2. Zimbabwe: Victoria Falls National Park: ‘Dr. Livingstone I presume?’ – 2015

After having spend the mayor part of the morning and the early afternoon in Zambia, The Wandelgek decided to spend all afternoon in Zimbabwe. From the border it was a short walk towards the entrance of the Victoria Falls National Park and after paying a steep entrance fee (higher than the Zambian entrance fee to the falls), he walked through a dense but small piece of tropical rain forest, which was only here because the Falls were here. In this forest lived baboons which had learned how to steal food or other shiny bling objects from tourists. They were not afraid of people at all.

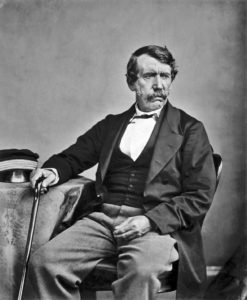

Dr. David Livingstone

David Livingstone (19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish Congregationalist pioneer medical missionary with the London Missionary Society and an explorer in Africa, one of the most popular national heroes of the late-19th-century in Victorian Britain. He had a mythical status that operated on a number of interconnected levels: Protestant missionary martyr, working-class “rags-to-riches” inspirational story, scientific investigator and explorer, imperial reformer, anti-slavery crusader, and advocate of commercial and colonial expansion.

David Livingstone (19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish Congregationalist pioneer medical missionary with the London Missionary Society and an explorer in Africa, one of the most popular national heroes of the late-19th-century in Victorian Britain. He had a mythical status that operated on a number of interconnected levels: Protestant missionary martyr, working-class “rags-to-riches” inspirational story, scientific investigator and explorer, imperial reformer, anti-slavery crusader, and advocate of commercial and colonial expansion.

His fame as an explorer and his obsession with discovering the sources of the River Nile was founded on the belief that if he could solve that age-old mystery, his fame would give him the influence to end the East African Arab-Swahili slave trade. “The Nile sources,” he told a friend, “are valuable only as a means of opening my mouth with power among men. It is this power which I hope to remedy an immense evil.” His subsequent exploration of the central African watershed was the culmination of the classic period of European geographical discovery and colonial penetration.

His fame as an explorer and his obsession with discovering the sources of the River Nile was founded on the belief that if he could solve that age-old mystery, his fame would give him the influence to end the East African Arab-Swahili slave trade. “The Nile sources,” he told a friend, “are valuable only as a means of opening my mouth with power among men. It is this power which I hope to remedy an immense evil.” His subsequent exploration of the central African watershed was the culmination of the classic period of European geographical discovery and colonial penetration.

At the same time, his missionary travels, “disappearance”, and eventual death in Africa—

At the same time, his missionary travels, “disappearance”, and eventual death in Africa—

His meeting with Henry Morton Stanley on 10 November 1871 gave rise to the popular quotation “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”

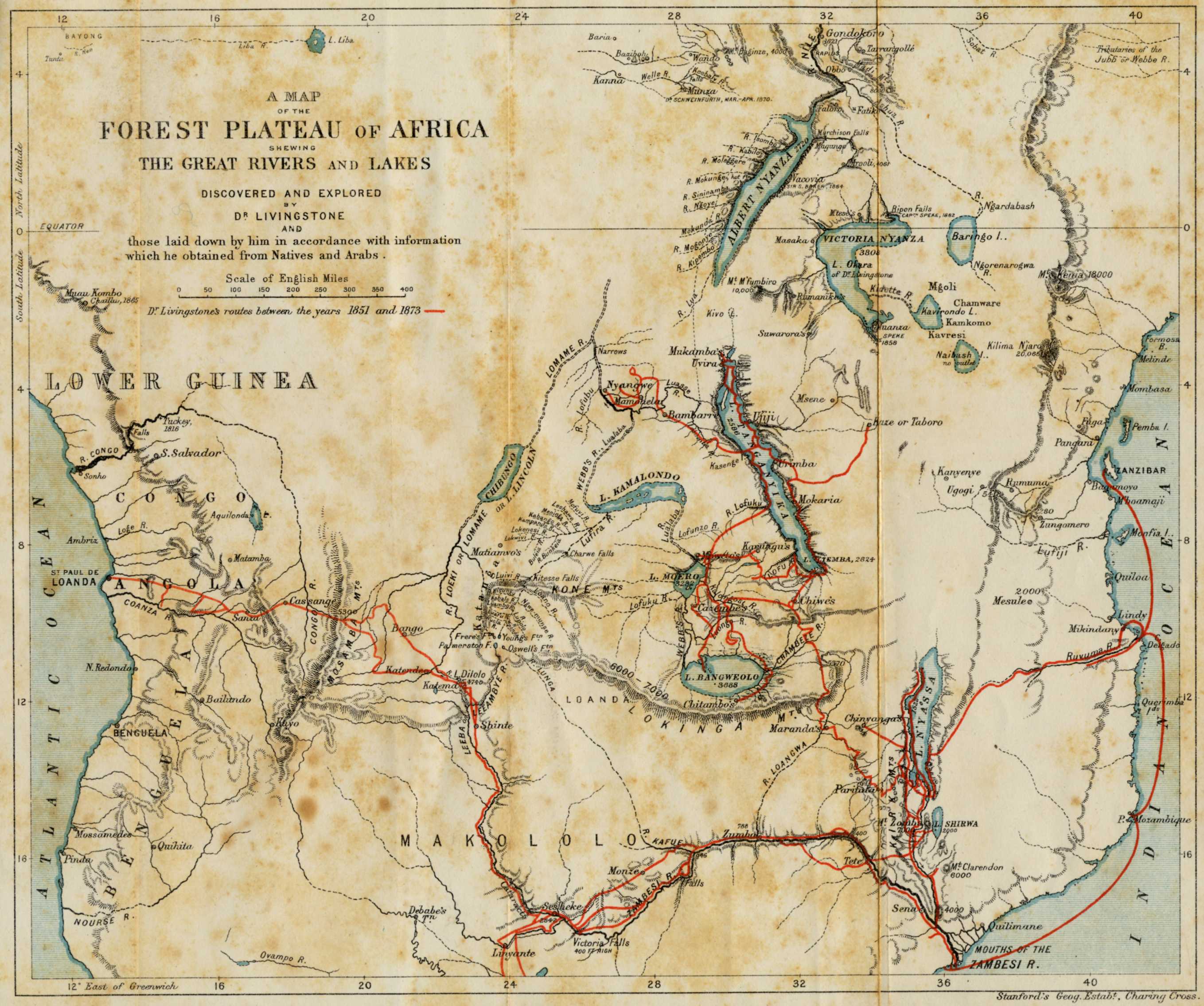

Exploration of southern and central Africa

Livingstone was obliged to leave his first mission at Mabotsa in Botswana in 1845 after irreconcilable differences emerged between himself and his fellow missionary, Rogers [sic] Edwards and because the Bakgatla were proving indifferent to the Gospel. He abandoned Chonuane, his next mission in 1847 because of drought and the proximity of the Boers and his desire “to move on to the regions beyond”. At Kolobeng Mission Livingstone converted Chief Sechele in 1849 after two years of patient persuasion, but only a few months later Sechele lapsed. In 1851, when Livingstone finally left Kolobeng, he did not use this failure to explain his departure, although it played an important part in his decision. Just as important had been the three journeys far to the north of Kolobeng which he had undertaken between 1849 and 1851 and which had left him convinced that the best long term chance for successful evangelising was to open up Africa to European traders and missionaries by mapping and navigating its rivers which might then become “Highways” into the interior. So Livingstone explored the African interior to the north between 1852 and 1856, mapping almost the entire course of the Zambezi, and was the first European to see the Mosi-oa-Tunya (“the smoke that thunders”) waterfall, which he renamed Victoria Falls after his monarch Queen Victoria, and of which he wrote later, “Scenes so lovely must have been gazed upon by angels in their flight.” (Jeal, p. 149)

Livingstone was one of the first Westerners to make a transcontinental journey across Africa in 1854–56, from Luanda on the Atlantic to Quelimane on the Indian Ocean near the mouth of the Zambezi. Central and southern Africa had not been crossed by Europeans at that latitude, despite repeated European attempts (especially by the Portuguese), owing to their susceptibility to malaria, dysentery, and sleeping sickness which was prevalent in the interior and which also prevented use of draught animals (oxen and horses). Such journeys had also been hindered by the opposition of powerful chiefs and tribes, such as the Lozi, and the Lunda of Mwata Kazembe.

The qualities and approaches which gave Livingstone an advantage as an explorer were that he usually travelled light, and he had an ability to reassure chiefs that he was not a threat. Other expeditions had dozens of soldiers armed with rifles and scores of hired porters carrying supplies, and were seen as military incursions or were mistaken for slave-raiding parties. Livingstone, on the other hand, travelled on most of his journeys with a few servants and porters, bartering for supplies along the way, with a couple of guns for protection. He preached a Christian message but did not force it on unwilling ears; he understood the ways of local chiefs and successfully negotiated passage through their territory, and was often hospitably received and aided, even by Mwata Kazembe. His great trans-Africa journey was performed with the help at first of 27 Africans loaned to him by Sekeletu, chief of the Kololo, for the trip to Loanda (Luanda) on the Atlantic Ocean from Linyanti, and with 114 men, loaned by the same chief, on certain conditions, for the last leg of the journey from Linyanti to Quelimane on the Indian Ocean.

Livingstone advocated the establishment of trade and religious missions in central Africa, but abolition of the African slave trade, as carried out by the Portuguese of Tete and the Arab Swahili of Kilwa, became his primary goal. His motto—now inscribed on his statue at Victoria Falls—was “Christianity, Commerce and Civilization“, a combination that he hoped would form an alternative to the slave trade, and impart dignity to the Africans in the eyes of Europeans. He believed that the key to achieving these goals was the navigation of the Zambezi River as a Christian commercial highway into the interior. He returned to Britain to garner support for his ideas, and to publish a book on his travels which brought him fame as one of the leading explorers of the age.

Livingstone believed that he had a spiritual calling for exploration to find routes for commercial trade which would displace slave trade routes, rather than for preaching. He was encouraged by the response in Britain to his discoveries and support for future expeditions, so he resigned from the London Missionary Society in 1857. According to his Victorian biographer W. Garden Blaikie, the reason was to prevent public concerns that his non-missionary activities such as his scientific work might show the LMS to be “departing from the proper objects of a missionary body”. Livingstone had written to the directors of the society to express complaints about their policies and the clustering of too many missionaries near the Cape Colony, despite the sparse native population. Blaikie, not wishing to offend Livingstone’s relatives, still living in 1880 when his book was published, concealed the real reason why Livingstone left the LMS and the manner of it. In a letter from the directors of the LMS, which Livingstone received at Quelimane, he was congratulated on his journey but was told that the directors were “restricted in their power of aiding plans connected only remotely with the spread of the Gospel”. This brusque rejection of his plan for new mission stations north of the Zambesi and his wider object of opening the interior via the Zambezi, was not enough to make him resign at once. When he was approached by Sir Roderick Murchison, president of the Royal Geographical Society, who put him in touch with the Foreign Secretary, Livingstone said nothing to the LMS directors, even when his leadership of a government expedition to the Zambezi seemed increasingly likely to be funded by the Exchequer. “I am not yet fairly on with the Government,” he told a friend, “but am nearly quite off with the Society (LMS).” And while he negotiated with the government, he deceived the LMS into thinking that he would return to Africa with their mission to the Kololo in Barotseland, which Livingstone had used his national fame to coerce them into initiating against their better judgement. As biographer Tim Jeal shows in Chapter 12 of his biography, the end result would be the death of a missionary and his wife, the death of a second missionary’s wife and the deaths of three children from malaria. Livingstone had suffered over thirty attacks during his journey but had deliberately understated his suffering so not to discourage the LMS from sending missionaries to the Kololo. Consequently the missionaries had set out for a marshy region with wholly inadequate supplies of quinine and they had soon weakened and died.

In May 1857 Livingstone was appointed as Her Majesty’s Consul with a roving commission, extending through Mozambique to the areas west of it.

The River Nile

In January 1866, Livingstone returned to Africa, this time to Zanzibar, and from there he set out to seek the source of the Nile.

In January 1866, Livingstone returned to Africa, this time to Zanzibar, and from there he set out to seek the source of the Nile.

In 2002, The Wandelgek had alreay visited The Livingstone House near Stonetown on Zanzibar…

From this house, many of his expeditions started.

The discovery of Mosi-oa-Tunya

Here follows a cited part from: Livingstone, David, Missionary Travels and Researches In South Africa (1858) describing in Dr. David Livingstone’s own words, his discovery of Mosi-oa-Tunya:

“Sekeletu intended to accompany me, but, one canoe only having come instead of the two he had ordered, he resigned it to me.

“Sekeletu intended to accompany me, but, one canoe only having come instead of the two he had ordered, he resigned it to me.

After twenty minutes’ sail from Kalai we came in sight, for the first time, of the columns of vapor appropriately called ‘smoke,’ rising at a distance of five or six miles, exactly as when large tracts of grass are burned in Africa. Five columns now arose, and, bending in the direction of the wind, they seemed placed against a low ridge covered with trees; the tops of the columns at this distance appeared to mingle with the clouds. They were white below, and higher up became dark, so as to simulate smoke very closely. The whole scene was extremely beautiful; the banks and islands dotted over the river are adorned with sylvan vegetation of great variety of color and form…no one can imagine the beauty of the view from any thing witnessed in England. It had never been seen before by European eyes; but scenes so lovely must have been gazed upon by angels in their flight. The only want felt is that of mountains in the background. The falls are bounded on three sides by ridges 300 or 400 feet in height, which are covered with forest, with the red soil appearing among the trees.

When about half a mile from the falls, I left the canoe by which we had come down thus far, and embarked in a lighter one, with men well acquainted with the rapids, who, by passing down the centre of the stream in the eddies and still places caused by many jutting rocks, brought me to an island situated in the middle of the river, and on the edge of the lip over which the water rolls. In coming hither there was danger of being swept down by the streams which rushed along on each side of the island; but the river was now low, and we sailed where it is totally impossible to go when the water is high. But, though we had reached the island, and were within a few yards of the spot, a view from which would solve the whole problem, I believe that no one could perceive where the vast body of water went; it seemed to lose itself in the earth, the opposite lip of the fissure into which it disappeared being only 80 feet distant. At least I did not comprehend it until, creeping with awe to the verge, I peered down into a large rent which had been made from bank to bank of the broad Zambesi, and saw that a stream of a thousand yards broad leaped down a hundred feet, and then became suddenly compressed into a space of fifteen or twenty yards.

When about half a mile from the falls, I left the canoe by which we had come down thus far, and embarked in a lighter one, with men well acquainted with the rapids, who, by passing down the centre of the stream in the eddies and still places caused by many jutting rocks, brought me to an island situated in the middle of the river, and on the edge of the lip over which the water rolls. In coming hither there was danger of being swept down by the streams which rushed along on each side of the island; but the river was now low, and we sailed where it is totally impossible to go when the water is high. But, though we had reached the island, and were within a few yards of the spot, a view from which would solve the whole problem, I believe that no one could perceive where the vast body of water went; it seemed to lose itself in the earth, the opposite lip of the fissure into which it disappeared being only 80 feet distant. At least I did not comprehend it until, creeping with awe to the verge, I peered down into a large rent which had been made from bank to bank of the broad Zambesi, and saw that a stream of a thousand yards broad leaped down a hundred feet, and then became suddenly compressed into a space of fifteen or twenty yards.

The entire falls are simply a crack made in a hard basaltic rock from the right to the left bank of the Zambesi, and then prolonged from the left bank away through thirty or forty miles of hills. If one imagines the Thames filled with low, tree-covered hills immediately beyond the tunnel, extending as far as Gravesend, the bed of black basaltic rock instead of London mud, and a fissure made therein from one end of the tunnel to the other down through the keystones of the arch, and prolonged from the left end of the tunnel through thirty miles of hills, the pathway being 100 feet down from the bed of the river instead of what it is, with the lips of the fissure from 80 to 100 feet apart, then fancy the Thames leaping bodily into the gulf, and forced there to change its direction, and flow from the right to the left bank, and then rush boiling and roaring through the hills, he may have some idea of what takes place at this, the most wonderful sight I had witnessed in Africa.

The entire falls are simply a crack made in a hard basaltic rock from the right to the left bank of the Zambesi, and then prolonged from the left bank away through thirty or forty miles of hills. If one imagines the Thames filled with low, tree-covered hills immediately beyond the tunnel, extending as far as Gravesend, the bed of black basaltic rock instead of London mud, and a fissure made therein from one end of the tunnel to the other down through the keystones of the arch, and prolonged from the left end of the tunnel through thirty miles of hills, the pathway being 100 feet down from the bed of the river instead of what it is, with the lips of the fissure from 80 to 100 feet apart, then fancy the Thames leaping bodily into the gulf, and forced there to change its direction, and flow from the right to the left bank, and then rush boiling and roaring through the hills, he may have some idea of what takes place at this, the most wonderful sight I had witnessed in Africa.

In looking down into the fissure on the right of the island, one sees nothing but a dense white cloud, which, at the time we visited the spot, bad two bright rainbows on it. From this cloud rushed up a great jet of vapor exactly like steam, and it mounted 200 or 300 feet high; there condensing, it changed its hue to that of dark smoke, and came back in a constant shower, which soon wetted us to the skin…

On the left of the island we see the water at the bottom, a white rolling mass moving away to the prolongation of the fissure, which branches off near the left bank of the river… The walls of this gigantic crack are perpendicular, and composed of one homogeneous mass of rock. The edge of that side over which the water falls is worn off two or three feet, and pieces have fallen away, so as to give it some- what of a serrated appearance. That over which the water does not fall is quite straight, except at the left corner, where a rent appears, and a piece seems inclined to fall off Upon the whole, it is nearly in the state in which it was left at the period of its formation…On the left side of the island we have a good view of the mass of water which causes one of the columns of vapor to ascend, as it leaps quite clear of the rock, and forms a thick unbroken fleece all the way to the bottom. Its whiteness gave the idea of snow, a sight I had not seen for many a day. As it broke into (if I may use the term) pieces of water, all rushing on in the same direction, each gave off several rays of foam, exactly as bits of steel, when burned in oxygen gas, give off rays of sparks. The snow-white sheet seemed like myriads of small comets rushing on in one direction, each of which left behind its nucleus rays of foam.”

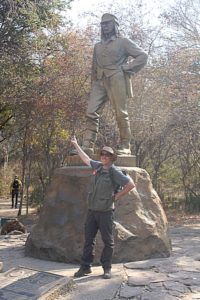

The doctor and The Wandelgek…

Before I started this blogseries and before I started my journey across Southern Africa I wrote a first introductory blog (The Wandelgek on an adventure through Southern Africa) in which I mentioned the importance to experience the sight that Dr. David Livingstone had seen those many years ago in 1855. I wanted to feel a tiny bit of the enormous excitement of what he must have felt.

When I was still in primary school I had read about it and history teachers had read about this in front of classrooms and I had always been completely fascinated and drawn into this specific story. For me it has always been The example story of discovering something new.

And although I don’t dare to compare what he must have endured while travelling from Zanzibar to Mosi-oa-Tunya, with my own travel experiences which were undoubtedly much more comfortable, it still was a very emotional thing to me to reach this part of the world, for which I had longed for so many years and for which I had been preparing in a real practical sense since 2004!

And so I was really impressed to finally stand at the statue of the doctor and even find his canoe (a bit shattered) beside it.

After a short walk The Wandelgek reached the gorge where the mighty Zambezi river (which is Africa’s 4th longest river after the Nile, Congo and Niger) plunges over a 108 metre high and 1,700 metres wide cliff edge.

And yesssss this was very spectacular and I could only think “How is this possible???“…

There was even a double rainbow above the gorge and I could actually see now why the Zambian name Mosi-oa-Tunya was so much better fitting than Victoria Falls. The trillions of tiny drops of water were propelled into the air casing a smoke like curtain that was way higher than the falls themselves. This was also the rain that made the tropical rain forest on the verge of the gorge viable. I couldn’t have been more impressed…

Although… I began to feel the urge to get me a canoe and……….

Victoria Falls, or Mosi-oa-Tunya (Tokaleya Tonga: The Smoke That Thunders), is a waterfall in southern Africa on the Zambezi River at the border of Zambia and Zimbabwe. It has been described by CNN as one of the Seven Natural Wonders of the world.

David Livingstone, the Scottish missionary and explorer, is believed to have been the first European to view Victoria Falls on 16 November 1855, from what is now known as Livingstone Island, one of two land masses in the middle of the river, immediately upstream from the falls on the Zambian side.

Livingstone named his discovery in honour of Queen Victoria of Britain, but the indigenous Tonga name, Mosi-oa-Tunya—”The Smoke That Thunders”—continues in common usage as well. The World Heritage List officially recognizes both names.

The nearby national park in Zambia is named Mosi-oa-Tunya, whereas the national park and town on the Zimbabwean shore are both named Victoria Falls.

Size

While it is neither the highest nor the widest waterfall in the world, Victoria Falls is classified as the largest, based on its combined width of 1,708 metres (5,604 ft) and height of 108 metres (354 ft), resulting in the world’s largest sheet of falling water. Victoria Falls is roughly twice the height of North America’s Niagara Falls and well over twice the width of its Horseshoe Falls. In height and width Victoria Falls is rivalled only by Argentina and Brazil’s Iguazu Falls. See table for comparisons.

For a considerable distance upstream from the falls, the Zambezi flows over a level sheet of basalt, in a shallow valley, bounded by low and distant sandstone hills. The river’s course is dotted with numerous tree-covered islands, which increase in number as the river approaches the falls. There are no mountains, escarpments, or deep valleys; only a flat plateau extending hundreds of kilometres in all directions.

The falls are formed as the full width of the river plummets in a single vertical drop into a transverse chasm 1708 metres (5604 ft) wide, carved by its waters along a fracture zone in the basalt plateau. The depth of the chasm, called the First Gorge, varies from 80 metres (260 ft) at its western end to 108 metres (354 ft) in the centre. The only outlet to the First Gorge is a 110-metre (360 ft) wide gap about two-thirds of the way across the width of the falls from the western end, through which the whole volume of the river pours into the Victoria Falls gorges.

There are two islands on the crest of the falls that are large enough to divide the curtain of water even at full flood: Boaruka Island (or Cataract Island) near the western bank, and Livingstone Island near the middle—the point from which Livingstone first viewed the falls. At less than full flood, additional islets divide the curtain of water into separate parallel streams. The main streams are named, in order from Zimbabwe (west) to Zambia (east): Devil’s Cataract (called Leaping Water by some), Main Falls, Rainbow Falls (the highest) and the Eastern Cataract.

The Zambezi river, upstream from the falls, experiences a rainy season from late November to early April, and a dry season the rest of the year. The river’s annual flood season is February to May with a peak in April. The spray from the falls typically rises to a height of over 400 metres (1,300 ft), and sometimes even twice as high, and is visible from up to 48 km (30 mi) away. At full moon, a “moonbow” can be seen in the spray instead of the usual daylight rainbow. During the flood season, however, it is impossible to see the foot of the falls and most of its face, and the walks along the cliff opposite it are in a constant shower and shrouded in mist. Close to the edge of the cliff, spray shoots upward like inverted rain, especially at Zambia’s Knife-Edge Bridge.

As the dry season takes effect, the islets on the crest become wider and more numerous, and in September to January up to half of the rocky face of the falls may become dry and the bottom of the First Gorge can be seen along most of its length. At this time it becomes possible (though not necessarily safe) to walk across some stretches of the river at the crest. It is also possible to walk to the bottom of the First Gorge at the Zimbabwean side. The minimum flow, which occurs in November, is around a tenth of the April figure; this variation in flow is greater than that of other major falls, and causes Victoria Falls’ annual average flow rate to be lower than might be expected based on the maximum flow.

Gorges

The entire volume of the Zambezi River pours through the First Gorge’s 110-meter-wide (360 ft) exit for a distance of about 150 meters (500 ft), then enters a zigzagging series of gorges designated by the order in which the river reaches them. Water entering the Second Gorge makes a sharp right turn and has carved out a deep pool there called the Boiling Pot. Reached via a steep footpath from the Zambian side, it is about 150 metres (500 ft) across. Its surface is smooth at low water, but at high water is marked by enormous, slow swirls and heavy boiling turbulence. Objects—and humans—that are swept over the falls, including the occasional hippopotamus or crocodile, are frequently found swirling about here or washed up at the north-east end of the Second Gorge. This is where the bodies of Mrs Moss and Mr Orchard, mutilated by crocodiles, were found in 1910 after two canoes were capsized by a hippo at Long Island above the falls. The principal gorges are (see reference for note about these measurements):

- First Gorge: the one the river falls into at Victoria Falls

- Second Gorge: 250 m south of falls, 2.15 km long (270 yd south, 2350 yd long), spanned by the Victoria Falls Bridge

- Third Gorge: 600 m south, 1.95 km long (650 yd south, 2100 yd long), containing the Victoria Falls Power Station

- Fourth Gorge: 1.15 km south, 2.25 km long (1256 yd south, 2460 yd long)

- Fifth Gorge: 2.55 km south, 3.2 km long (1.5 mi south, 2 mi (3.2 km) long)

- Songwe Gorge: 5.3 km south, 3.3 km long, (3.3 mi south, 2 mi (3.2 km) long) named after the small Songwe River coming from the north-east, and the deepest at 140 m (460 ft), the level of the river in them varies by up to 20 meters (65 ft) between wet and dry seasons.

Formation

The recent geological history of Victoria Falls can be seen in the form of the gorges below the falls. The basalt plateau over which the Upper Zambezi flows has many large cracks filled with weaker sandstone. In the area of the current falls the largest cracks run roughly east to west (some run nearly north-east to south-west), with smaller north-south cracks connecting them.

Over at least 100,000 years, the falls have been receding upstream through the Batoka Gorges, eroding the sandstone-filled cracks to form the gorges. The river’s course in the current vicinity of the falls is north to south, so it opens up the large east-west cracks across its full width, then it cuts back through a short north-south crack to the next east-west one. The river has fallen in different eras into different chasms which now form a series of sharply zig-zagging gorges downstream from the falls.

Apart from some dry sections, the Second to Fifth and the Songwe Gorges each represents a past site of the falls at a time when they fell into one long straight chasm as they do now. Their sizes indicate that we are not living in the age of the widest-ever falls.

The falls have already started cutting back the next major gorge, at the dip in one side of the “Devil’s Cataract” (also known as “Leaping Waters”) section of the falls. This is not actually a north-south crack, but a large east-northeast line of weakness across the river, where the next full-width falls will eventually form.

Further geological history of the course of the Zambezi River is in the article of that name.

Pre-colonial history

Archaeological sites around the falls have yielded Homo habilis stone artifacts from 3 million years ago, 50,000-year-old Middle Stone Age tools and Late Stone Age (10,000 and 2,000 years ago) weapons, adornments and digging tools. Iron-using Khoisan hunter-gatherers displaced these Stone Age people and in turn were displaced by Bantu tribes such as the southern Tonga people known as the Batoka/Tokalea, who called the falls Shungu na mutitima. The Matabele, later arrivals, named them aManz’ aThunqayo, and the Batswana and Makololo (whose language is used by the Lozi people) call them Mosi-o-Tunya. All these names mean essentially “the smoke that thunders”.

A map from c. 1750 drawn by Jacques Nicolas Bellin for Abbé Antoine François Prevost d’Exiles marks the falls as “cataractes” and notes a settlement to the north of the Zambezi as being friendly with the Portuguese at the time. Earlier still Nicolas de Fer’s 1715 map of southern Africa has the fall clearly marked in the correct position. It also has dotted lines denoting trade routes that David Livingstone followed 140 years later.

The first European to see the falls was David Livingstone on 17 November 1855, during his 1852–56 journey from the upper Zambezi to the mouth of the river. The falls were well known to local tribes, and Voortrekker hunters may have known of them, as may the Arabs under a name equivalent to “the end of the world”. Europeans were sceptical of their reports, perhaps thinking that the lack of mountains and valleys on the plateau made a large falls unlikely.

Livingstone had been told about the falls before he reached them from upriver and was paddled across to a small island that now bears the name Livingstone Island in Zambia. Livingstone had previously been impressed by the Ngonye Falls further upstream, but found the new falls much more impressive, and gave them their English name in honour of Queen Victoria. He wrote of the falls, “No one can imagine the beauty of the view from anything witnessed in England. It had never been seen before by European eyes; but scenes so lovely must have been gazed upon by angels in their flight.”

In 1860, Livingstone returned to the area and made a detailed study of the falls with John Kirk. Other early European visitors included Portuguese explorer Serpa Pinto, Czech explorer Emil Holub, who made the first detailed plan of the falls and its surroundings in 1875 (published in 1880), and British artist Thomas Baines, who executed some of the earliest paintings of the falls. Until the area was opened up by the building of the railway in 1905, though, the falls were seldom visited by other Europeans. Some writers believe that the Portuguese priest Gonçalo da Silveira was the first European to catch sight of the falls back in the sixteenth century.

History since 1900

Victoria Falls Bridge initiates tourism

European settlement of the Victoria Falls area started around 1900 in response to the desire of Cecil Rhodes’ British South Africa Company for mineral rights and imperial rule north of the Zambezi, and the exploitation of other natural resources such as timber forests north-east of the falls, and ivory and animal skins. Before 1905, the river was crossed above the falls at the Old Drift, by dugout canoe or a barge towed across with a steel cable. Rhodes’ vision of a Cape-Cairo railway drove plans for the first bridge across the Zambezi and he insisted it be built where the spray from the falls would fall on passing trains, so the site at the Second Gorge was chosen. See the main article Victoria Falls Bridge for details. From 1905 the railway offered accessible travel (mainly to whites) from as far as the Cape in the south and from 1909, as far as the Belgian Congo in the north. In 1904 the Victoria Falls Hotel was opened to accommodate (white) visitors arriving on the new railway. The falls became an increasingly popular attraction during British colonial rule of Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) and Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), with the town of Victoria Falls becoming the main tourist centre.

Zambia’s independence and Rhodesia’s UDI

In 1964, Northern Rhodesia became the independent state of Zambia. The following year, Rhodesia unilaterally declared independence. This was not recognized by Zambia, the United Kingdom nor the vast majority of states and led to United Nations-mandated sanctions. In response to the emerging crisis, in 1966 Zambia restricted or stopped border crossings; it did not re-open the border completely until 1980. Guerilla warfare arose on the southern side of the Zambezi from 1972: the Rhodesian Bush War. Visitor numbers began to drop, particularly on the Rhodesian side. The war affected Zambia through military incursions, causing the latter to impose security measures including the stationing of soldiers to restrict access to the gorges and some parts of the falls.

Zimbabwe’s internationally recognised independence in 1980 brought comparative peace, and the 1980s witnessed renewed levels of tourism and the development of the region as a centre for adventure sports. Activities that gained popularity in the area include whitewater rafting in the gorges, bungee jumping from the bridge, game fishing, horse riding, kayaking, and flights over the falls.

Tourism in recent years

By the end of the 1990s almost 400,000 people were visiting the falls annually, and this was expected to rise to over a million in the next decade. Unlike the game parks, Victoria Falls has more Zimbabwean and Zambian visitors than international tourists; the attraction is accessible by bus and train, and is therefore comparatively inexpensive to reach.

The two countries permit tourists to make day trips from each side and visas can be obtained at both border posts. Costs vary from US$45-US$80 (as of 1 December 2013). Visitors with single entry visas are required to purchase a visa each time they cross the border. Frequent changes in visa regulations mean visitors should check the rules before crossing the border.

A famous feature is the naturally formed “Armchair” (now sometimes called “Devil’s Pool”), near the edge of the falls on Livingstone Island on the Zambian side. When the river flow is at a certain level, usually between September and December, a rock barrier forms an eddy with minimal current, allowing adventurous swimmers to splash around in relative safety a few feet from the point where the water cascades over the falls. Occasional deaths have been reported when people have slipped over the rock barrier.

The numbers of visitors to the Zimbabwean side of the falls has historically been much higher than the number visiting the Zambia side, due to the greater development of the visitor facilities there. However, the number of tourists visiting Zimbabwe began to decline in the early 2000s as political tensions between supporters and opponents of president Robert Mugabe increased. In 2006, hotel occupancy on the Zimbabwean side hovered at around 30%, while the Zambian side was at near-capacity, with rates in top hotels reaching US$630 per night. The rapid development has prompted the United Nations to consider revoking the Falls’ status as a World Heritage Site. In addition, problems of waste disposal and a lack of effective management of the falls’ environment are a concern.

Natural environment

National parks

The two national parks at the falls are relatively small—Mosi-oa-Tunya National Park is 66 square kilometres (16,309 acres) and Victoria Falls National Park is 23 square kilometres (5,683 acres). However, next to the latter on the southern bank is the Zambezi National Park, extending 40 kilometres (25 mi) west along the river. Animals can move between the two Zimbabwean parks and can also reach Matetsi Safari Area, Kazuma Pan National Park and Hwange National Park to the south.

On the Zambian side, fences and the outskirts of Livingstone tend to confine most animals to the Mosi-oa-Tunya National Park. In addition fences put up by lodges in response to crime restrict animal movement.

In 2004 a separate group of police called the Tourism Police was started. They are commonly seen around the main tourist areas, and can be identified by their uniforms with yellow reflective bibs.

Vegetation

Mopane woodland savannah predominates in the area, with smaller areas of miombo and Rhodesian teak woodland and scrubland savannah. Riverine forest with palm trees lines the banks and islands above the falls. The most notable aspect of the area’s vegetation though is the rainforest nurtured by the spray from the falls, containing plants rare for the area such as pod mahogany, ebony, ivory palm, wild date palm and a number of creepers and lianas. Vegetation has suffered in recent droughts, and so have the animals that depend on it, particularly antelope.

Wildlife

The national parks contain abundant wildlife including sizable populations of elephant, buffalo, giraffe, Grant’s zebra, and a variety of antelope. Katanga lions, African leopards and South African cheetahs are only occasionally seen. Vervet monkeys and baboons are common. The river above the falls contains large populations of hippopotamus and crocodile. African bush elephants cross the river in the dry season at particular crossing points.

Klipspringers, honey badgers, lizards and clawless otters can be glimpsed in the gorges, but they are mainly known for 35 species of raptors. The Taita falcon, black eagle, peregrine falcon and augur buzzard breed there. Above the falls, herons, fish eagles and numerous kinds of waterfowl are common.

Fish

The river is home to 39 species of fish below the falls and 89 species above it. This illustrates the effectiveness of the falls as a dividing barrier between the upper and lower Zambezi.

Statistics

| Size and flow rate of Victoria Falls with Niagara and Iguazu for comparison | ||||||

| Parameters | Victoria Falls | Niagara Falls | Iguazu Falls | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height in meters and feet: | 108 m | 360 ft | 51 m | 167 ft | 64–82 m | 210–269 ft |

| Width in meters and feet: | 1,708 m | 5,604 ft | 1,203 m | 3,947 ft | 2,700 m | 8,858 ft |

| Flow rate units (vol/s): | m3/s | cu ft/s | m3/s | cu ft/s | m3/s | cu ft/s |

| Mean annual flow rate: | 1,088 | 38,430 | 2,407 | 85,000 | 1,746 | 61,600 |

| Mean monthly flow—max.: | 3,000 | 105,944 | ||||

| Mean monthly flow—min.: | 300 | 10,594 | ||||

| Mean monthly flow—10 yr. max.: | 6,000 | 211,888 | ||||

| Highest recorded flow: | 12,800 | 452,000 | 6,800 | 240,000 | 45,700 | 1,614,000 |