33. Greenland: Exploration, settlers, hunters, fishermen and inhabitation, colonialism and maps

In Ilulissat are 2 museums, one for art (Ilulissat Art Museum: see my Ilulissat city walk blog) and one about it’s history simply called the Ilulissat Museum (or Knud Rasmussen’s Museum).

I decided I wanted to learn more about greenland and thus I went to the Knud Rasmussen’s Museum.

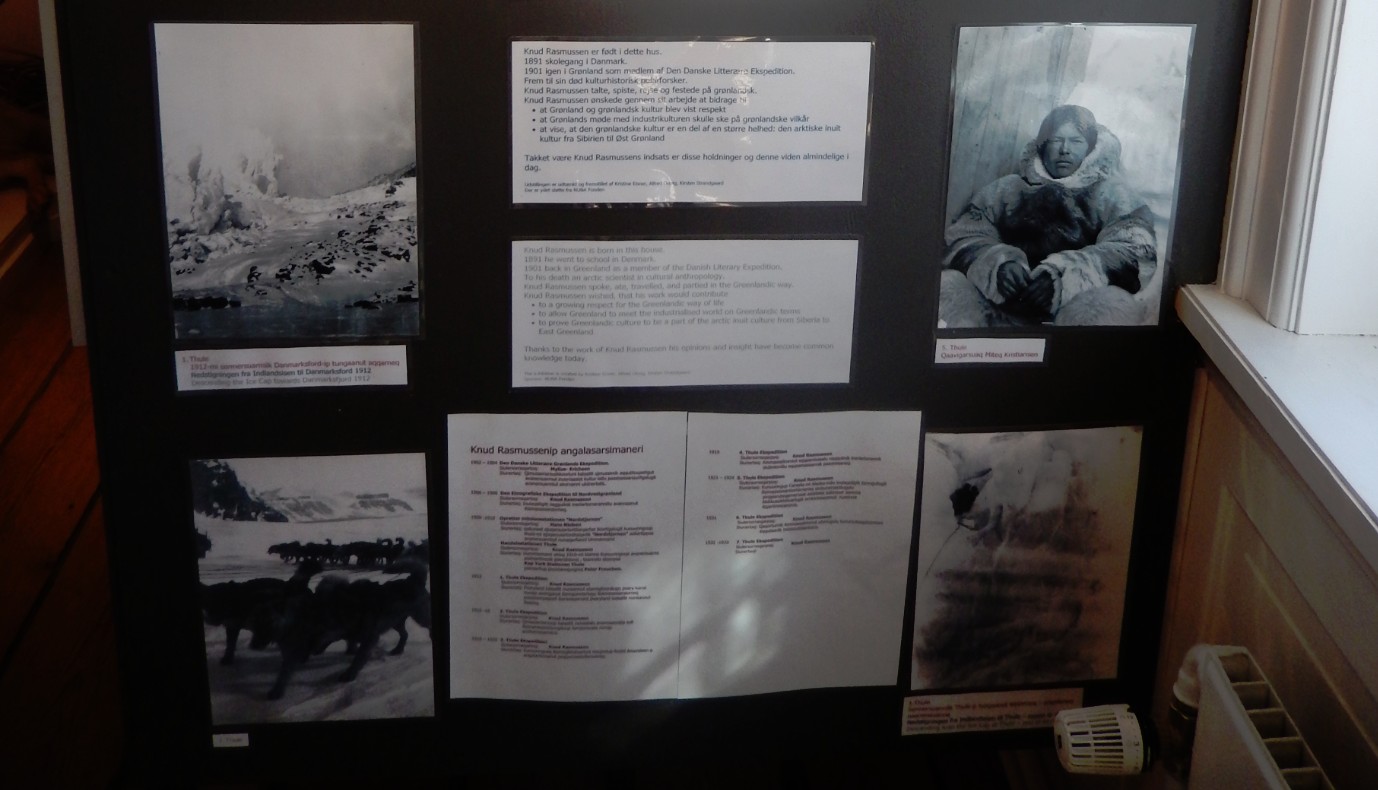

Knud Johan Victor Rasmussen (7 June 1879 – 21 December 1933) was a Greenlandic–Danish polar explorer and anthropologist. He has been called the “father of Eskimology” and was the first European to cross the Northwest Passage via dog sled. He remains well known in Greenland, Denmark and among Canadian Inuit.

Knud Johan Victor Rasmussen (7 June 1879 – 21 December 1933) was a Greenlandic–Danish polar explorer and anthropologist. He has been called the “father of Eskimology” and was the first European to cross the Northwest Passage via dog sled. He remains well known in Greenland, Denmark and among Canadian Inuit.

Above the entrance door was a plaque commemorating this had been his house. It was put there on his 100th birthday (46 years after his death by food poisoning in 1933).

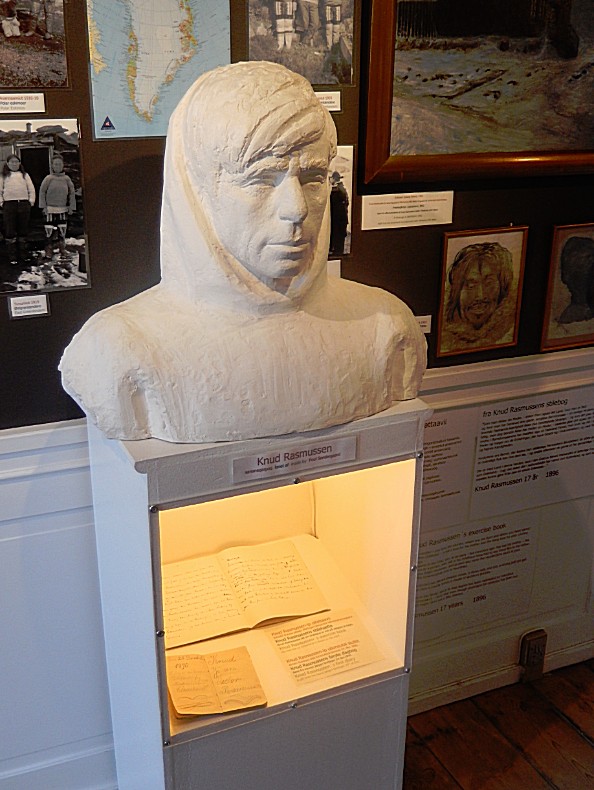

Knud Rasmussen

The museum was located in the Rasmussen family house.

Part of the exhibition inside was dedicated to his life as an accomplished Arctic explorer:

Part of the exhibition inside was dedicated to his life as an accomplished Arctic explorer:

Early years

Rasmussen was born in Jakobshavn, Greenland, the son of a Danish missionary, the vicar Christian Rasmussen, and an Inuit–Danish mother, Lovise Rasmussen (née Fleischer). He had two siblings.

Rasmussen spent his early years in Greenland among the Kalaallit where he learned to speak Kalaallisut, hunt, drive dog sleds and live in harsh Arctic conditions. “My playmates were native Greenlanders; from the earliest boyhood I played and worked with the hunters, so even the hardships of the most strenuous sledge-trips became pleasant routine for me.”

He was later educated in Lynge, North Zealand, Denmark. Between 1898 and 1900 he pursued an unsuccessful career as an actor and opera singer.

Career

He went on his first expedition in 1902–1904, known as The Danish Literary Expedition, with Jørgen Brønlund, Harald Moltke and Ludvig Mylius-Erichsen, to examine Inuit culture. After returning home he went on a lecture circuit and wrote The People of the Polar North (1908), a combination travel journal and scholarly account of Inuit folklore. In 1908, he married Dagmar Andersen.

In 1910, Rasmussen and friend Peter Freuchen established the Thule Trading Station at Cape York (Qaanaaq), Greenland, as a trading base. The name Thule was chosen because it was the most northerly trading post in the world, literally the “Ultima Thule”. Thule Trading Station became the home base for a series of seven expeditions, known as the Thule Expeditions, between 1912 and 1933.

In 1910, Rasmussen and friend Peter Freuchen established the Thule Trading Station at Cape York (Qaanaaq), Greenland, as a trading base. The name Thule was chosen because it was the most northerly trading post in the world, literally the “Ultima Thule”. Thule Trading Station became the home base for a series of seven expeditions, known as the Thule Expeditions, between 1912 and 1933.

The First Thule Expedition (1912, Rasmussen and Freuchen) aimed to test Robert Peary’s claim that a channel divided Peary Land from Greenland. They proved this was not the case in a remarkable 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) journey across the inland ice that almost killed them. Clements Markham, president of the Royal Geographical Society, called the journey the “finest ever performed by dogs.” Freuchen wrote personal accounts of this journey (and others) in Vagrant Viking (1953) and I Sailed with Rasmussen (1958).

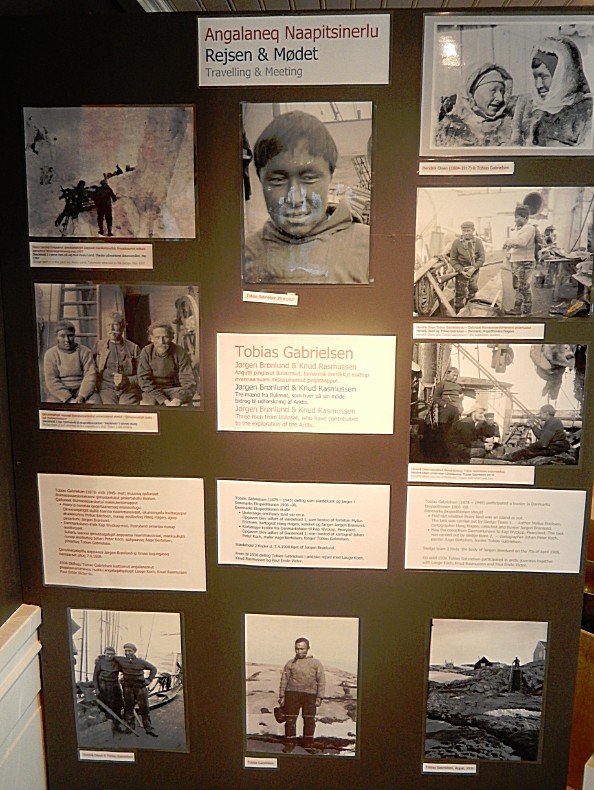

Travelling and meeting

The Second Thule Expedition (1916–1918) was larger with a team of seven men, which set out to map a little-known area of Greenland’s north coast. This journey was documented in Rasmussen’s account Greenland by the Polar Sea (1921). The trip was beset with two fatalities, the only in Rasmussen’s career, namely Thorild Wulff and Hendrik Olsen. The Third Thule Expedition (1919) was depot-laying for Roald Amundsen’s polar drift in Maud. The Fourth Thule Expedition (1919–1920) was in east Greenland where Rasmussen spent several months collecting ethnographic data near Angmagssalik.

The Second Thule Expedition (1916–1918) was larger with a team of seven men, which set out to map a little-known area of Greenland’s north coast. This journey was documented in Rasmussen’s account Greenland by the Polar Sea (1921). The trip was beset with two fatalities, the only in Rasmussen’s career, namely Thorild Wulff and Hendrik Olsen. The Third Thule Expedition (1919) was depot-laying for Roald Amundsen’s polar drift in Maud. The Fourth Thule Expedition (1919–1920) was in east Greenland where Rasmussen spent several months collecting ethnographic data near Angmagssalik.

Rasmussen’s “greatest achievement” was the massive Fifth Thule Expedition (1921–1924) which was designed to “attack the great primary problem of the origin of the Eskimo race.” A ten volume account (The Fifth Thule Expedition 1921–1924 (1946)) of ethnographic, archaeological and biological data was collected, and many artifacts are still on display in museums in Denmark. The team of seven first went to eastern Arctic Canada where they began collecting specimens, taking interviews (including the shaman Aua, who told him of Uvavnuk), and excavating sites.

Rasmussen’s “greatest achievement” was the massive Fifth Thule Expedition (1921–1924) which was designed to “attack the great primary problem of the origin of the Eskimo race.” A ten volume account (The Fifth Thule Expedition 1921–1924 (1946)) of ethnographic, archaeological and biological data was collected, and many artifacts are still on display in museums in Denmark. The team of seven first went to eastern Arctic Canada where they began collecting specimens, taking interviews (including the shaman Aua, who told him of Uvavnuk), and excavating sites.

Rasmussen left the team and traveled for 16 months with two Inuit hunters by dog sled across North America to Nome, Alaska – he tried to continue to Russia but his visa was refused. He was the first European to cross the Northwest Passage via dog sled. His journey is recounted in Across Arctic America (1927), considered today a classic of polar expedition literature. This trip has also been called the “Great Sled Journey” and was dramatized in the Canadian film The Journals of Knud Rasmussen (2006).

For the next seven years Rasmussen traveled between Greenland and Denmark giving lectures and writing. In 1931, he went on the Sixth Thule Expedition, designed to consolidate Denmark’s claim on a portion of eastern Greenland that was contested by Norway.

The Seventh Thule Expedition (1933) was meant to continue the work of the sixth, but Rasmussen contracted pneumonia after an episode of food poisoning attributed to eating kiviaq, dying a few weeks later in Copenhagen at the age of 54.

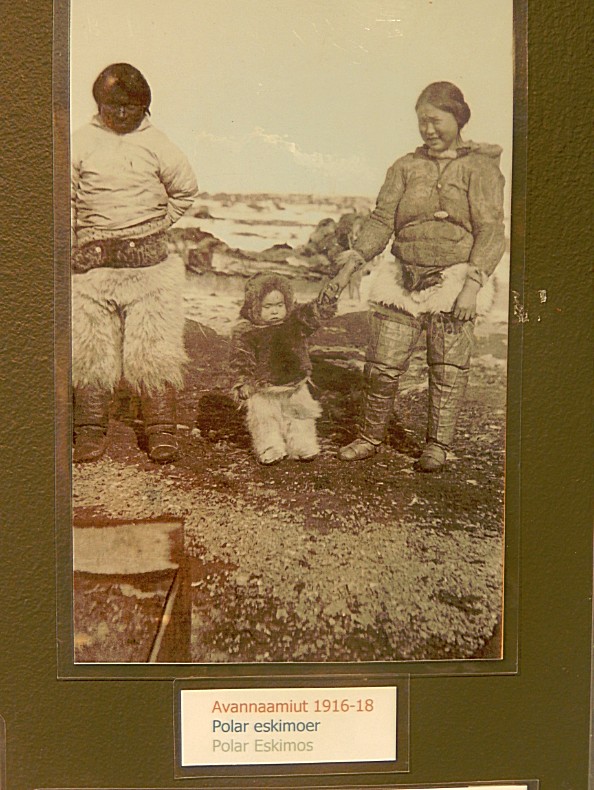

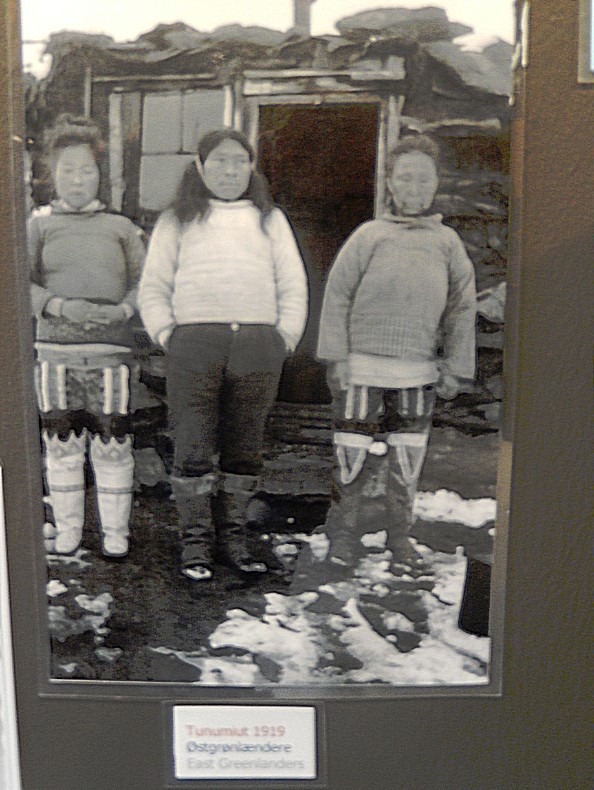

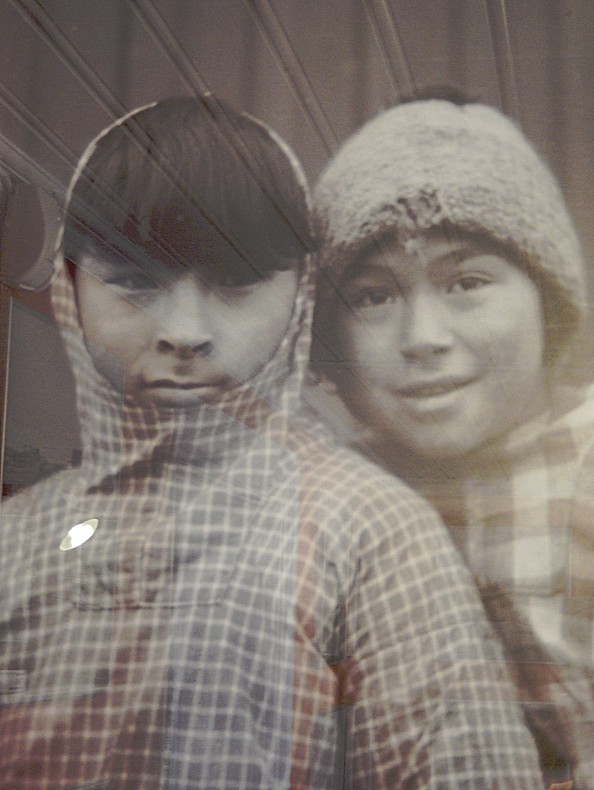

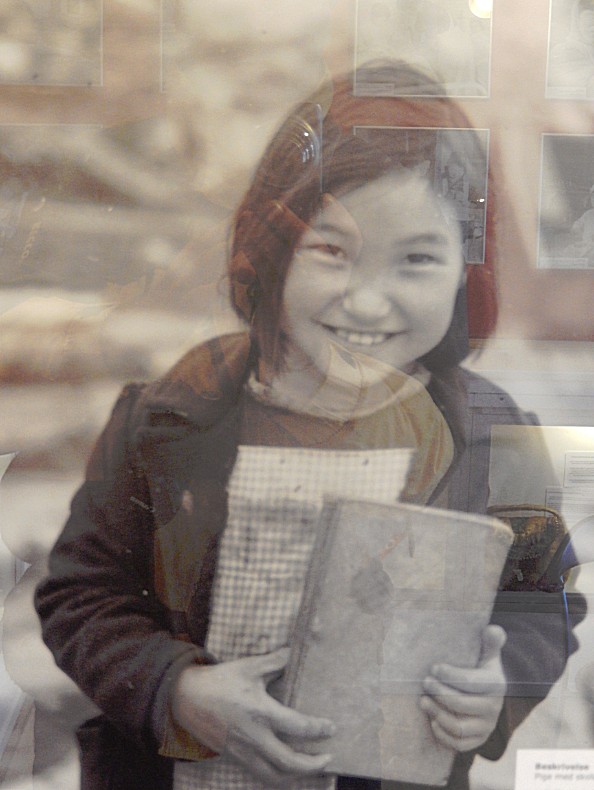

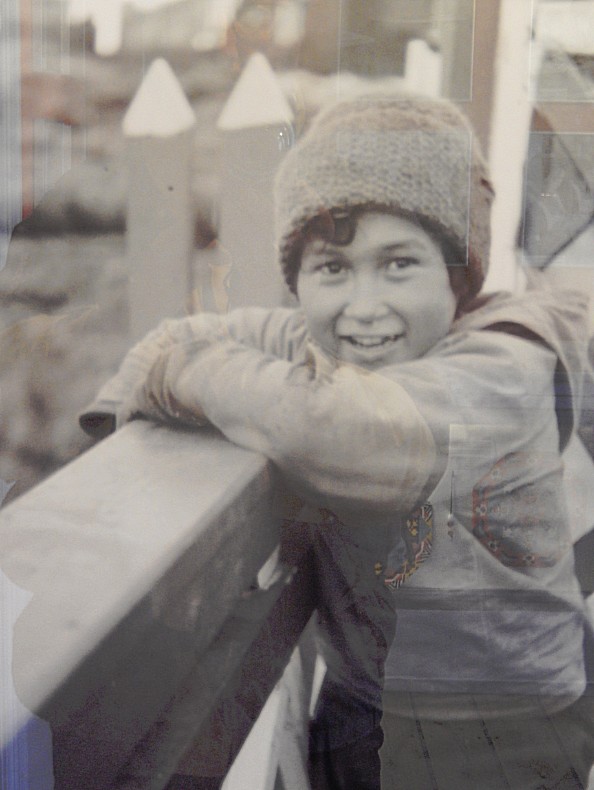

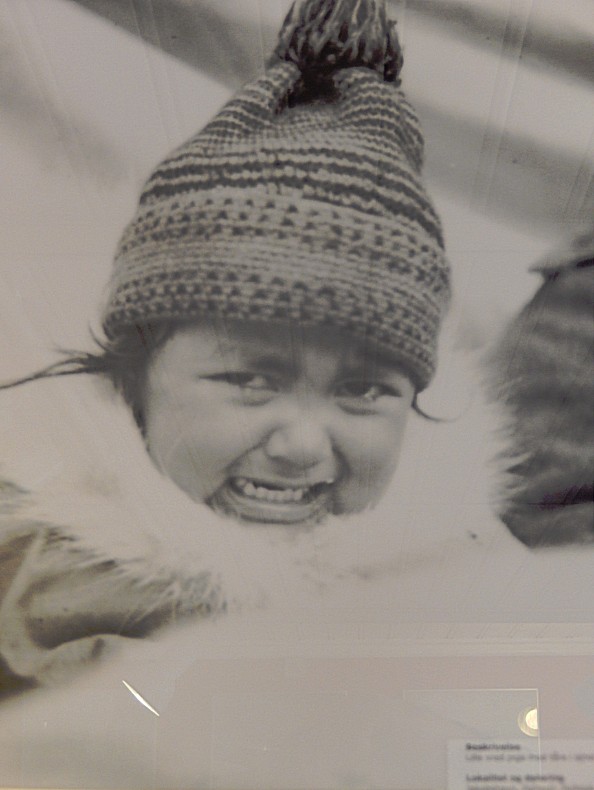

Picture Gallery

I loved the huge amount of pictures of Greenlandic Inuit people. The 2nd and last picture also show a bit of the traditional houses where they lived long ago…

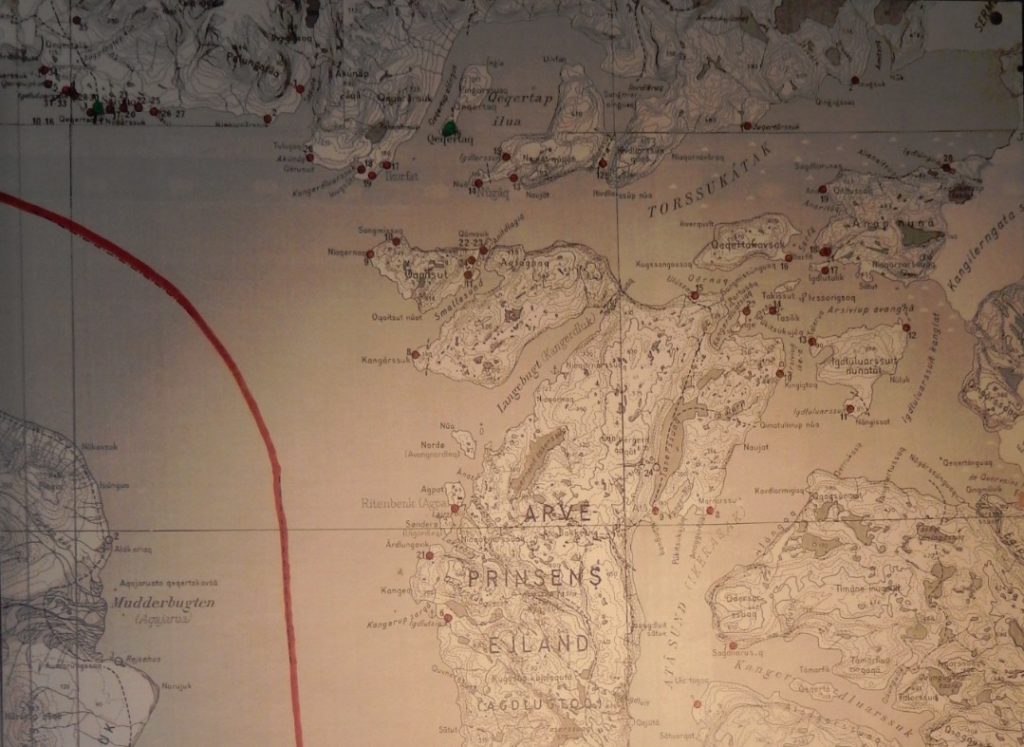

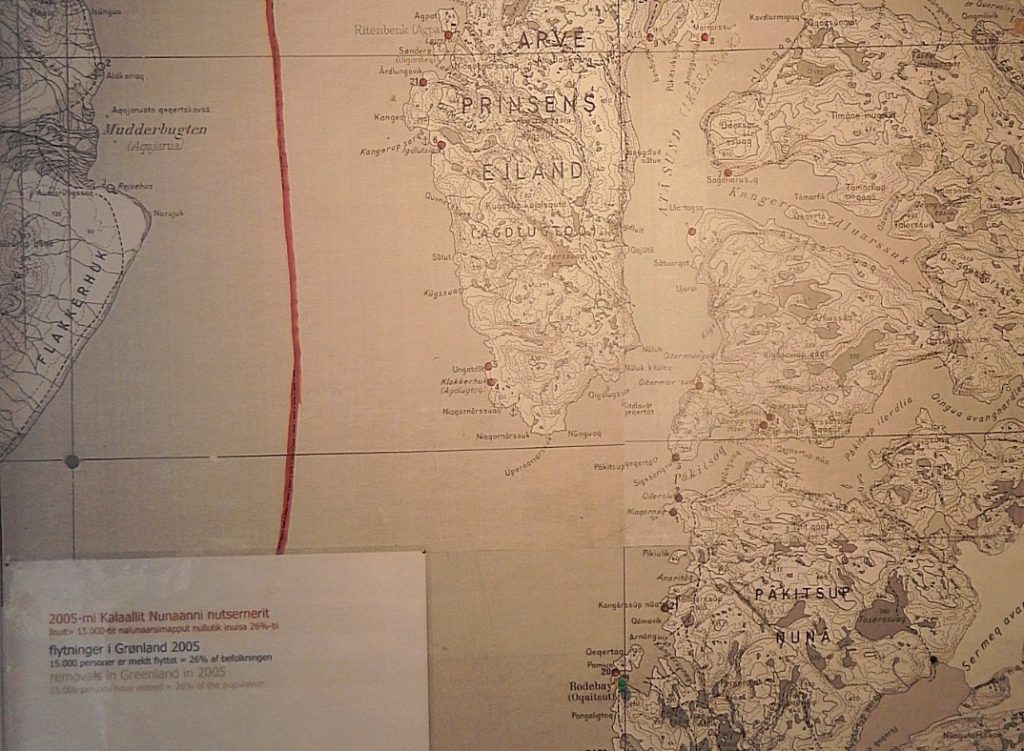

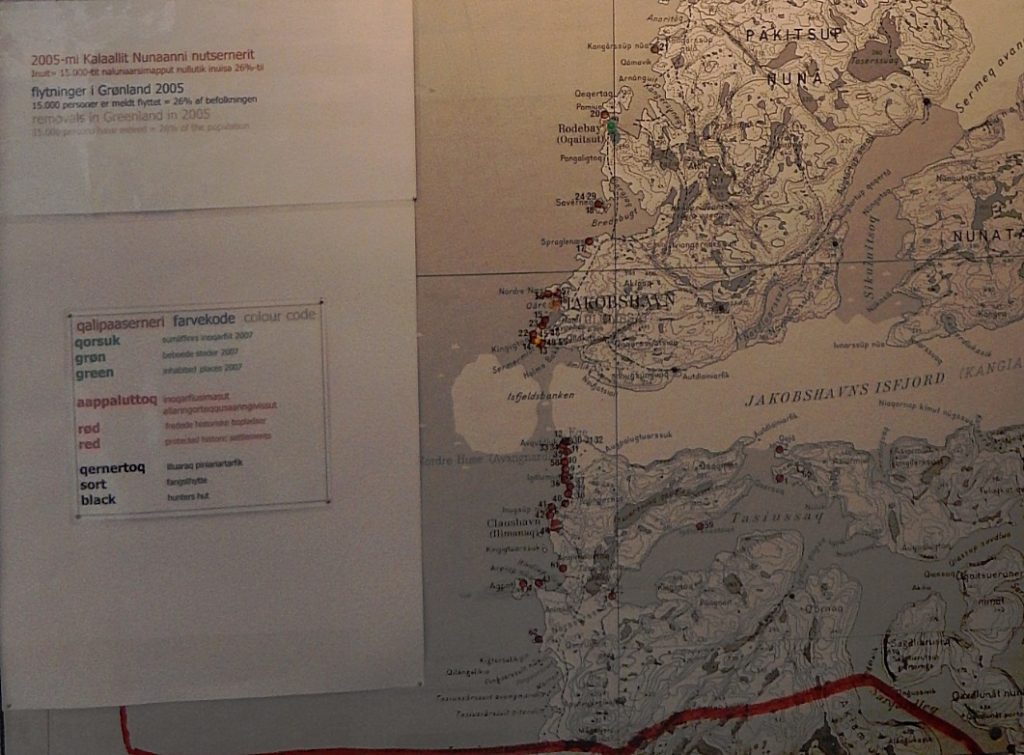

Empty ghost villages

Beneath is a large map showing a problem that Greenland is trying to deal with for some time now. It shows that in 2005, 15,000 people had to move from their homes into other locations. Small villages had seen decline in population and also the profitable but polluting mining of coal was prohibited which caused settlements dependent on mining (like some on Qeqertarssuacs east coast), to become uninhabitable. Forced relocations in 2005 of 15,000 villagers (20% of the countries total population!) were needed, mostly to Ilulissat, supporting urbanization in an effort to modernize the country. Today, many trace Greenland’s soaring rates of suicide and alcohol abuse back to this social upheaval.

Many young Greenlanders are still leaving small villages for more urban centers, both in Greenland and abroad, in search of educational and occupational opportunities that don’t exist in rural areas. Far more women leave than men.

But there are tourist projects like the one in Ilimanaq that might brin this trend to a halt (See my Whale hunt blog for more info on this).

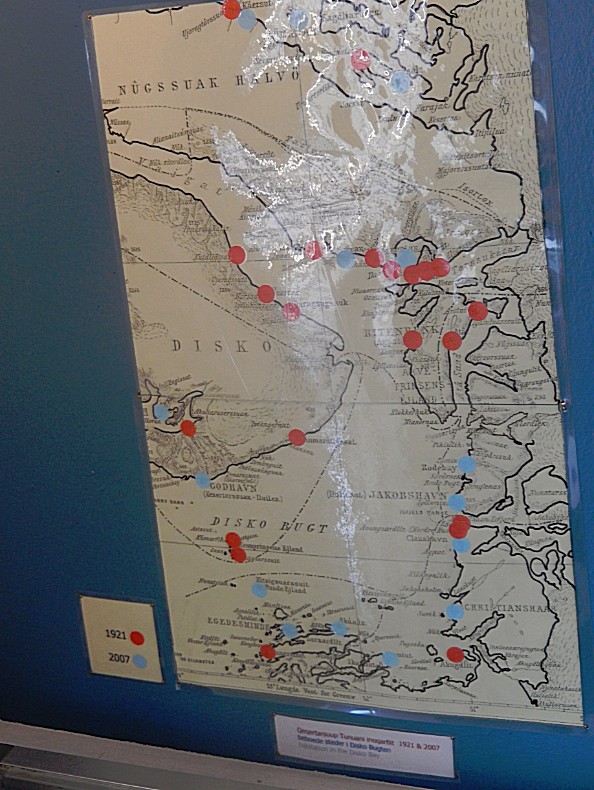

This last map shows the decline in villages between 1921 and 2007 (2 years after the massive 2005 relocations):

Historic inhabitation of Greenland

Historic inhabitation of Greenland

Sermermiut

Sermermiut was an Inuit settlement in the Disko Bay, Greenland. The location is now part of the Ilulissat Icefjord World Heritage Site.

History

The pre-colonial history of Sermermiut was pieced together by a series of archaeological excavations during the twentieth century. The area became an area of archaeological interest at the start of the century, although the results were not well documented. A 1953 dig identified that Sermermiut had been used by Saqqaq, Early Dorset and Thule cultures. Another dig in 1983 dated the start of the Early Dorset settlement at around 600–200 BCE.

Saqqaq

The Saqqaq culture (named after the Saqqaq settlement, the site of many archaeological finds) was a Paleo-Eskimo culture in southern Greenland. Up to this day, no other people seem to have lived in Greenland continually for as long as the Saqqaq.

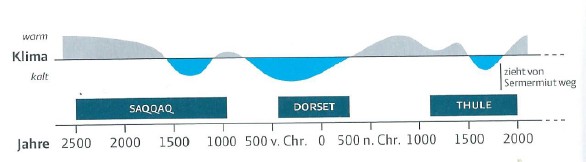

Timeframe

The earliest known archaeological culture in southern Greenland, the Saqqaq existed from around 2500 BCE until about 800 BCE. This culture coexisted with the Independence I culture of northern Greenland, which developed around 2400 BCE and lasted until about 1300 BCE. After the Saqqaq culture disappeared, the Independence II culture of northern Greenland and the Early Dorset culture of West Greenland emerged. There is some debate about the timeframe of the transition from Saqqaq culture to Early Dorset in western Greenland.

The Saqqaq culture came in two phases, the main difference of the two being that the newer phase adapted the use of sandstone. The younger phase of the Saqqaq culture coincides with the oldest phase of the Dorset culture.

Archaeological findings

Frozen remains of a Saqqaq dubbed “Inuk” were found in western Greenland (Qeqertarsuaq) and have been DNA sequenced. He had brown eyes, black hair, and shovel-shaped teeth. It has been determined that he lived about 4000 years ago, and was related to native populations in northeastern Siberia. The Saqqaq people are not the ancestors of contemporary Kalaallit people, but instead are related to modern Chukchi and Koryak peoples. It is not known whether they crossed in boats or over ice.

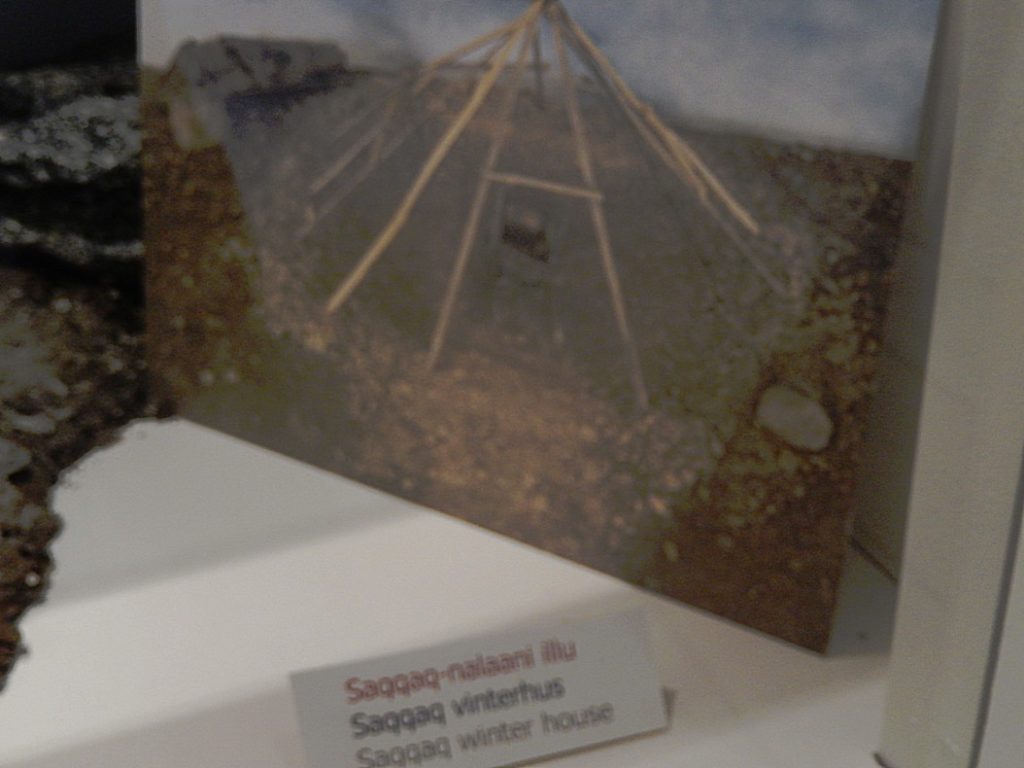

Saqqaq people lived in small tents and hunted seals, seabirds, and other marine animals. The people of the Saqqaq culture used silicified slate, agate, quartzite, and rock crystals as materials for their tools.

Saqqaq Winter house

Early Dorset

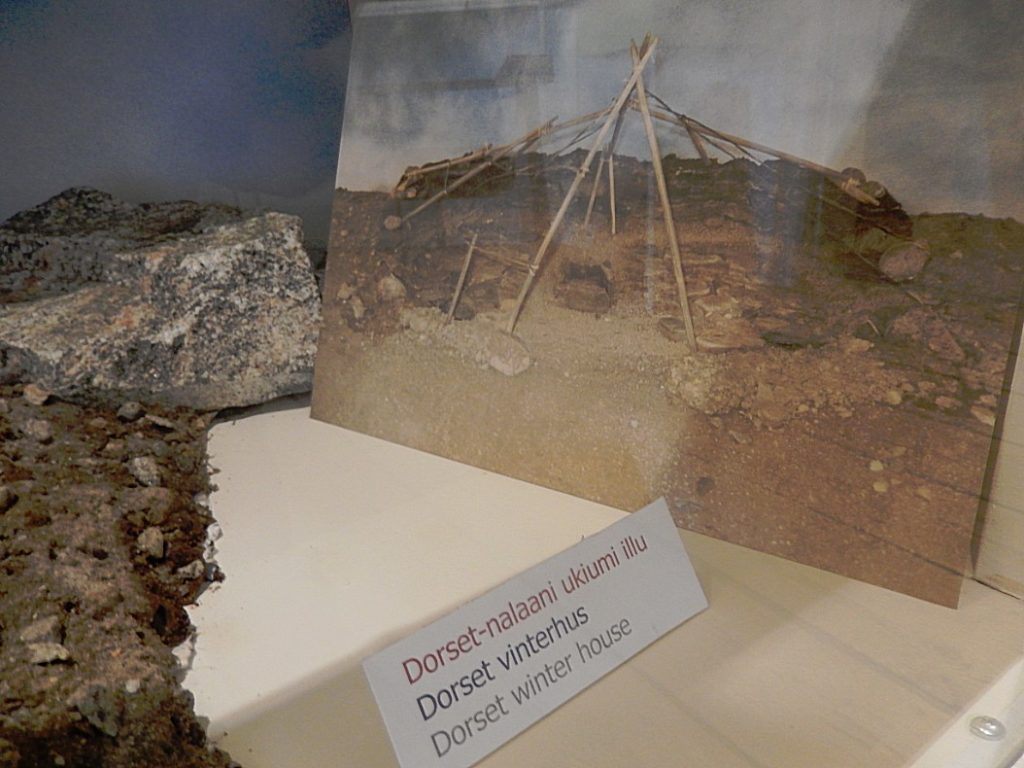

The Dorset was a Paleo-Eskimo culture, lasting from 500 BC to between 1000 and 1500 AD, that followed the Pre-Dorset and preceded the Inuit in the Arctic of North America. It is named after Cape Dorset in Nunavut, Canada where the first evidence of its existence was found. The culture has been defined as having four phases due to the distinct differences in the technologies relating to hunting and tool making. Artifacts include distinctive triangular end-blades, soapstone lamps, and burins.

The Dorset were first identified as a separate culture in 1925. The Dorset appear to have been extinct by 1500 at the latest and perhaps as early as 1000. The Thule people, who began migrating east from Alaska in the 11th century, ended up spreading through the lands previously inhabited by the Dorset. There is no strong evidence that the Inuit and Dorset ever met. Modern genetic studies show the Dorset population were distinct from later groups and that “[t]here was virtually no evidence of genetic or cultural interaction between the Dorset and the Thule peoples.”

Inuit legends recount them encountering people they called the Tuniit (singular Tuniq) or Sivullirmiut “First Inhabitants”. According to legend, the First Inhabitants were giants, taller and stronger than the Inuit but afraid to interact and “easily put to flight.” There is also a theory of contact and trade between the Dorset and the Norse.

Early Dorset Winter house

Finished house

Discovery

In 1925 anthropologist Diamond Jenness received some odd artifacts from Cape Dorset. As they were quite different from those of the Inuit, he speculated that they were indicative of an ancient, preceding culture. Jenness named the culture “Dorset” after the location of the find. These artifacts showed a consistent and distinct cultural pattern that included sophisticated art distinct from that of the Inuit. For example, the carvings featured uniquely large hairstyles for women, and figures of both sexes wearing hoodless parkas with large, tall collars. Much research since then has revealed many details of the Dorset people and their culture.

History

Origins

The origins of the Dorset people are not well understood. They may have developed from the previous cultures of Pre-Dorset, Saqqaq or (less likely) Independence I. There are, however, problems with this theory: these earlier cultures had bow and arrow technology which the Dorsets lacked. Possibly due to a shift from terrestrial to aquatic hunting, the bow and arrow became lost to the Dorset. Another piece of technology that is missing from the Dorset are drills: there are no drill holes in Dorset artifacts. Instead, the Dorset gouged lenticular holes. For example, bone needles are common in Dorset sites, but they have long and narrow holes that have been painstakingly carved or gouged. Both the Pre-Dorset and Thule (Inuit) had drills.

Historical and cultural periods

Dorset culture and history is divided into four periods: the Early (500-1 BC), Middle (AD 1-500), and Late phases (AD 500-1000), as well perhaps as a Terminal phase (from c. AD 1000). The Terminal phase, if it existed, would likely be closely related to the onset of the Medieval Warm Period, which started to warm the Arctic considerably around AD 950. With the warmer climates, the sea ice became less predictable and was isolated from the High Arctic.

The Dorset were highly adapted to living in a very cold climate, and much of their food is thought to have been from hunting sea mammals that breathe through holes in the ice. The massive decline in sea-ice which the Medieval Warm Period produced would have strongly affected the Dorset. They could have followed the ice north. Most of the evidence suggests that they disappeared some time between AD 1000 and 1500. Scientists have suggested that they disappeared because they were unable to adapt to climate change or that they were vulnerable to newly introduced disease.

Technology

The Dorset adaptation was different from that of the whaling-based Thule Inuit. Unlike the Inuit, they rarely hunted land animals, such as polar bears and caribou. They did not use bows or arrows. Instead, they seem to have relied on seals and other sea mammals that they apparently hunted from holes in the ice. Their clothing must have been adapted to the extreme conditions.

Triangular end-blades, soapstone, and burins are diagnostic of the Dorset. The end-blades were hafted onto harpoon heads. They primarily used the harpoons to hunt seal, but also hunted larger sea mammals such as walrus and narwhals. They made kudlik lamps from soapstone and filled them with seal oil. Burins were a type of stone flake with a chisel-like edge. They were probably either used for engraving or for carving wood or bone. The burins were also used by Pre-Dorset groups and had distinctive mitten shape.

The Dorset were highly skilled at making refined miniature carvings, and striking masks. Both indicate an active shamanistic tradition. The Dorset culture was remarkably homogeneous across the Canadian Arctic, but there were some important variations which have been noted in both Greenland and Newfoundland/Labrador regions.

Interaction with the Inuit

There appears to be no genetic connection between the Dorset and the Thule who replaced them. Archaeological and legendary evidence is often thought to support some cultural contact, but this has been questioned. The Thule, for instance, engaged in seal-hole hunting, a method which requires several steps and includes the use of dogs. The Thule apparently did not use this technique in the time they had previously spent in Alaska. Settlement pattern data has been used to claim that the Dorset also extensively used a breathing-hole sealing technique and perhaps they would have taught this to the Inuit. But this has been questioned on the grounds that there is no evidence that the Dorset had dogs.

Some elders describe peace with an ancient group of people, while others describe conflict.

The Sadlermiut

The Sadlermiut were a people living in near isolation mainly on and around Coats Island, Walrus Island, and Southampton Island in Hudson Bay up until 1902–03. Encounters with Europeans and exposure to infectious disease caused the deaths of the last members of the Sadlermiut.

Scholars had believed the Sadlermiut were the last remnants of the Dorset culture, as they had a culture and dialect distinct from the mainland Inuit. Supporting this a 2002 mitochondrial DNA research showed that the Sadlermiut bore a mitochrondrial relationship to both the Dorset and Thule peoples, perhaps suggesting local admixture.

However a subsequent 2012 genetic analysis showed no genetic link between the Sadlermiut and the Dorset.

Thule

The Thule or proto-Inuitwere the ancestors of all modern Inuit. They developed in coastal Alaska by 1000 and expanded eastwards across Canada, reaching Greenland by the 13th century. In the process, they replaced people of the earlier Dorset culture that had previously inhabited the region. The appellation “Thule” originates from the location of Thule (relocated and renamed Qaanaaq in 1953) in northwest Greenland, facing Canada, where the archaeological remains of the people were first found at Comer’s Midden. The links between the Thule and the Inuit are biological, cultural, and linguistic.

The Thule or proto-Inuitwere the ancestors of all modern Inuit. They developed in coastal Alaska by 1000 and expanded eastwards across Canada, reaching Greenland by the 13th century. In the process, they replaced people of the earlier Dorset culture that had previously inhabited the region. The appellation “Thule” originates from the location of Thule (relocated and renamed Qaanaaq in 1953) in northwest Greenland, facing Canada, where the archaeological remains of the people were first found at Comer’s Midden. The links between the Thule and the Inuit are biological, cultural, and linguistic.

Evidence supports the idea that the Thule (and also the Dorset, but to a lesser degree) were in contact with the Vikings, who had reached the shores of Canada in the 11th century. In Viking sources, these peoples are called the Skræling. Some Thule migrated southward, in the “Second Expansion” or “Second Phase”. By the 13th or 14th century, the Thule had occupied an area currently inhabited by the Central Inuit, and by the 15th century, the Thule replaced the Dorset. Intensified contacts with Europeans began in the 18th century. Compounded by the already disruptive effects of the “Little Ice Age” (1650–1850), the Thule communities broke apart, and the people were henceforward known as the Eskimo, and later, Inuit.

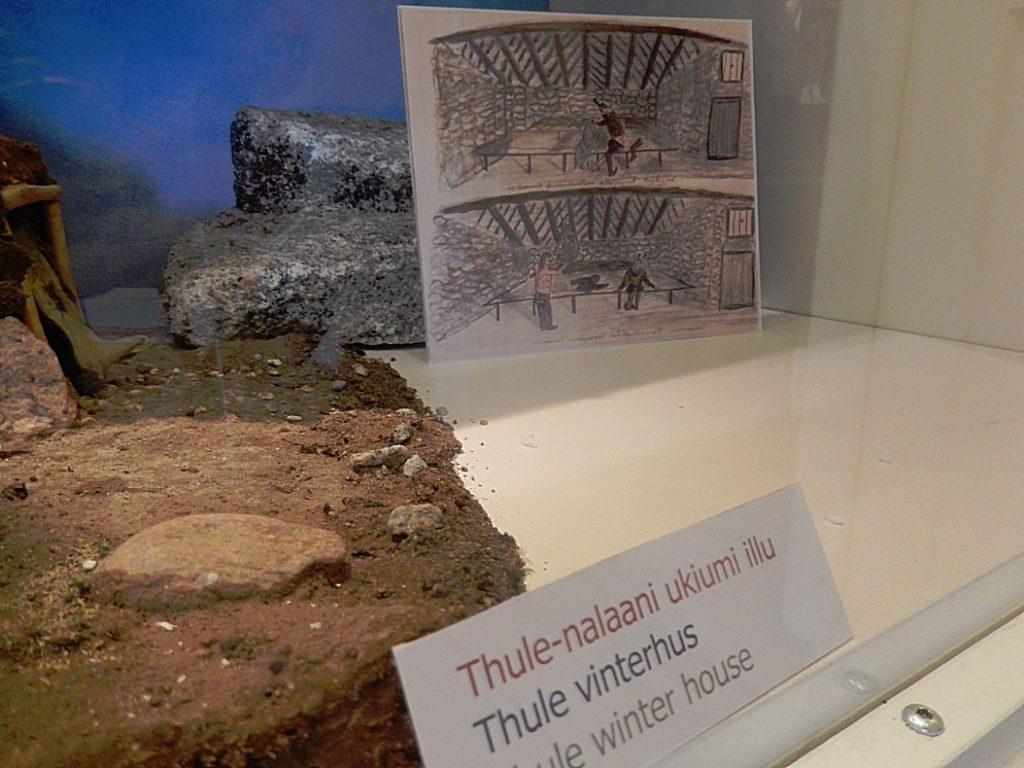

Thule Winter house

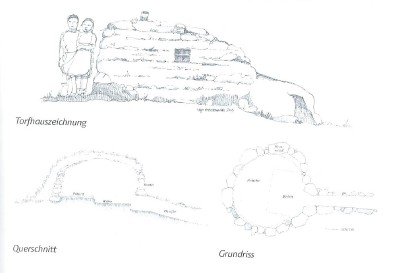

Some drawings showing us how the houses in the Thule culture timespan were build:

Some drawings showing us how the houses in the Thule culture timespan were build:

Finished house

Inuit hunters and Fishermen

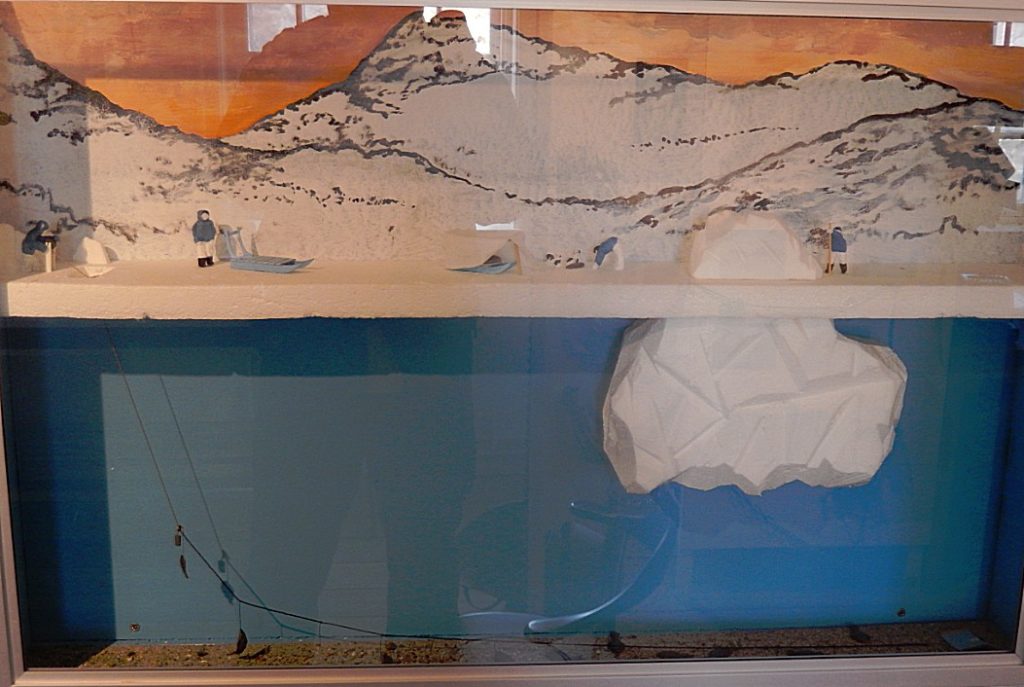

The Inuit people brought with them their techniques and means for hunting and fishing. The village of Sermermiut just south of Ilulissat was located next to the Kangia Icefjord and its settlers used this icefjord which attracted plenty of fish andsea mammals for hunting and fishing.

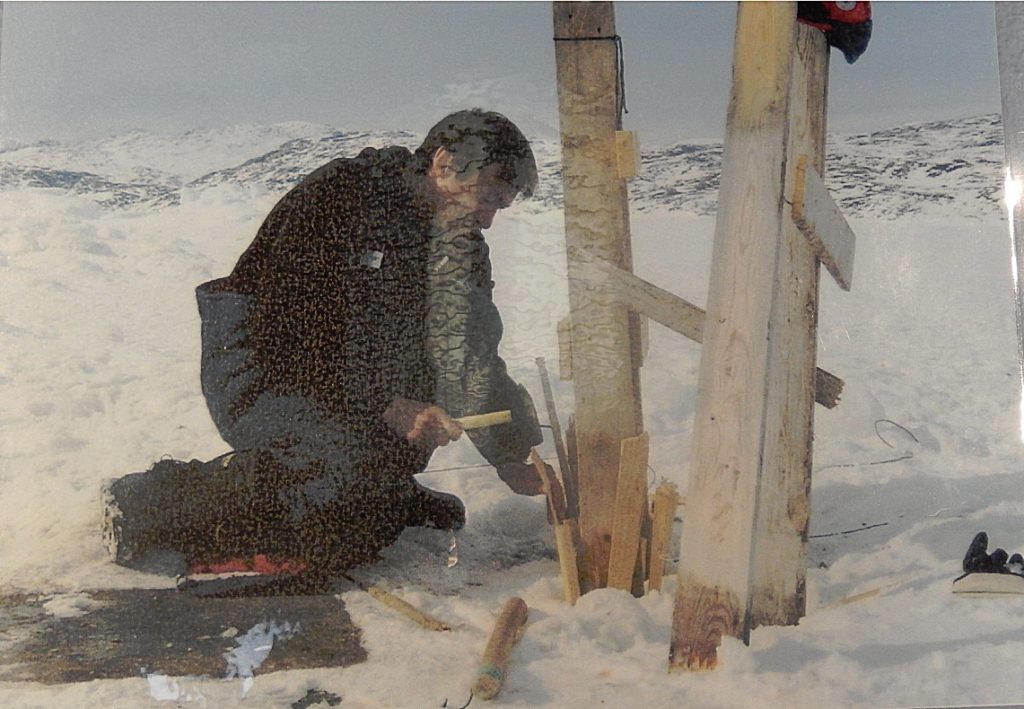

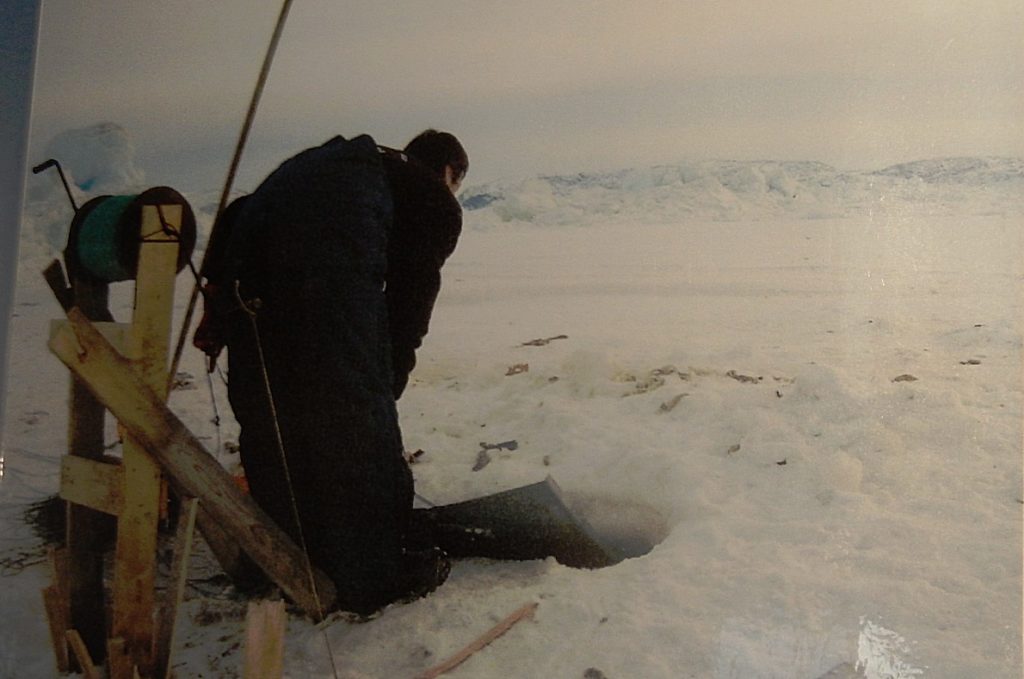

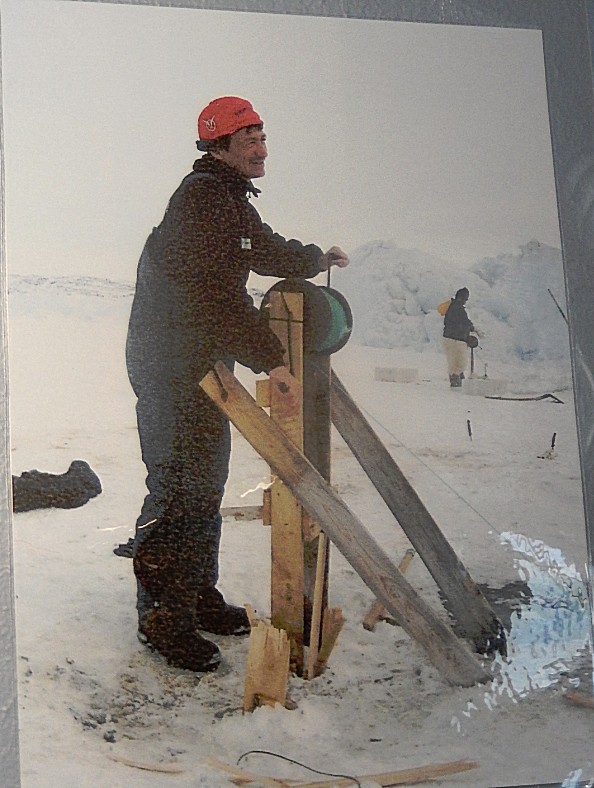

This often meant hunting and fishing on and underneath the ice. A long wire with hooks and bait is used to catch fish.

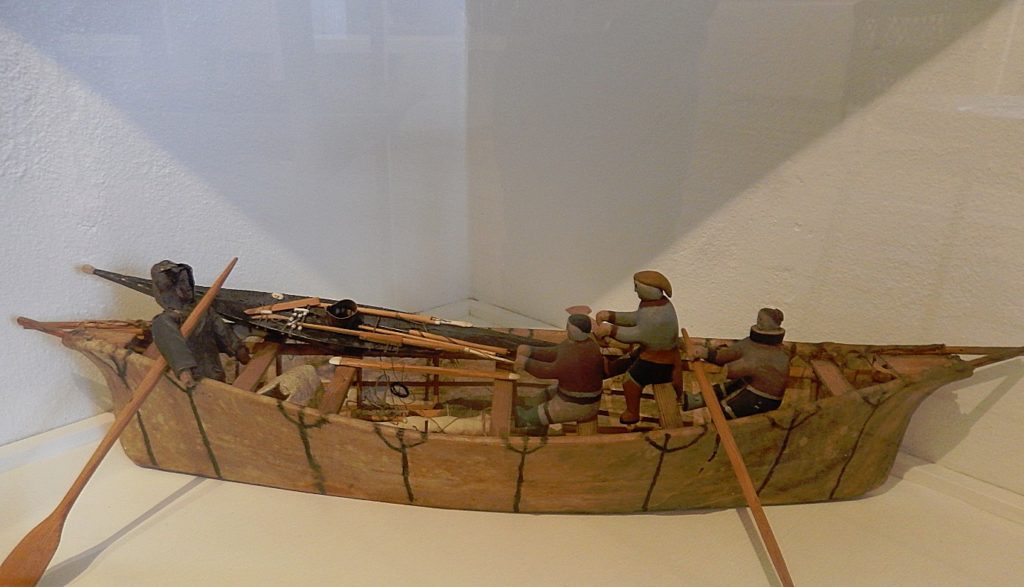

In the beautiful scale model above and in the pics below, these techniques are shown.

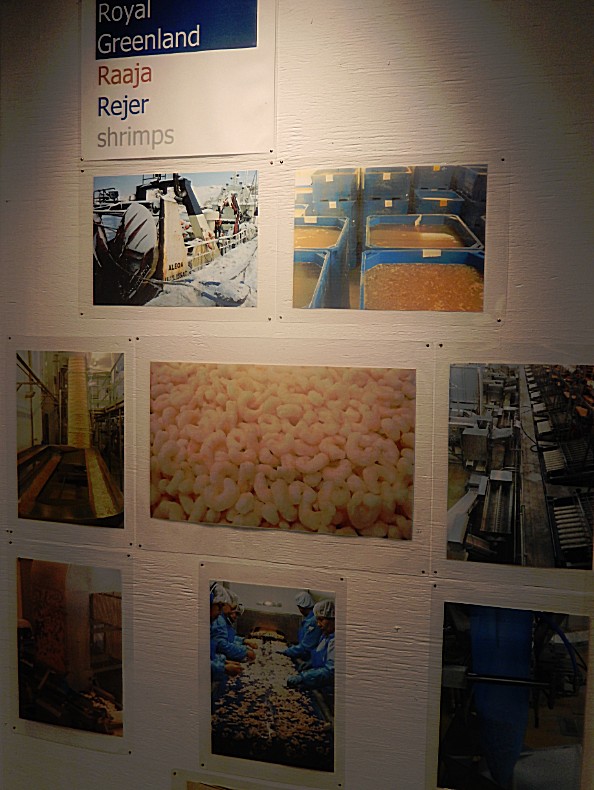

Nowadaysfish and shrimps are caught on a large scale by boats that deliver their catch to the fish factories of e.g. Royal Greenland…

Nowadaysfish and shrimps are caught on a large scale by boats that deliver their catch to the fish factories of e.g. Royal Greenland…

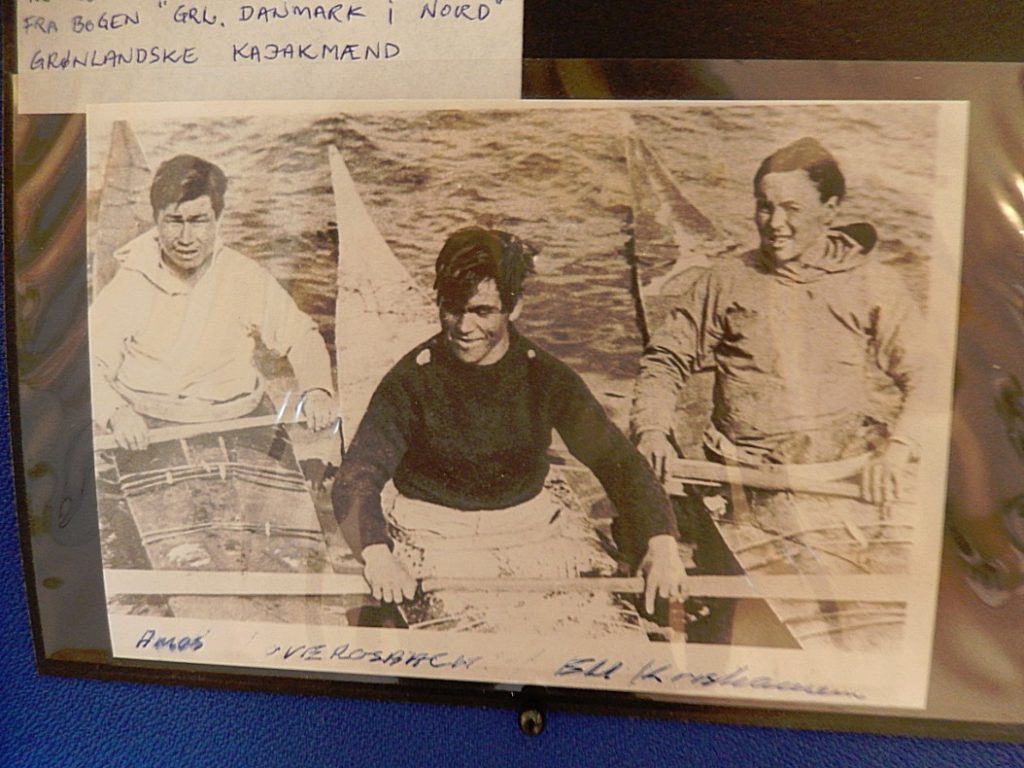

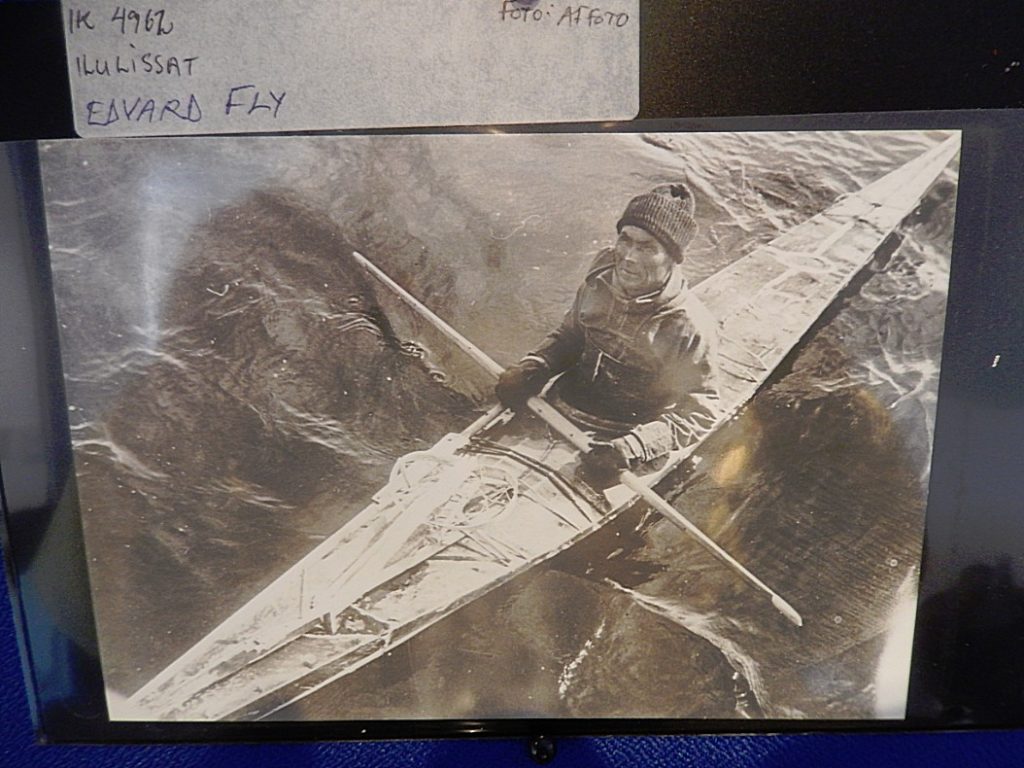

Kayaks and harpoons

Kayaks and harpoons

A kayak is a small, narrow watercraft which is typically propelled by means of a double-bladed paddle. The word kayak originates from the Greenlandic word qajaq.

A kayak is a small, narrow watercraft which is typically propelled by means of a double-bladed paddle. The word kayak originates from the Greenlandic word qajaq.

The traditional kayak has a covered deck and one or more cockpits, each seating one paddler. The cockpit is sometimes covered by a spray deck that prevents the entry of water from waves or spray, differentiating the craft from a canoe. The spray deck makes it possible for suitably skilled kayakers to roll the kayak: that is, to capsize and right it without it filling with water or ejecting the paddler.

Some modern boats vary considerably from a traditional design but still claim the title “kayak”, for instance in eliminating the cockpit by seating the paddler on top of the boat (“sit-on-top” kayaks); having inflated air chambers surrounding the boat; replacing the single hull by twin hulls, and replacing paddles with other human-powered propulsion methods, such as foot-powered rotational propellers and “flippers”. Kayaks are also being sailed, as well as propelled by means of small electric motors, and even by outboard gas engines.

After seeing these historic kayaks I can imagine you would like to experienxe this yourself. The good news is that this is very well possible. See my blog on evening kayaking and see Albatros Arctic Circle for kayak excursions/tours and training.

A harpoon is a long spear-like instrument used in fishing, whaling, sealing, and other marine hunting to catch large fish or marine mammals such as whales. It accomplishes this task by impaling the target animal and securing it with barb or toggling claws, allowing the fishermen to use a rope or chain attached to the butt of the projectile to catch the animal. A harpoon can also be used as a weapon. The picture above shows from top to bottom a traditional paddle and 3 different types of harpoon.

Tradition

Where men used kayaks which are agile but instable, women and children used the larger much more stable Umiaq (women’s boat).

The umiak, umialak, umiaq, umiac, oomiac, oomiak, ongiuk, or anyak is a type of open skin boat used by both Yupik and Inuit, and was originally found in all coastal areas from Siberia to Greenland. First arising in Thule times, it has traditionally been used in summer to move people and possessions to seasonal hunting grounds and for hunting whales and walrus. Although the umiak was usually propelled by oars (women) or paddles (men), sails—sometimes made from seal intestines—were also used, and in the 20th century, outboard motors. Because the umiak has no keel, the sails cannot be used for tacking.

The umiak, umialak, umiaq, umiac, oomiac, oomiak, ongiuk, or anyak is a type of open skin boat used by both Yupik and Inuit, and was originally found in all coastal areas from Siberia to Greenland. First arising in Thule times, it has traditionally been used in summer to move people and possessions to seasonal hunting grounds and for hunting whales and walrus. Although the umiak was usually propelled by oars (women) or paddles (men), sails—sometimes made from seal intestines—were also used, and in the 20th century, outboard motors. Because the umiak has no keel, the sails cannot be used for tacking.

Outside of the museum an Umiaq (which is much larger than a kayak/qayaq) was exhibited in the garden.

One dogsled was in the museum…

One dogsled was in the museum…

Knud Rasmussen used sleds like this to journey accross Canada and Alaska…

At festive days the Inuit people dress in traditional cloths…

There is this stoty about why the men’s clothes on festive days are white. This would prevent the men from secretly gong on a hunt or fishing trip that day, because if they did, chances are huge that mud or blood could be seen on the virgin white clothes and the women would immediately know they had been disobedient.

The retreating Ice

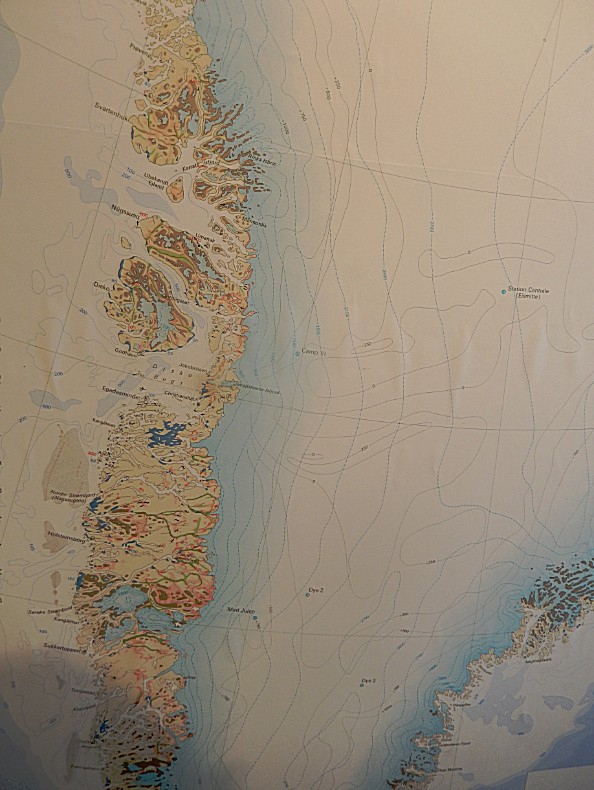

The map below show the altitudes on Greenland and the area around Disko Bay.

The second map shows the retreating glacier at the Kangia icefjord from 2007 back in time to 6000 BC …

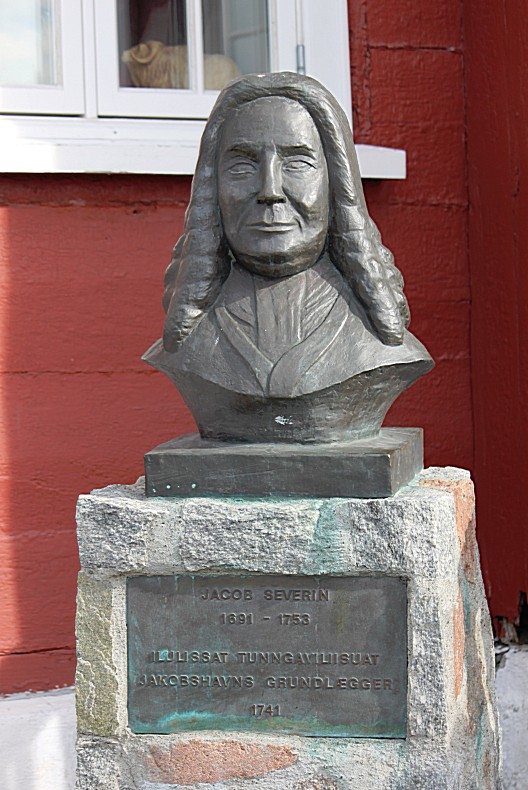

Jacob Severin

Jacob Severin

Biography

He was born in Sæby, Denmark, to Søren Nielsen (c. 1655–1730) and his wife Birgitte Ottesdatter. His father was later magistrate (byfoged) of the community.

After attending school to the age of 15, he married at age 22 a woman two decades his senior, Maren Nielsdatter, the widow of the merchant Segud Langwagen. Using her capital, Severin took over her former husband’s monopoly over the Icelandic trade with Denmark and built a thriving company specialized on Iceland, Finnmark and whaling off Spitzbergen. As a member of Copenhagen’s 32 Men, he had the right of an audience before the king.

The failure of Hans Egede’s Bergen Company and Claus Paarss’s royal colony in Greenland allowed Severin to convince the new Danish king Christian VI and his council to grant his company a full monopoly over trade with the Greenland settlements, a right Frederick IV had previously withheld for fear of antagonizing the Dutch. The monopoly ran from 1733 and was renewed in 1740. He received the right to fly the Danebrog in 1738 and successfully repulsed the Dutch in 1738 and 1739, seizing four of their ships while losing only one of his own. His company was originally underwritten with an annual subsidy of 2000 rixdollars, but this was increased after he petitioned the king in 1740 and claimed to have already lost 16,000 rixdollars on the trade owing to the smallpox epidemic which had decimated the island between 1733 and 1735. Jacobshavn (modern Ilulissat) was named for him, and Poul Egede called him his dearest friend.

Severin married the second time in 1735 to Birgitte Sophie Nygaard of Resen (1704–1739). The same year he purchased Dronninglund Castle from Carl Adolph von Pless. The estate included a forest subsequently used to equip his ships. A third marriage in 1742 to his niece Mary Dalager required a royal license.

In 1749, Severin returned the monopoly, which the king then bestowed on the General Trade Company. Severin then focused his business on trade with Norway. Owing to his friendship with the missionary Paul Egede, however, Severin remained connected to the Greenland mission work throughout his life.

Jacob Severin was one of the most respected, influential and wealthy merchants of Copenhagen. He died on 21 March 1753 at Dronninglund Castle, his estate valued at 9,000 rixdollars, and was buried in Dronfield Church.

This was my last blog of my stay in wonderful Ilulissat and I really learned to love this beautiful town on the shores of Disko Bay…

However this was not the end of my travels through Greenland 🙂