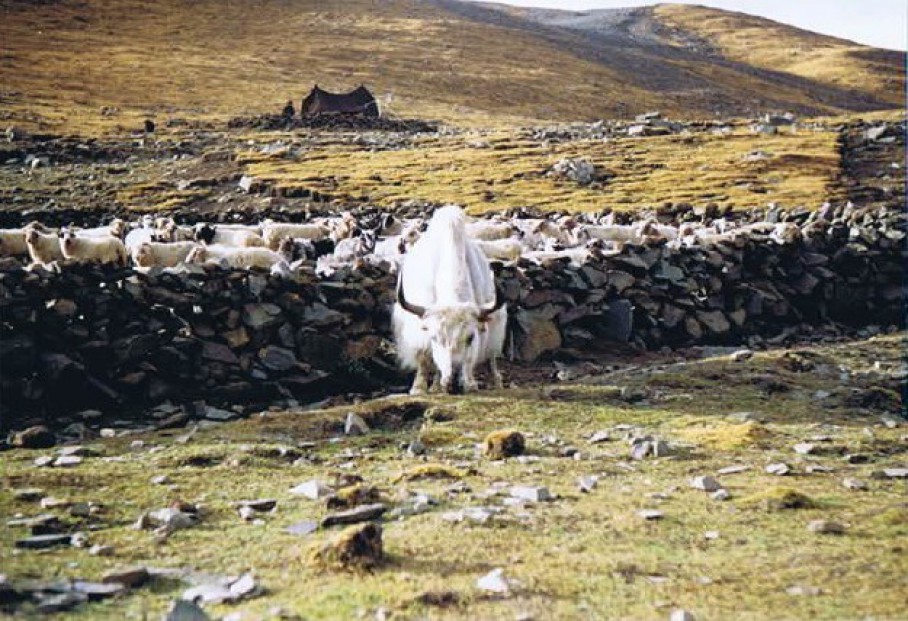

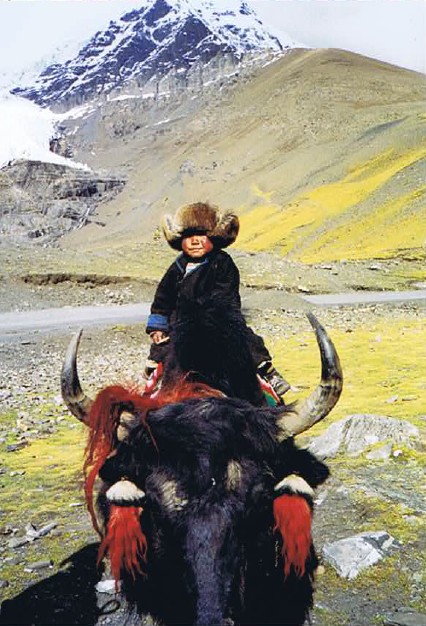

The Khampas mainly live from Yaks, but they herd sheep too. The Yak however provides bones, horns, skin, milk, butter, etcetera…

The awful yak butter tea is also a product as is the oil from melted yak butter used in oil lamps.

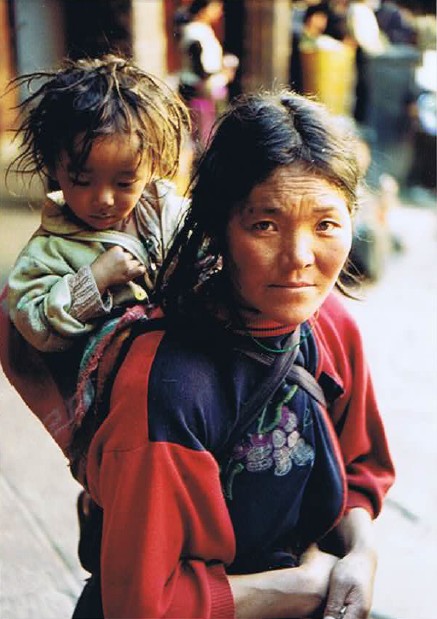

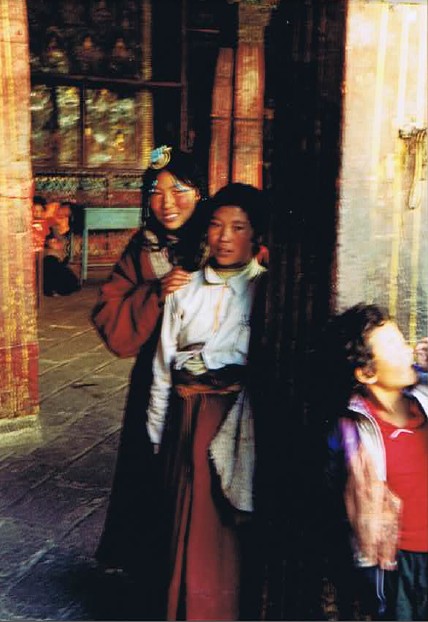

A Tibetan Nomad woman and child in front of their simple tent made of yak skin and bones… The Yak is to the Tibetan nomads what the horse is to Kyrgyz, Kazakh and Mongolian nomads. A yak provides them with meat, fat, oil, bones, skins, fiber/wool, horns and milk. A yak can endure through the very tough Tibetan winter which makes it the ideal livestock animal for nomadic tribes. (Tibet, China, 1999)

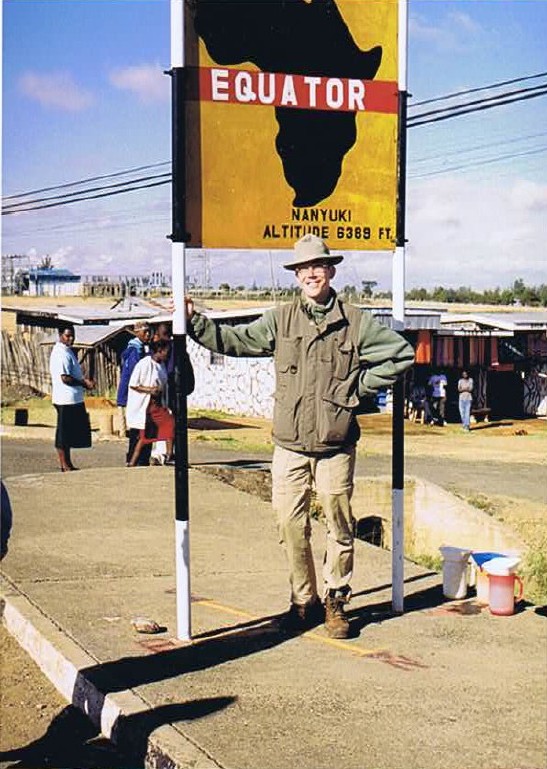

Northern Kenya

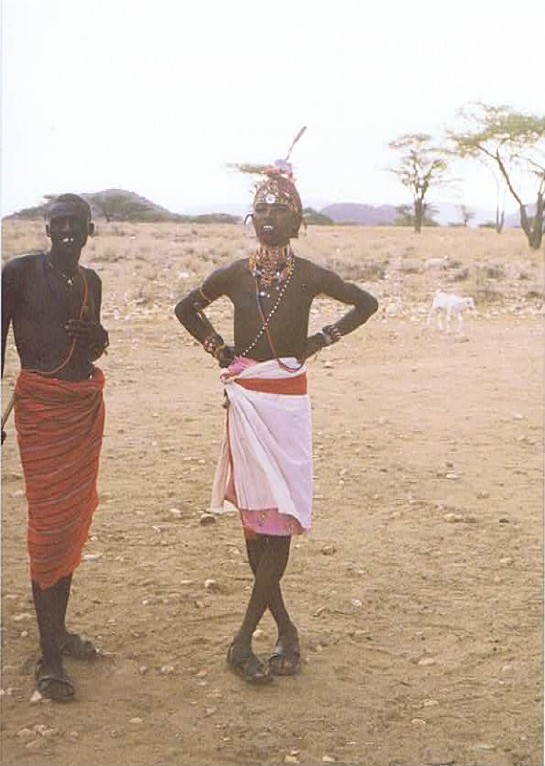

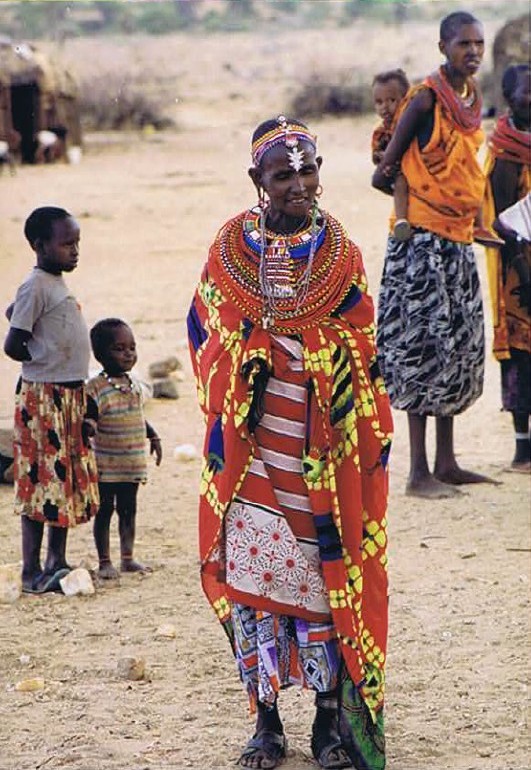

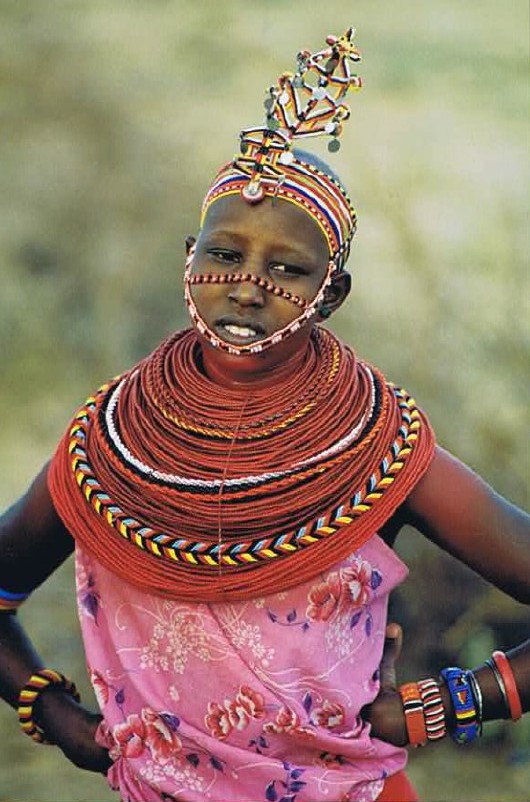

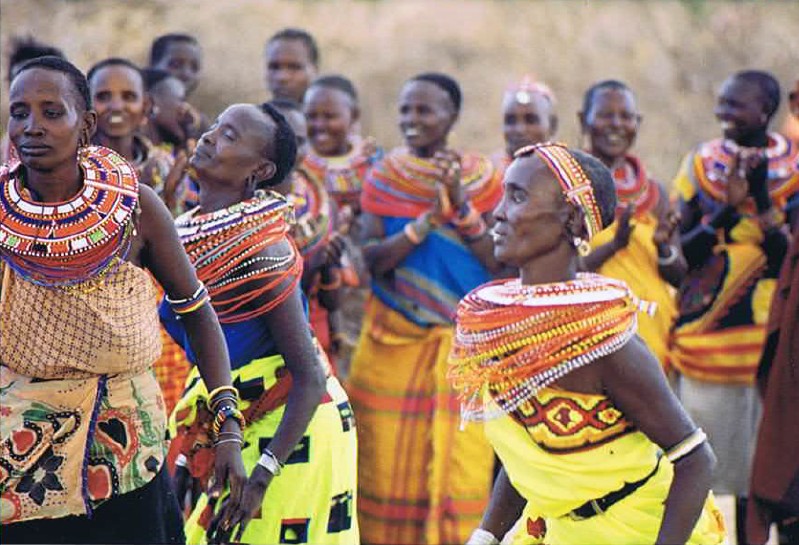

Samburu

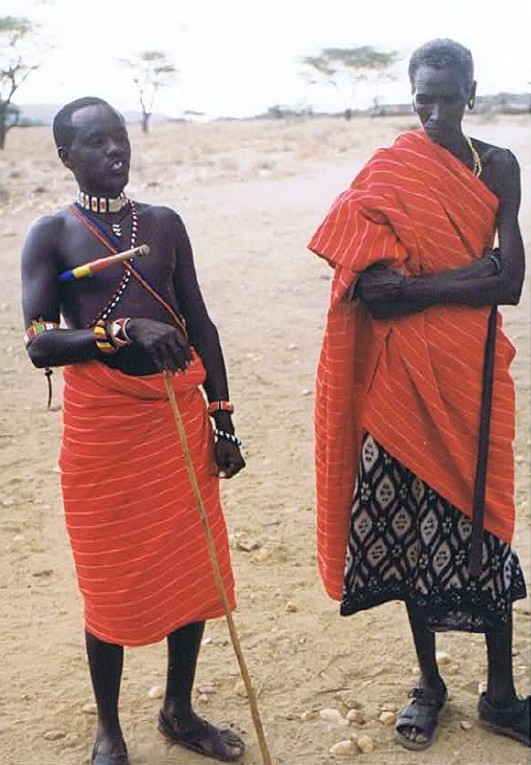

The Samburu are a Nilotic people of north-central Kenya. They are a sub tribe of the Maasai. The Samburu are semi-nomadic pastoralists who herd mainly cattle but also keep sheep, goats and camels. The name they use for themselves is Lokop or Loikop, a term which may have a variety of meanings which Samburu themselves do not agree on. Many assert that it refers to them as “owners of the land” (“lo” refers to ownership, “nkop” is land) though others present a very different interpretation of the term. The Samburu speak the Samburu dialect of the Maa language, which is a Nilo-Saharan language. There are many game parks in the area, one of the most well known is Samburu National Reserve. The Samburu is the third largest in the Maa community of Kenya and Tanzania, after the Kisonko(Isikirari) of Tanzania and Purko of Kenya and Tanzania.

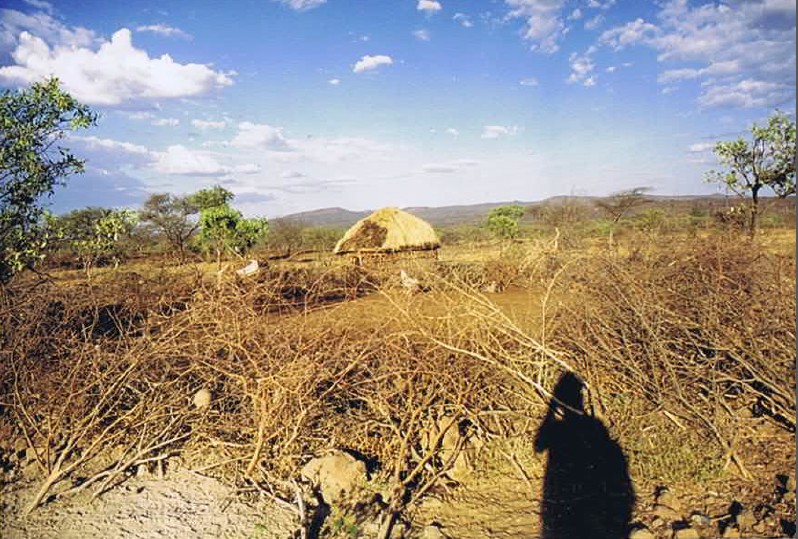

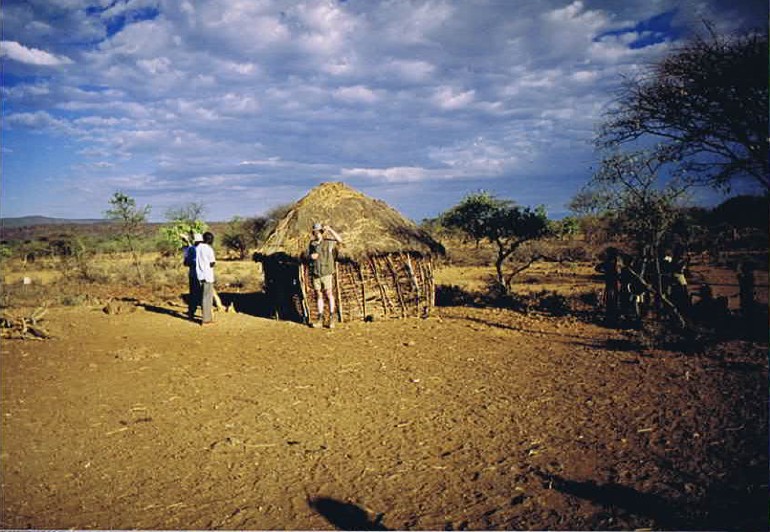

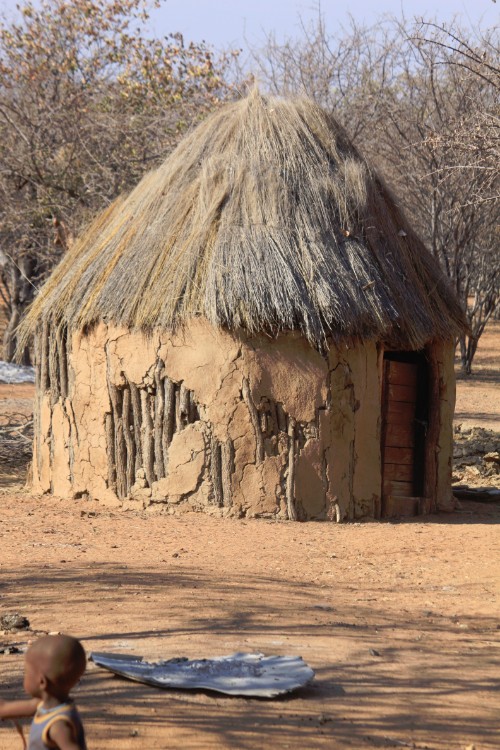

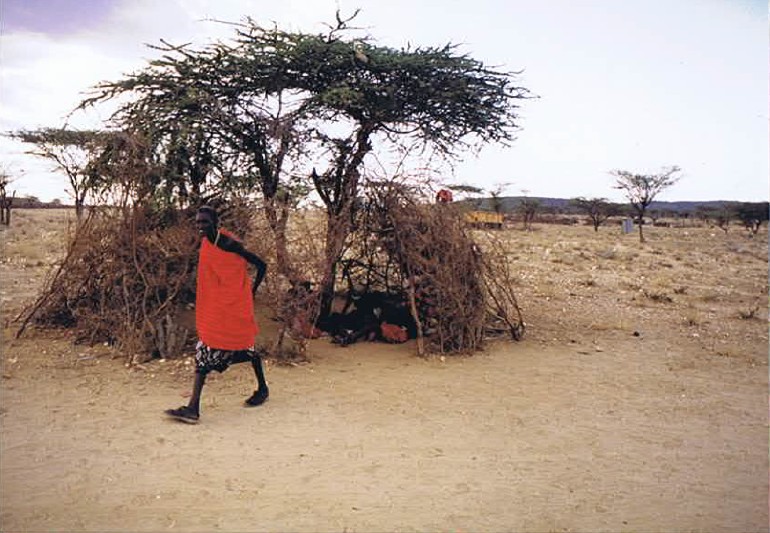

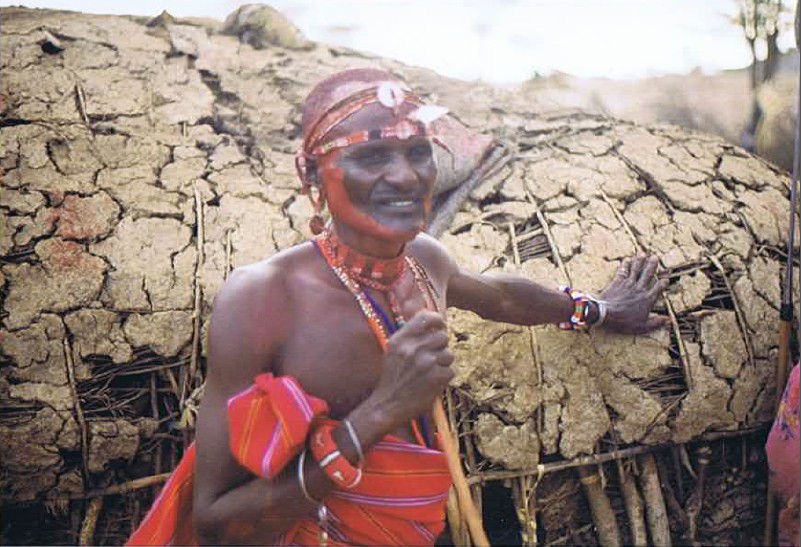

A member of the Samburu nomadic tribe in northern Kenya shows how a hut is created from nothing more than some dry vegetation, dirt and water… actually the whole village was built like that. The surrounding landscape doesn’t offer much more that could be used as building material. ..

A member of the Samburu nomadic tribe in northern Kenya shows how a hut is created from nothing more than some dry vegetation, dirt and water… actually the whole village was built like that. The surrounding landscape doesn’t offer much more that could be used as building material. ..

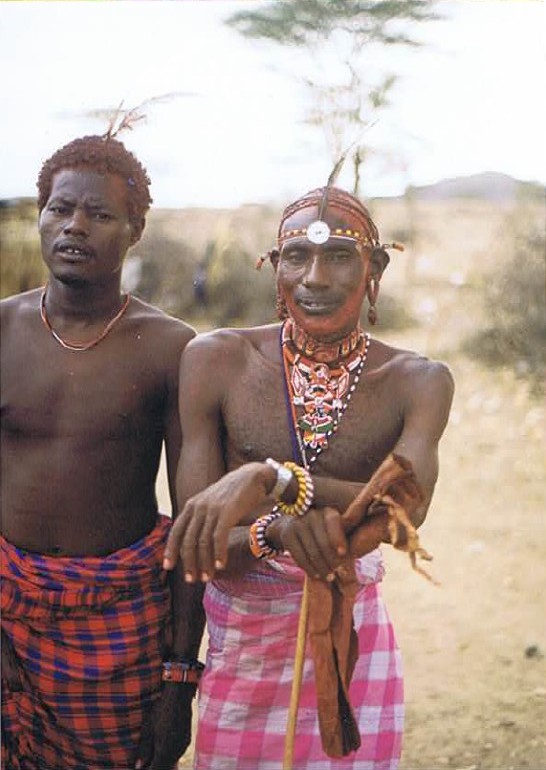

Pokot

The Pokot people (also spelled Pökoot) live in West Pokot County and Baringo County in Kenya and in the Pokot District of the eastern Karamoja region in Uganda. They form a section of the Kalenjin ethnic group and speak the Pökoot language, which is broadly similar to the related Marakwet, Nandi, Tuken and other members of the Kalenjin language group.

Halfway through the nineteenth century, the Pokot expanded their territory rapidly into the lowlands of the Kenyan Rift Valley, mainly at the expense of the Laikipia Maasai people. This was the formation of the plains Pokot, and is captured in their historical narratives.

In that account, when the Pokot nation was forming on the Elgeyo escarpment, the Kerio Valley was occupied by the Samburu. Whenever the Pokot descended into the valley, they were harassed and raided by the Samburu, “Until there arose a wizard among the Pokot who prepared a charm in the form of a stick, which he placed in the Samburu cattle kraals, with the result that all their cattle died”. The Samburu are said to have then left the Kerio Valley and moved to En-ginyang where they formed a large settlement.

Once the Pokot saw that the Kerio Valley was no longer occupied, they descended in large numbers and occupied Tiati and the hills as far south as Ka-ruwon.

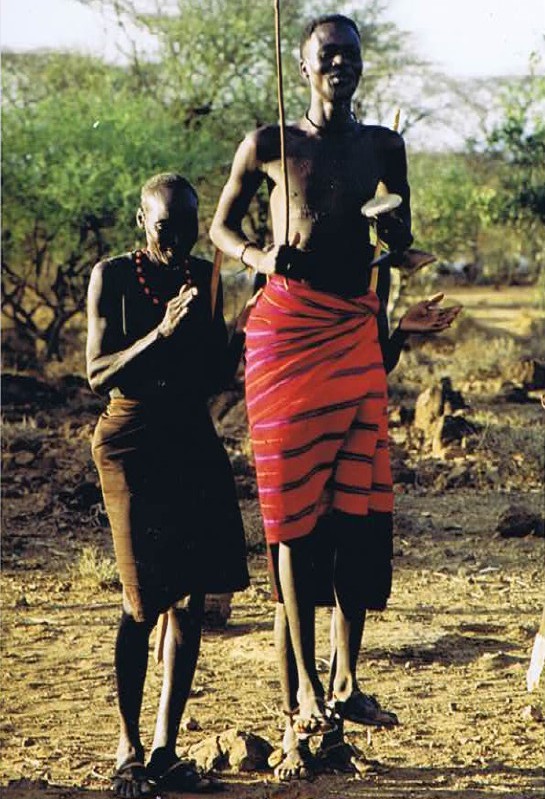

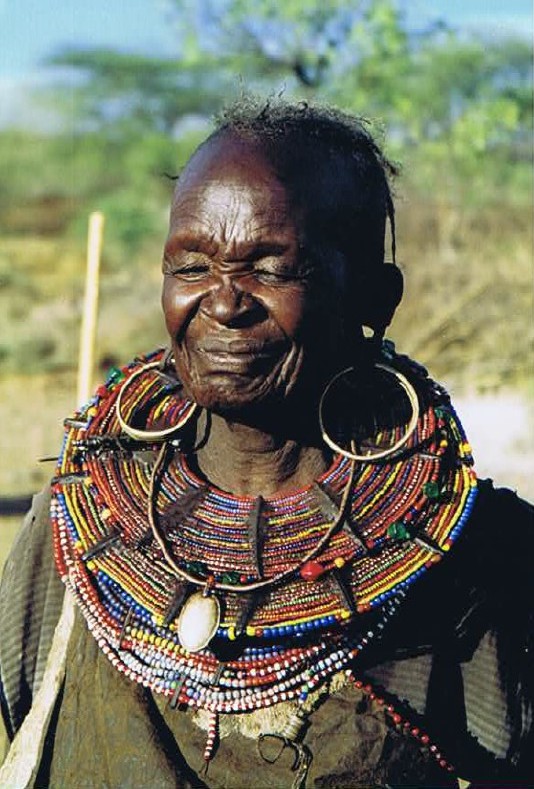

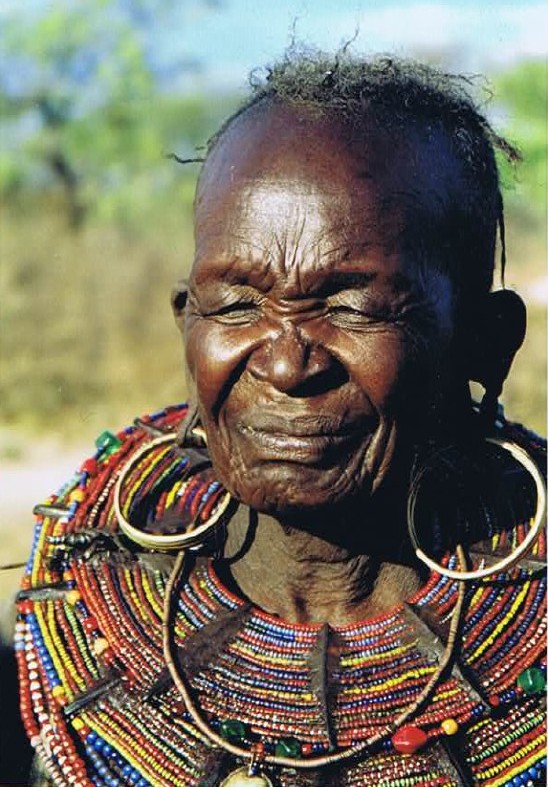

Some of the older members of the Pokot tribe which The Wandelgek visited in 2002 when he visited the Rift valley near Lake Baringo in Kenya.

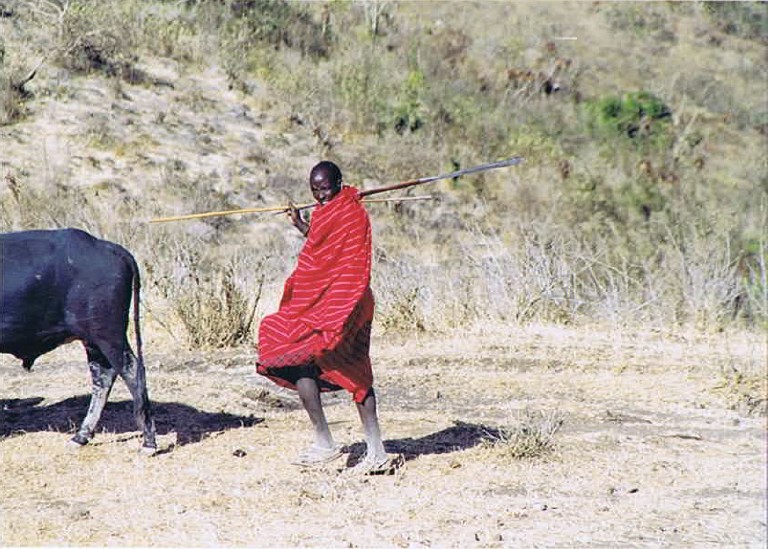

Northern Tanzania

Masai

The Maasai are a Nilotic largest group inhabiting northern, central and southern Kenya and northern Tanzania. They are among the best known local populations internationally due to their residence in towns and villages near the many game parks of the African Great Lakes, and their distinctive customs and dress. The Maasai speak the Maa language (ɔl Maa), a member of the Nilo-Saharan family that is related to the Dinka, Kalenjin and Nuer languages. Many have become educated in the official languages of Kenya and Tanzania, Swahili and English. The Maasai population has been reported as numbering 2,841,622 in Kenya in the 2009 census, compared to 1,377,089 in the 1989 census.

The Tanzanian and Kenyan governments have instituted programs to encourage the Maasai to abandon their traditional lifestyle, but the people have continued their age-old customs. Many Maasai tribes throughout Tanzania and Kenya welcome visits to their towns and villages to experience their culture, traditions, and lifestyle, in return for a fee.

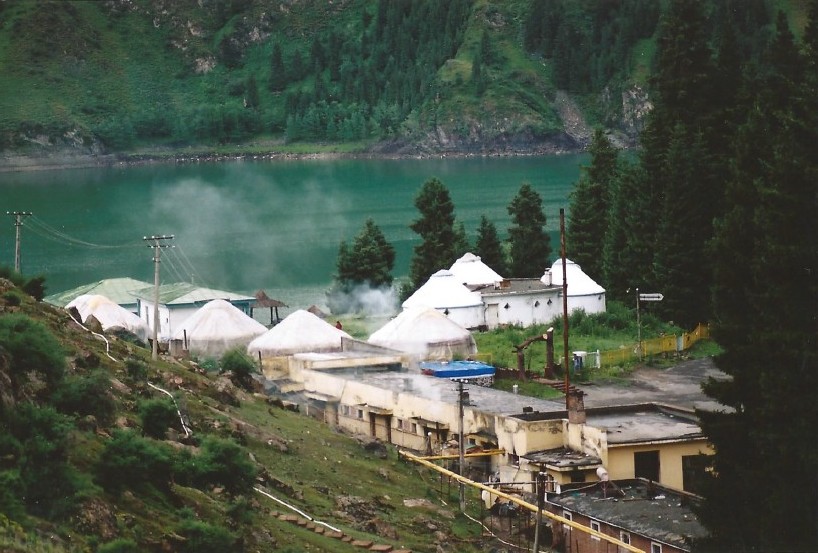

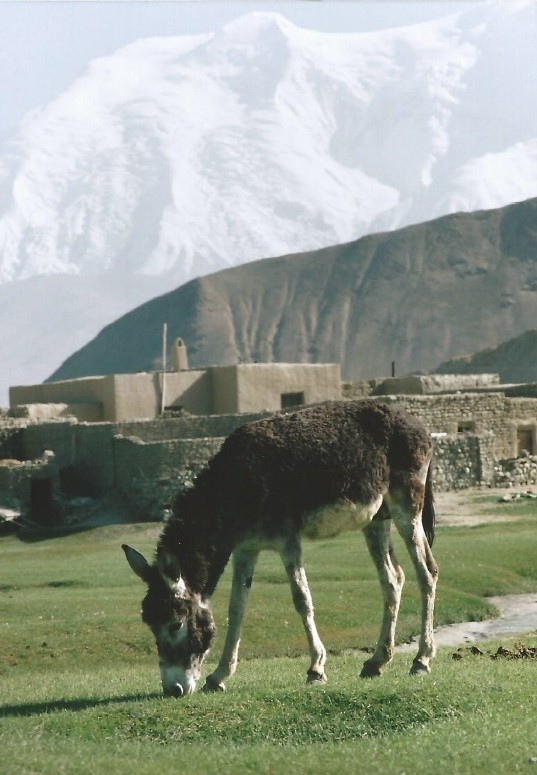

North West China (Xinjiang)

Kazakh

The Kazakhs (also spelled Kazaks, Qazaqs) are a Turkic ethnic group who mainly inhabit the Ural Mountains and northern parts of Central Asia (largely Kazakhstan, but also parts of Russia, Uzbekistan, Mongolia and China), the region also known as the Eurasian sub-continent. Kazakh identity is of medieval origin and was strongly shaped by the foundation of the Kazakh Khanate between 1456 and 1465, when several tribes under the rule of the sultans Zhanibek and Kerey departed from the Khanate of Abu’l-Khayr Khan.

The Kazakhs are descendants of the Turkic and medieval Mongol tribes – Argyns, Dughlats, Naimans, Jalairs, Keraits, Qarluqs and of the Kipchaks.

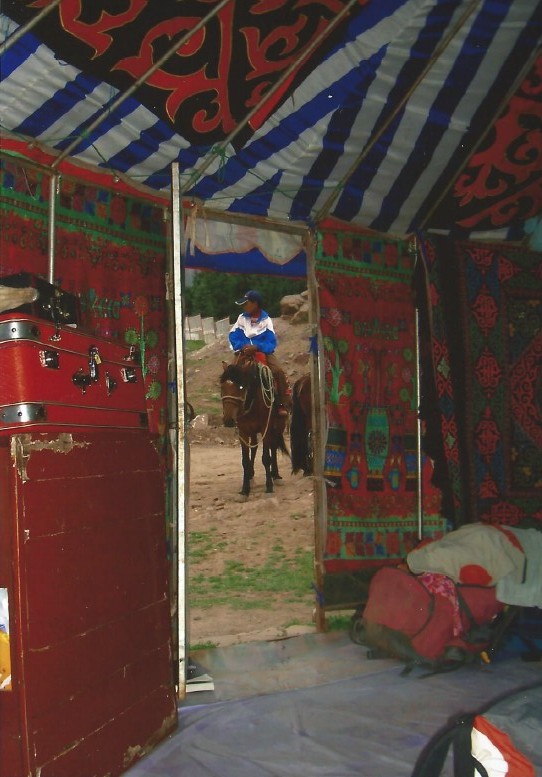

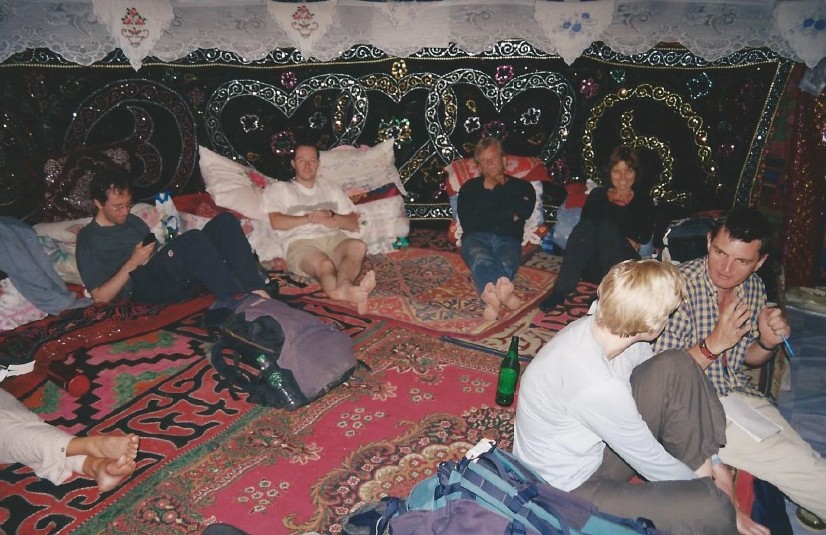

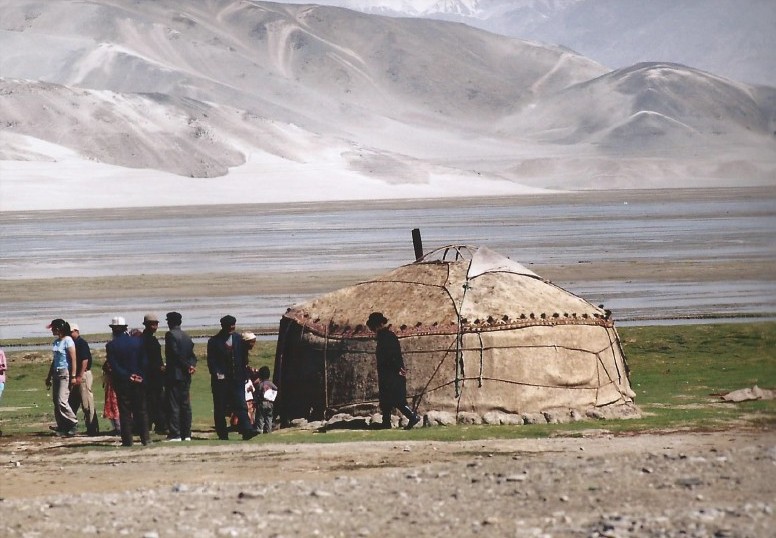

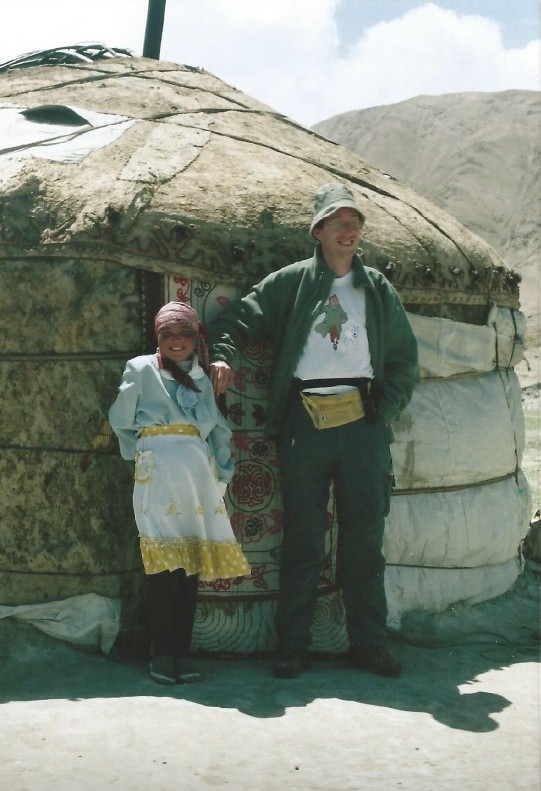

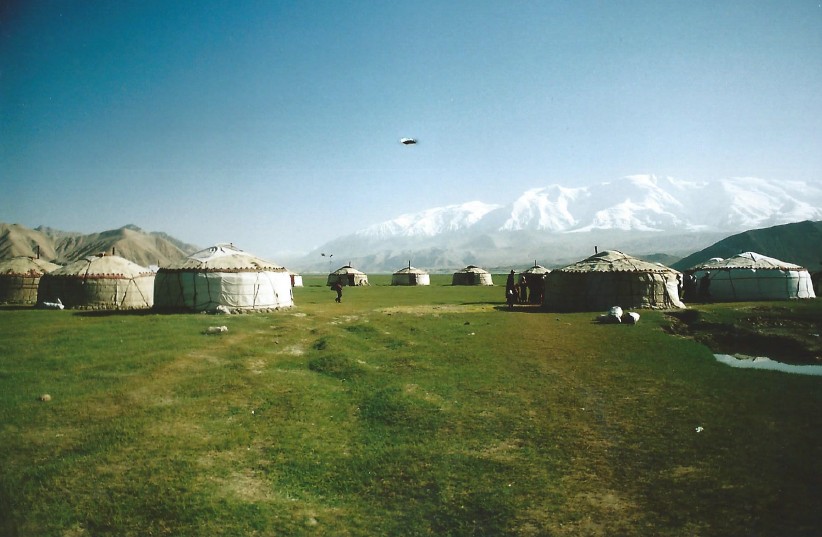

While travelling on the silkroad back in 2004, I slept in yurts as a guest of several Kazakh and Kyrgyz nomads.This enables you to experience nomad day-to-day life. If you have the right equipment (meaning a warm sleeping bag), sleeping in a yurt can be quite comfortable. There is a fire place in the yurt which keeps you from getting cold until the early hours of the morning. Smoke escapes through a hole in the roof and the yurt is rather well isolated because its walls are built in several layers …

(Pamir mountains, China 2004)

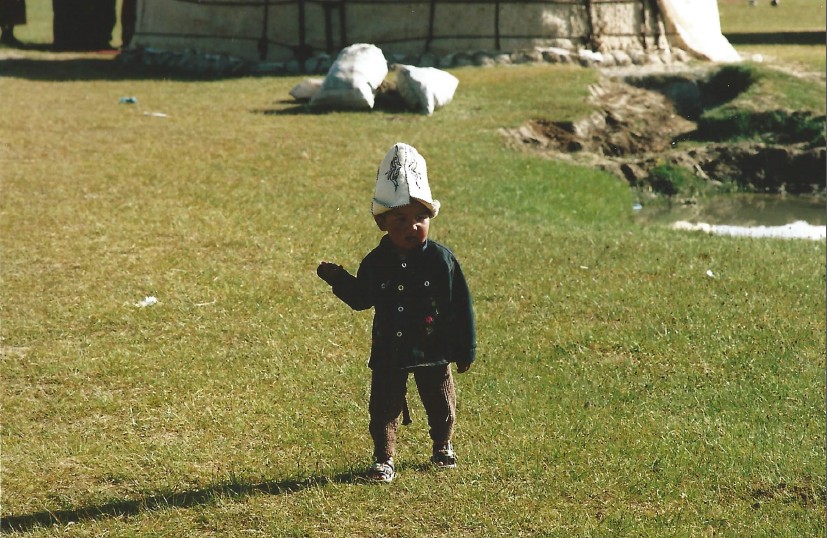

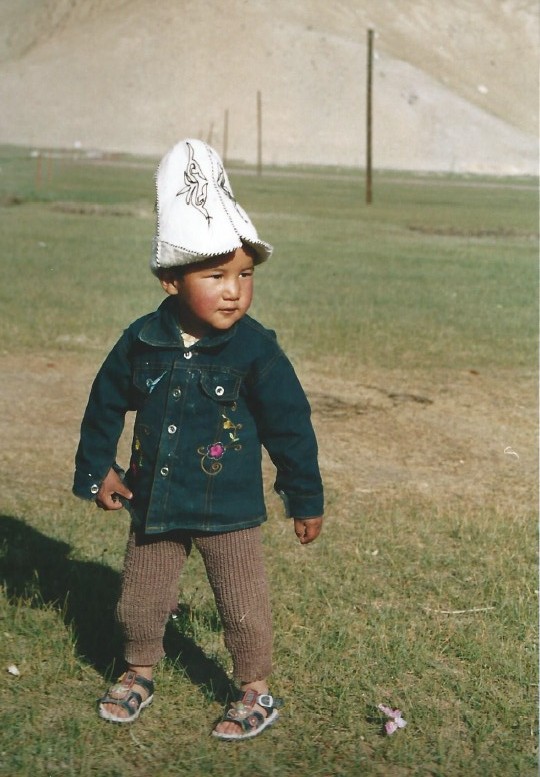

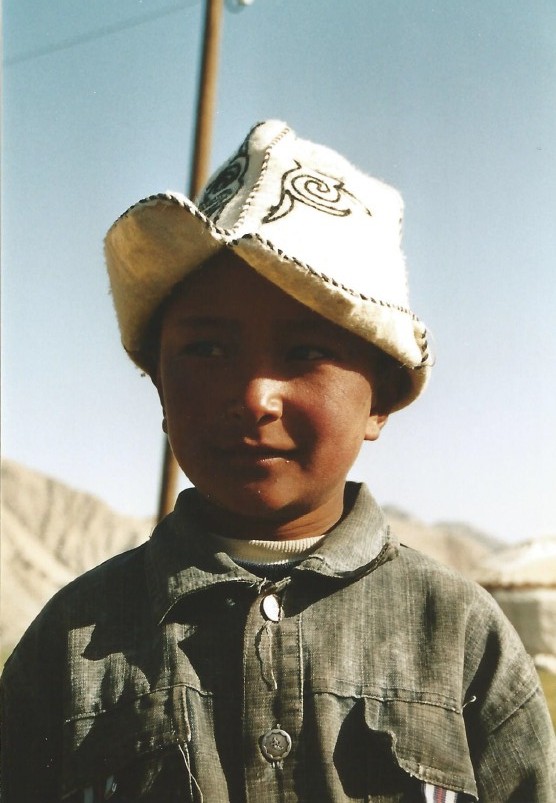

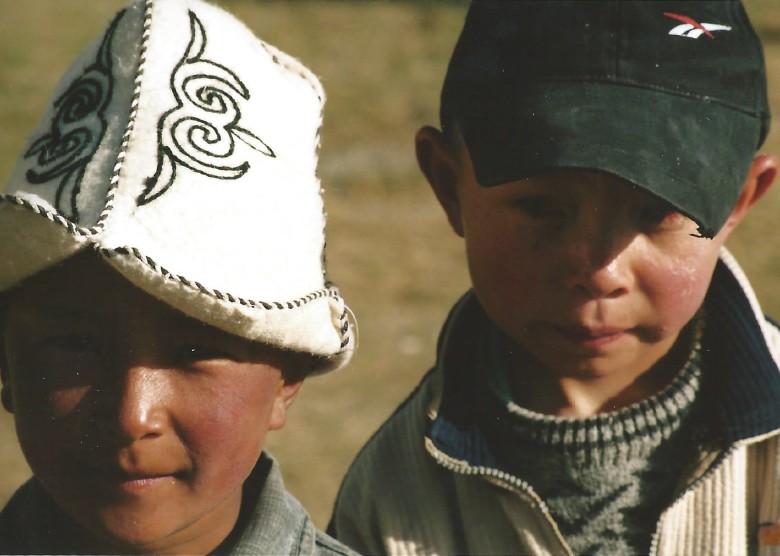

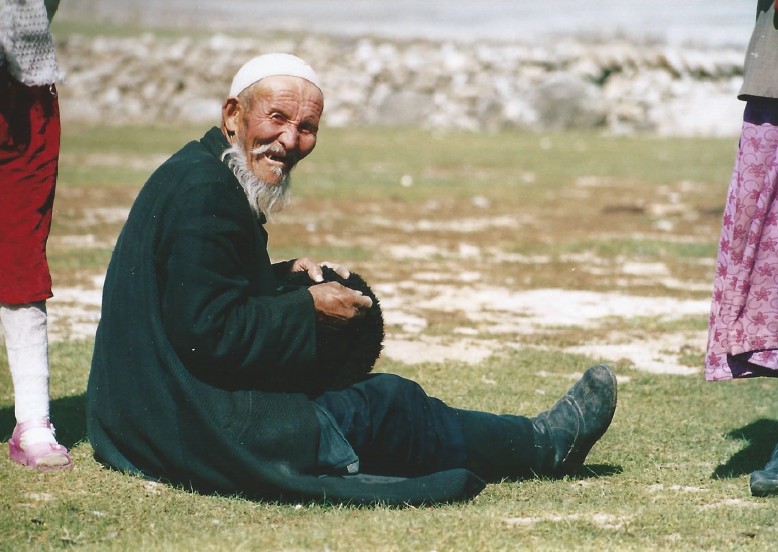

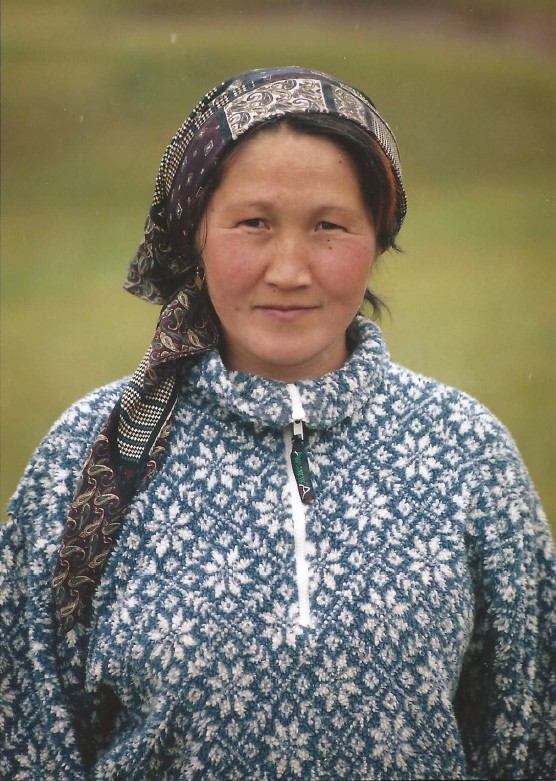

Kyrgyz

The Kyrgyz people (also spelled Kyrghyz and Kirghiz) are a Turkic ethnic group native to Central Asia, primarily Kyrgyzstan.

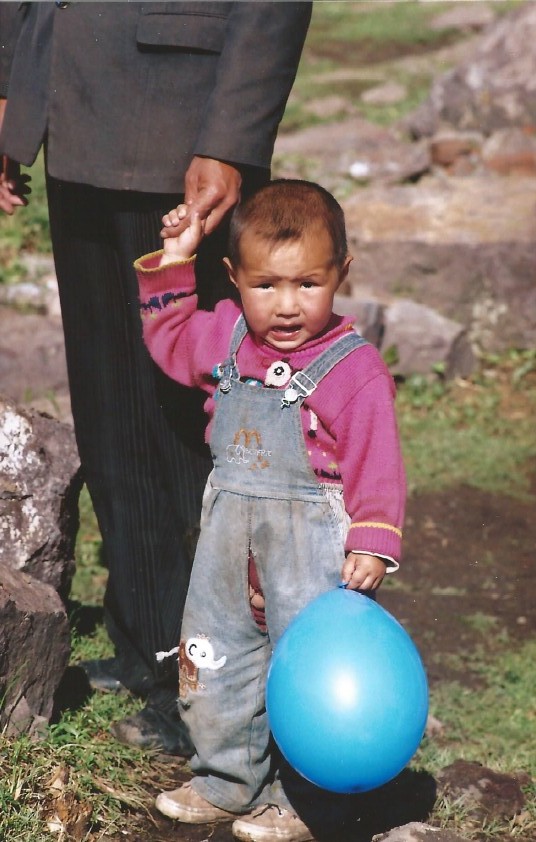

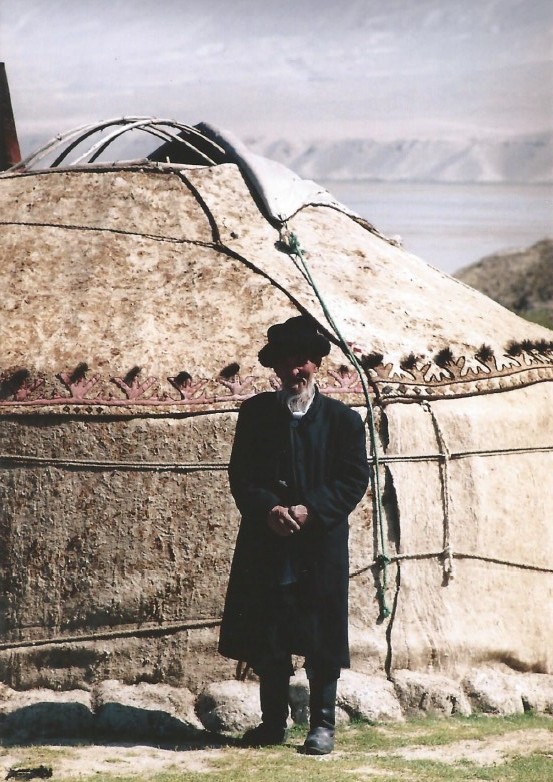

An old kyrgyz man adjusting his traditional sunday hat sitting in the grass in front of a yurt. All dressed up in black because he was attending a funeral. When a Kyrgyz nomad dies he is buried or cremated inside a stone building. This symbolizes him finally arriving at his last but permanent home after a long life as a Nomad, continuously following his lifestock… (Pamir mountains, China 2004)

Kyrgyz nomads do not own a house of stone. They wouldn’t be able to use it very often because they need to follow their horses towards new green pastures. That’s why they live in yurts, which they can transport on horses. But they have a great ritual for their death. They say that after someone dies he finds his final resting place and to honor that person they build a house of stone where he can spend eternity… ?

(Pamir mountains, China 2004)

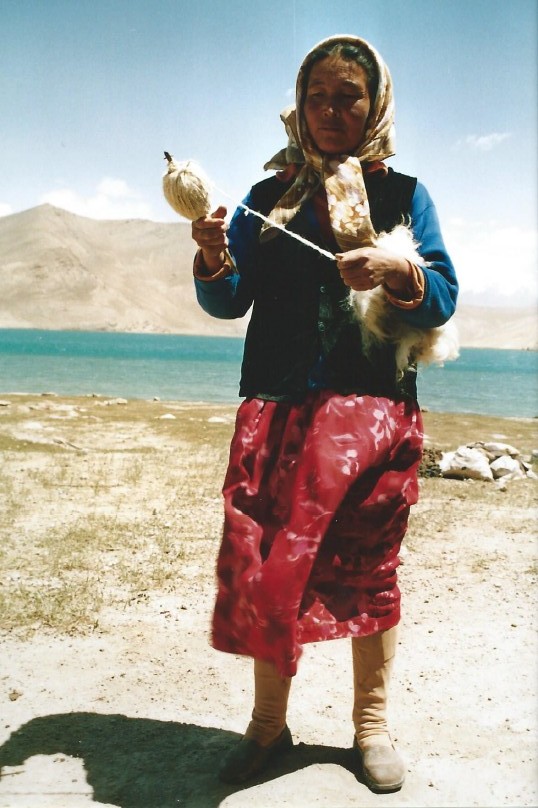

A Kyrgyz nomad lady was showing me how she pulled fiber from a dot of wool… (Pamir mountains, China 2004)

A view from the fireplace within a yurt into the wild world of the Pamir mountains…???

.

(Pamir mountains, China 2004)

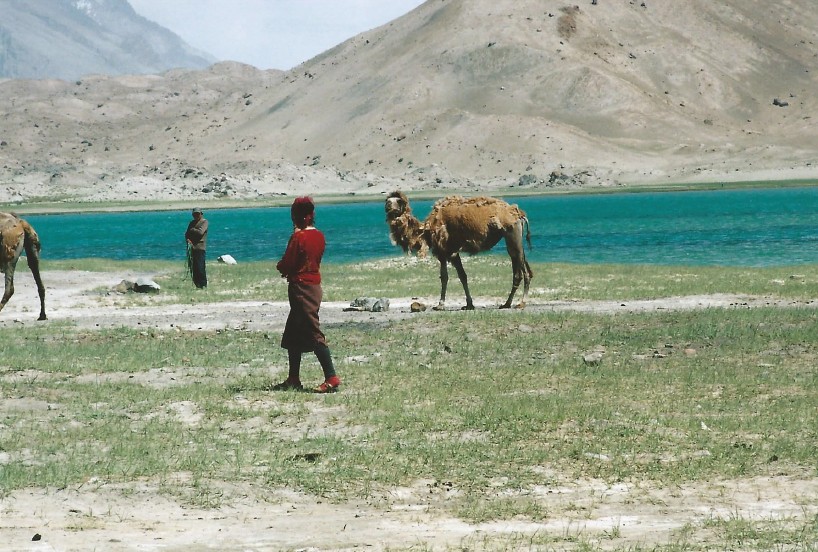

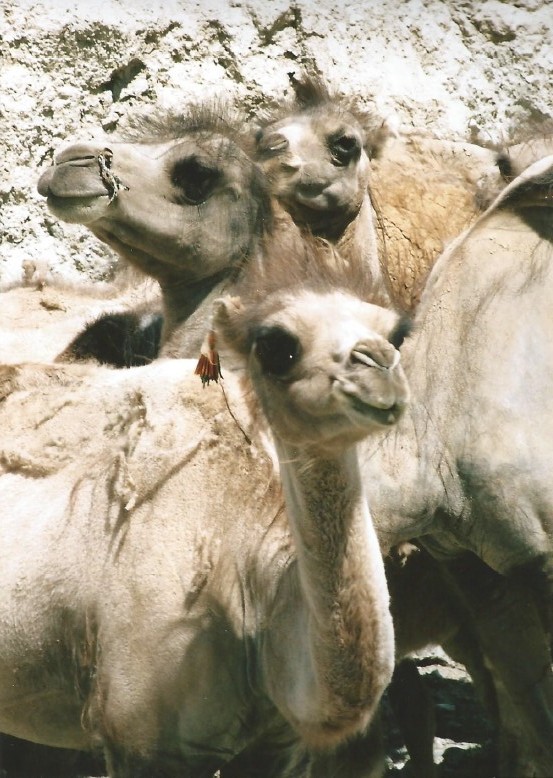

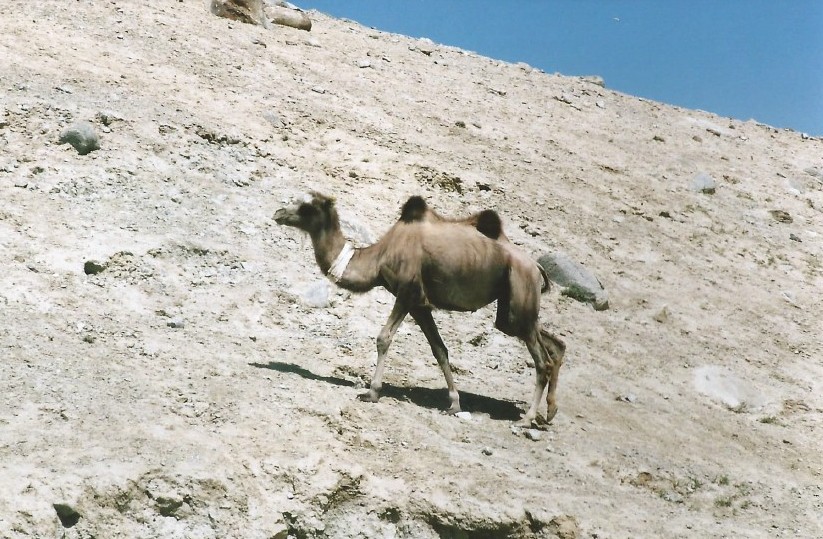

The trick to catching some escaped Bactrian Camels is catching a young one. The others will flock around it and follow wherever it goes… ? .

(Pamir mountains, China 2004)

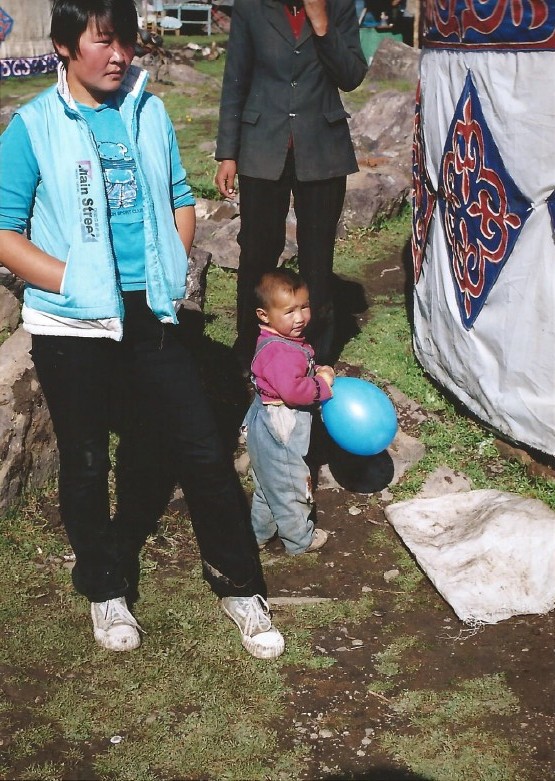

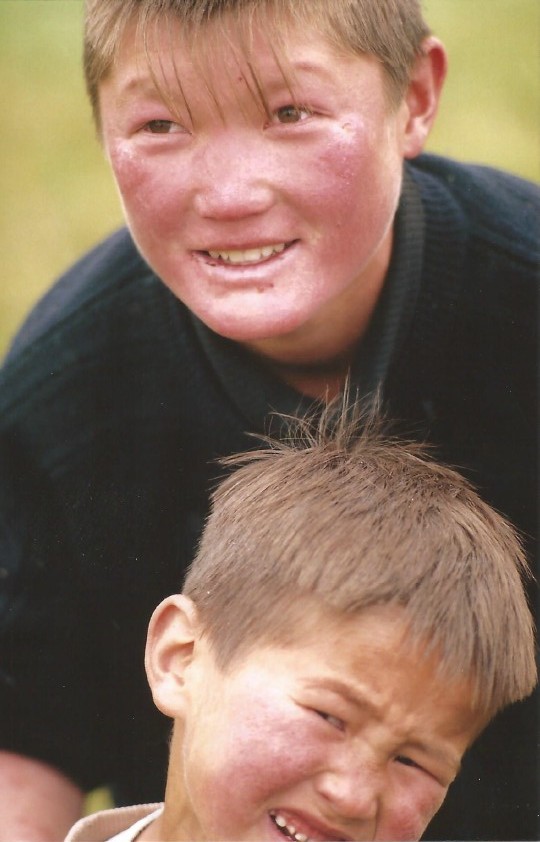

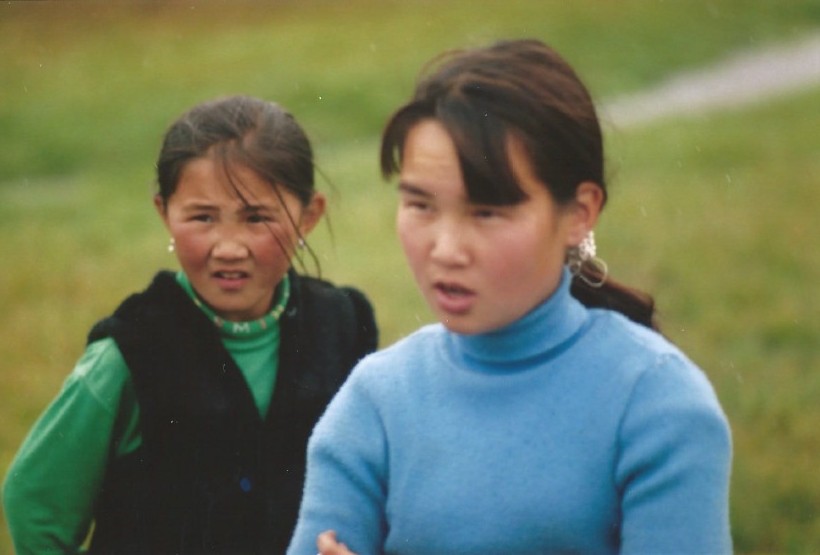

Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyz

The Kyrgyz people (also spelled Kyrghyz and Kirghiz) are a Turkic ethnic group native to Central Asia, primarily Kyrgyzstan.

Hospitality of local kyrgyz nomads showed by invites for a cup of tea or kumiz or simply by giving en route information or weather updates…

South west Namibia

Himba

The Himba are indigenous peoples with an estimated population of about 50,000 people living in northern Namibia, in the Kunene Region (formerly Kaokoland) and on the other side of the Kunene River in Angola. There are also a few groups left of the OvaTwa, who are also OvaHimba, but are hunter-gatherers, but OvaHimba do not like to be associated with OvaTwa. The OvaHimba are a semi-nomadic, pastoralist people, culturally distinguishable from the Herero people in northern Namibia and southern Angola, and speak OtjiHimba, a variety of Herero, which belongs to the Bantu family within Niger–Congo.

The OvaHimba are considered the last (semi-) nomadic people of Namibia.

The Himba tribe in northern Namibia are still living quite traditional due to their isolated homes in Kaokoland…

The Himba tribe members colour their skin with red ocre as a protection against the unforgiving sun…

(Portrait of a Himba woman, Namibia 2015)

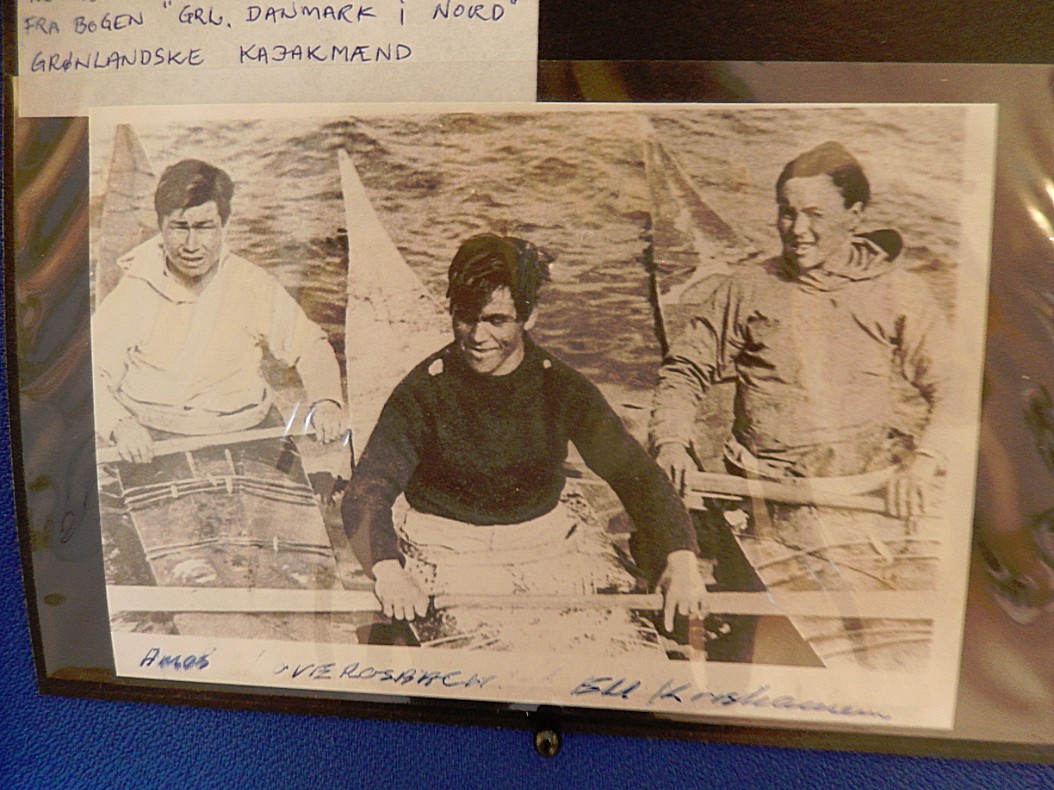

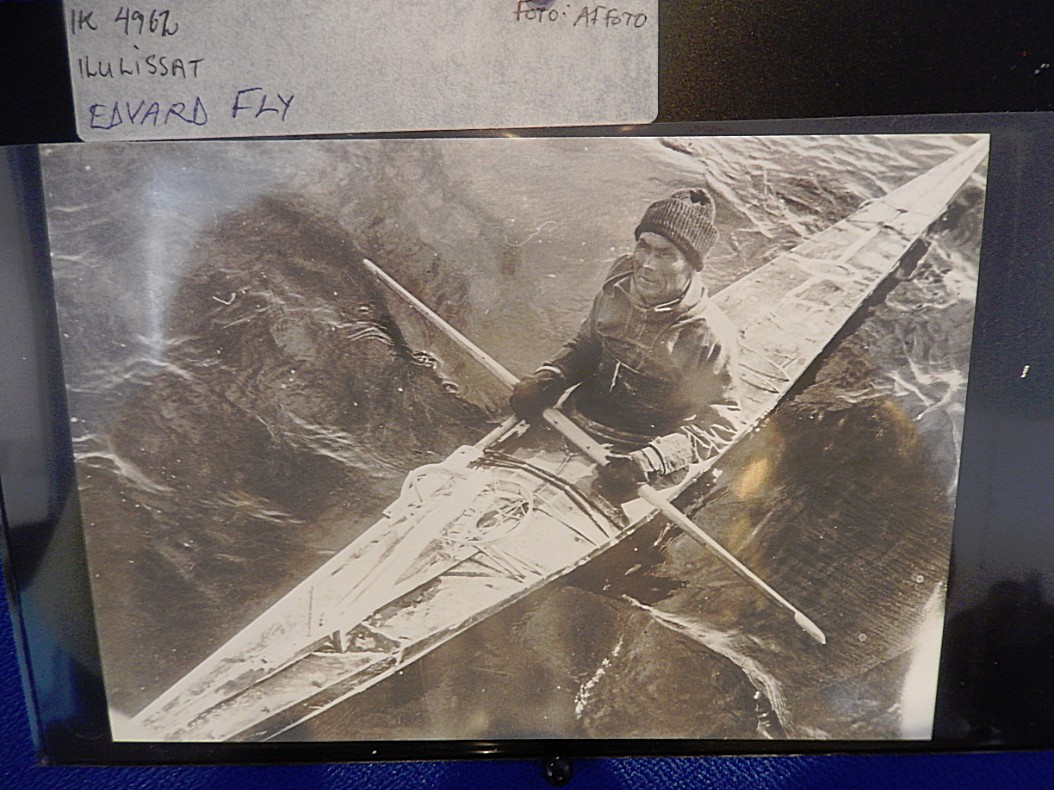

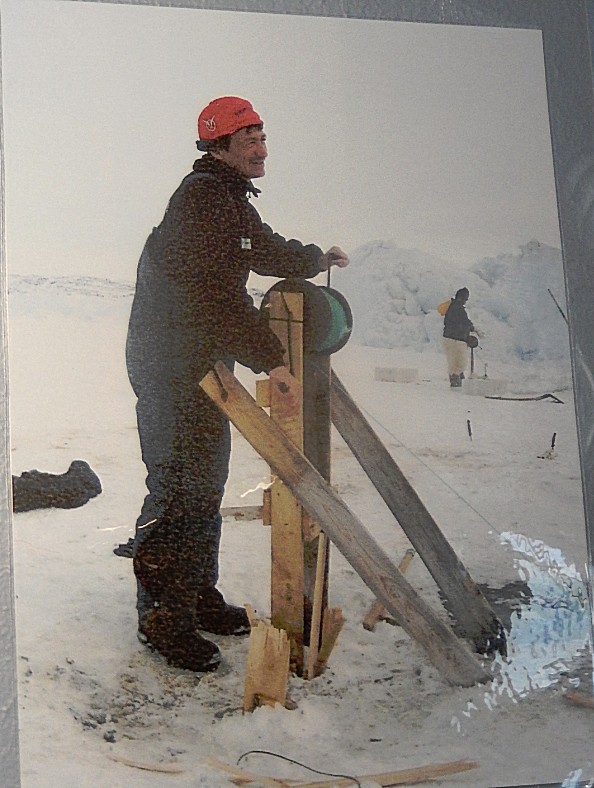

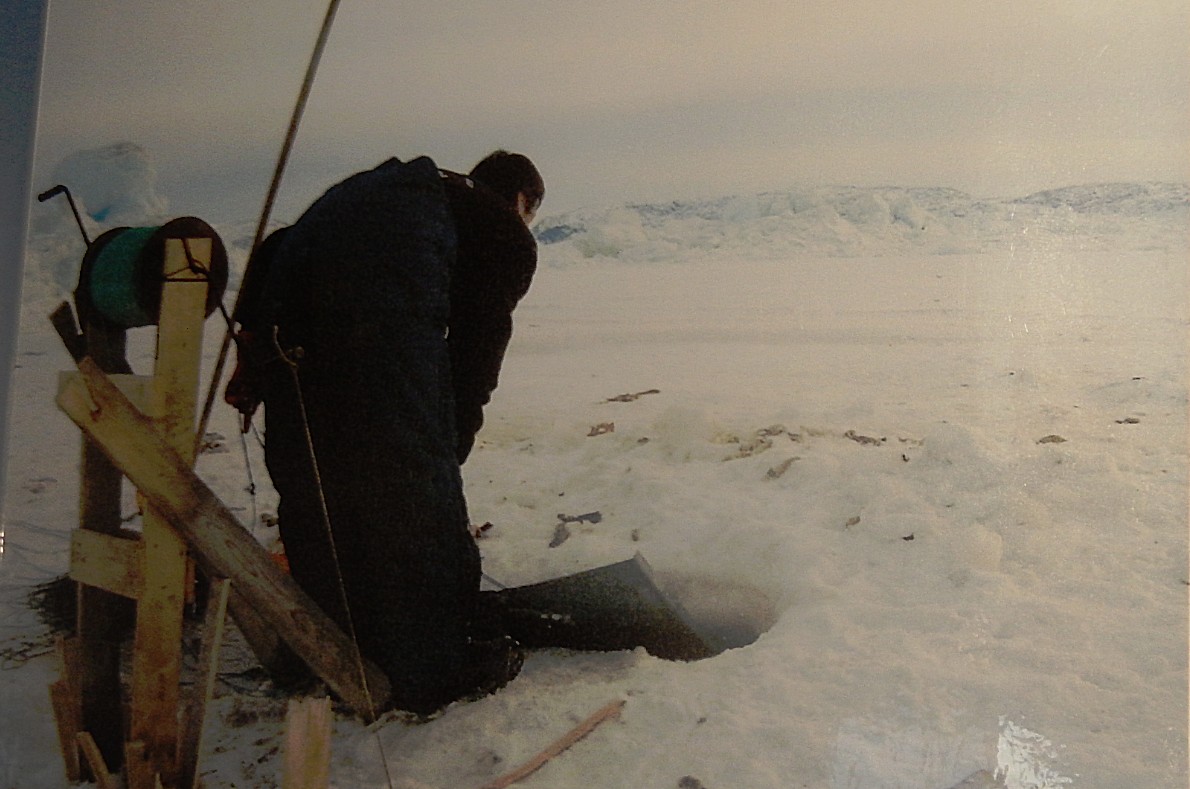

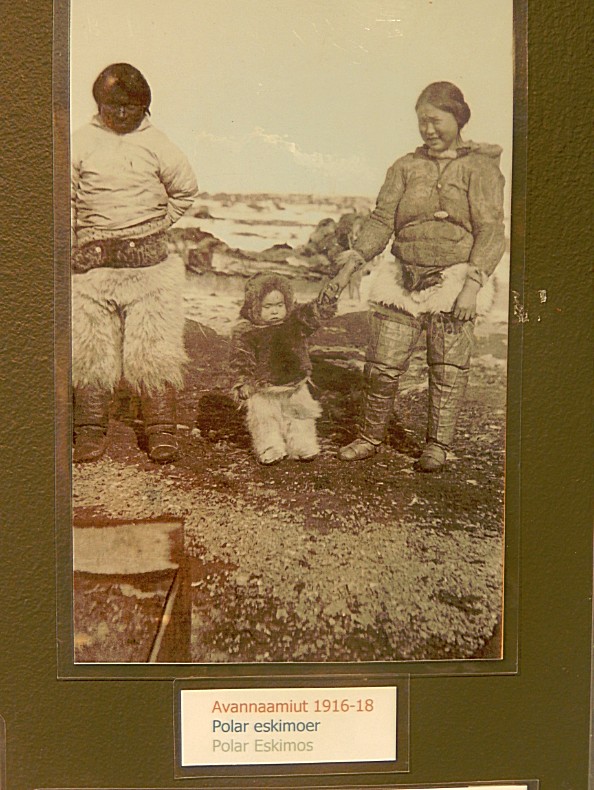

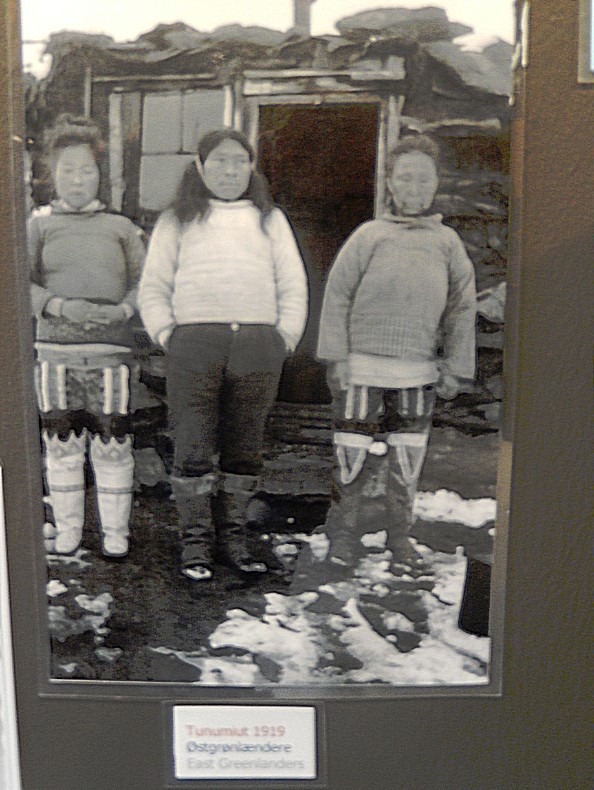

Greenland

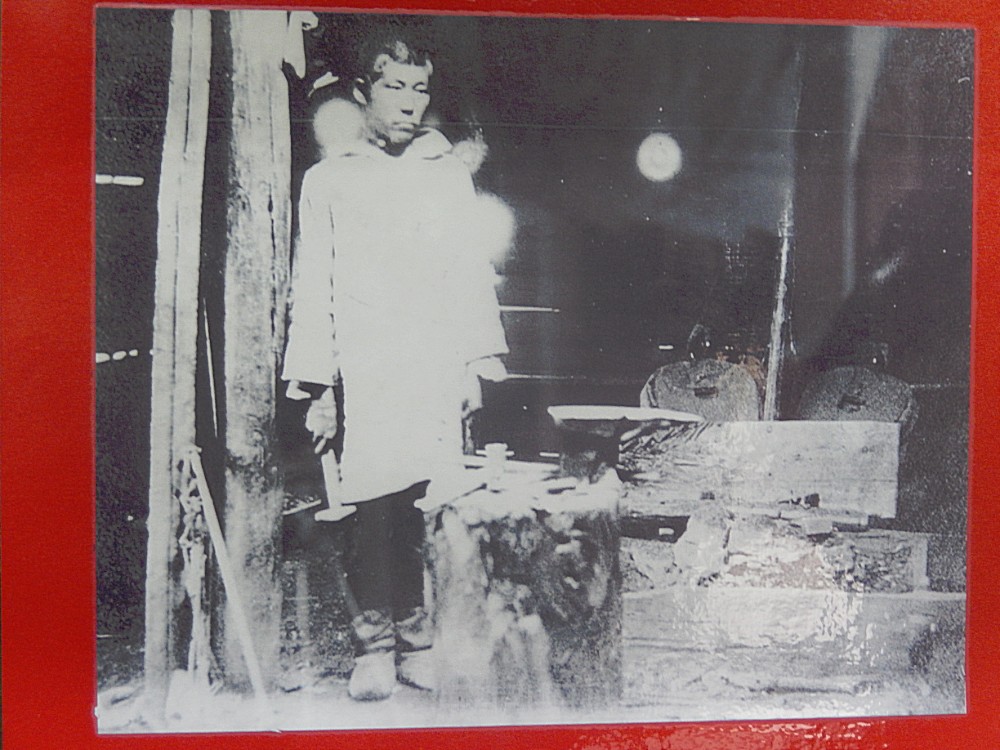

Inuit

The Inuit are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic regions of Greenland, Canada and Alaska. The Inuit languages are part of the Eskimo–Aleut family. Inuit Sign Language is a critically endangered language isolate used in Nunavut.

In Canada and the United States, the term “Eskimo” was commonly used to describe the Inuit and Siberia’s and Alaska’s Yupik and Iñupiat peoples. However, “Inuit” is not accepted as a term for the Yupik, and “Eskimo” is the only term that applies to Yupik, Iñupiat and Inuit. Since the late 20th century, Indigenous peoples in Canada and Greenlandic Inuit consider “Eskimo” to be a pejorative term, and they more frequently identify as “Inuit” for an autonym. In Canada, sections 25 and 35 of the Constitution Act of 1982 classified the Inuit as a distinctive group of Aboriginal Canadians who are not included under either the First Nations or the Métis.

The Inuit live throughout most of Northern Canada in the territory of Nunavut, Nunavik in the northern third of Quebec, Nunatsiavut and NunatuKavut in Labrador, and in various parts of the Northwest Territories, particularly around the Arctic Ocean, in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region. With the exception of NunatuKavut these areas are known in the Inuit languages as Inuit Nunangat.

In the United States, the Iñupiat live primarily on the Alaska North Slope and on Little Diomede Island. The Greenlandic Inuit are descendants of ancient indigenous migrations from Canada, as these people migrated to the east through the continent. They are citizens of Denmark, although not of the European Union.

Sled dogs are the closest cousins to Wolves. That’s why they should never be considered as pets. They are wild animals that are mildly domesticated. In Greenland you’re allowed to keep a dog in town until it is 6 weeks old. Then it has to be transfered to a dog area outside town. Dogs that are kept in town or escape and stroll into town are shot by the police without warning the owner first. This seems cruel but there have been to many violent incidents between dogs and humans in the past. Tourists are not allowed to feed or stroke the adult dogs. (Pic: Adult sled dog, Greenland 2017)

Mongolia

Mongols

The Mongols are a Mongolic ethnic group native to Mongolia and to China’s Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. They also live as minorities in other regions of China (e.g. Xinjiang), as well as in Russia. Mongolian people belonging to the Buryat and Kalmyk subgroups live predominantly in the Russian federal subjects of Buryatia and Kalmykia.

The Mongols are bound together by a common heritage and ethnic identity. Their indigenous dialects are collectively known as the Mongolian language. The ancestors of the modern-day Mongols are referred to as Proto-Mongols.

In 2019, The Wandelgek went on a roadtrip through Mongolia as part of a larger journey with the Trans Siberia and Trans Mongolia Expresses from Moscow towards Beijing. During that roadtrip he spent the night in several Ger camps. A Ger (better known by its Russian name: yurt) is a tent which Mongolian nomads carry with them while trekking behind their herds of sheep, goats, horses, camels or yaks. There are no wild yaks in Mongolia, only domesticated yaks which are a hybrid species between the yak and probably a cattle, but analyses to determine the evolutionary history of yaks have been inconclusive.

Wild yaks are found primarily in northern

Tibet and western Qinghai, with some populations extending into the southernmost parts of Xinjiang, and into Ladakh in India. Small, isolated populations of wild yak are also found farther afield, primarily in western Tibet and eastern Qinghai. In historic times, wild yaks were also found in Nepal and Bhutan, but they are now considered extinct in both countries.

The domestic yak is a long-haired domesticated bovid found throughout the Himalayan region of the Indian subcontinent, the Tibetan Plateau and as far north as Mongolia and Siberia. It is descended from the wild yak. It is also much smaller than the wild yak.

Kumis (also spelled kumiss or koumiss or kumys, see other transliterations and cognate words below under terminology and etymology – Kazakh: қымыз, qymyz) is a fermented dairy product traditionally made from mare’s milk. The drink remains important to the peoples of the Central Asian steppes, of Huno-Bulgar, Turkic and Mongol origin: Kazakhs, Bashkirs, Kalmyks, Kyrgyz, Mongols, and Yakuts.

The Wandelgek had a 1st taste of kumis in Kyrgyzstan. It was on a market in the town of Naryn and it was “young” kumis which tastes like buttermilk. In Mongolia he tried the older fermented kumis and found it tasted quite delicious. It’s milk with a bite (fermentation creates a bit of alcohol and CO2).

Hunting with eagles is a traditional form of falconry found throughout the Eurasian Steppe, practiced by the Kazakhs and the Kyrgyz in contemporary Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, as well as diasporas in Bayan-Ölgii Province, Mongolia (the north west), and Xinjiang, China. Though these people are most famous for hunting with golden eagles, they have been known to train northern goshawks, peregrine falcons, saker falcons, and more.

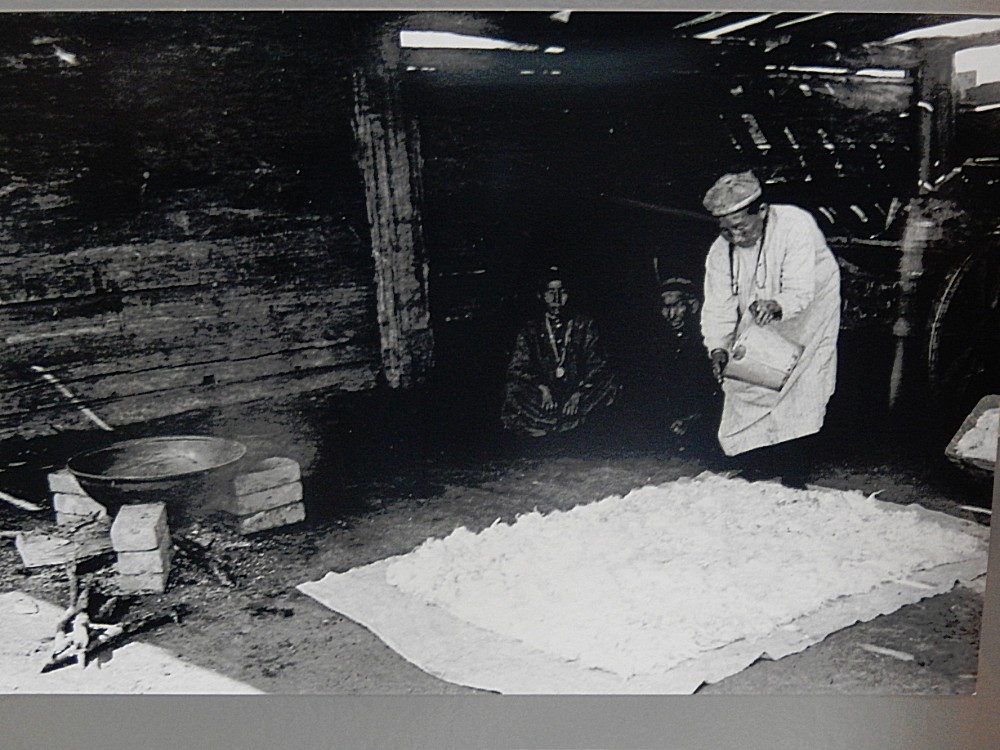

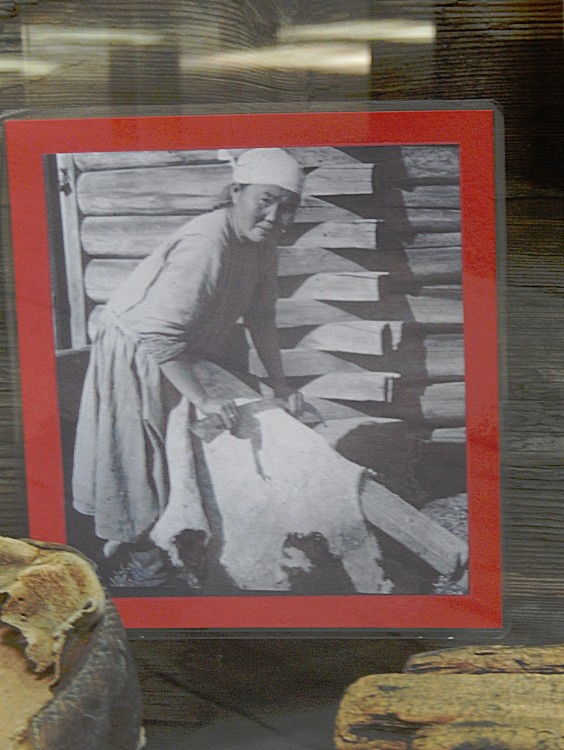

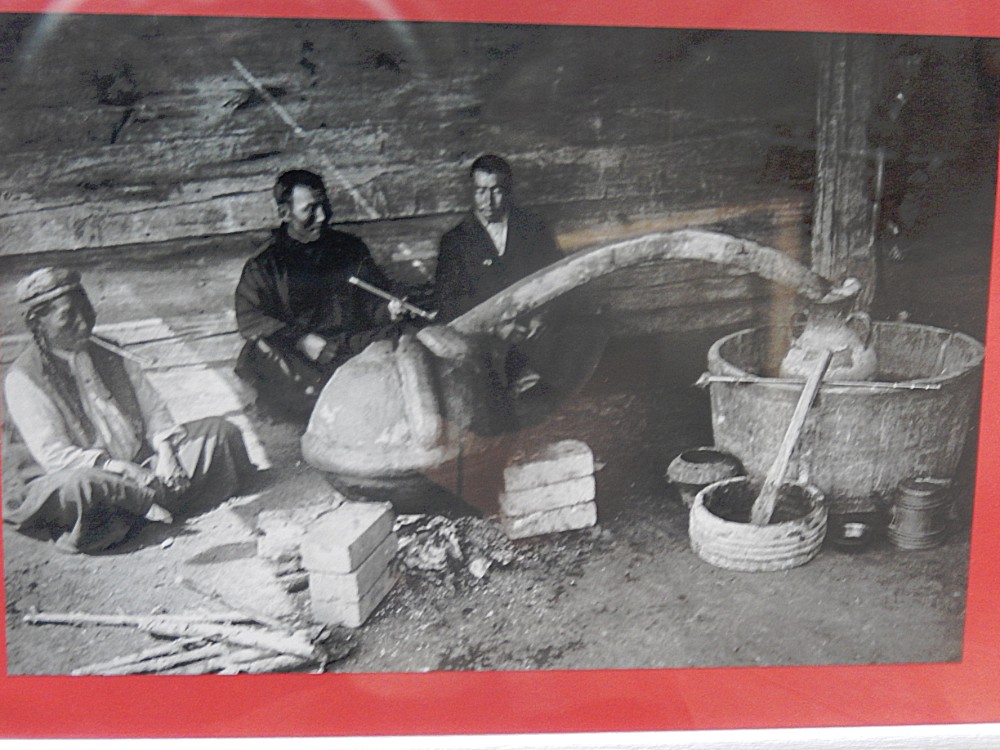

Russia (Siberia)

Buryats

The Buryats are a Mongolic people, numbering approximately 500,000, are the largest indigenous group in Siberia, mainly concentrated in their homeland, the Buryat Republic, a federal subject of Russia. However, some Buryats also live in Mongolia (in the northeast) and in Inner Mongolia in China. They are the major northern subgroup of the Mongols.

Buryats share many customs with other Mongols, including nomadic herding, and erecting gers for shelter. Today, the majority of Buryats live in and around Ulan-Ude, the capital of the Russian republic Buryatia (in Siberia), although many live more traditionally in the countryside. They speak a central Mongolic language called Buryat. According to UNESCO’s 2010 edition of the Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, the Buryat language is classified as severely endangered.

Traditionally, the Buryat were nomadic peoples who kept camels, sheep, goats, cattle, and horses, which they used as beasts of burden, for traveling upon, and to produce meat and milk for sustenance. They were also known for being hunters, fishermen, and gatherers. Their social structure consists of a noble class and a commoner class, and, in earlier times, they also held slaves.

They followed the Buddhist belief system, while some engaged in shamanic practices

The Wild East

In later blogs I will write more about this but I kept noticing some remarkable comparisons between the Siberia, its colonization and the Buryat people (its original inhabitants) and Americas colonization of the Wild West and its original inhabitants, the Indian tribes.

Nomads… are they a disappearing way of life or is the tide turning and are more people like e.g. Digital Nomads embracing this way of life now that the climate is threatened by us polluting our planet in an almost unrestrained way?