11e. Namibia: Etosha National Park (Day 2 of 3) The pan – 2015

The dry Etosha pan is a 60 by 120 kilometer dry salt lake and if you proceed far enough from the edge, you can’t see anything but a flat white floor.

This is probably the most end of the world like country I’ve ever visited. First the Skeleton Coast in the Namib desert and now the Etosha salt pan in the Kalahari desert. It’s hard to describe this place. I saw animals at the edge of the pan, but the more I drove onwards, the emptier the landscape got. And here I didn’t see anything but saltcrusted mud and blue sky above it. No birds either…

The Etosha pan is a large endorheic salt pan, forming part of the Kalahari Basin in the north of Namibia. The 120-kilometre-long (75-mile-long) dry lakebed and its surroundings are protected as Etosha National Park, one of Namibia’s largest wildlife parks. The pan is mostly dry but after a heavy rain it will acquire a thin layer of water, which is heavily salted by the mineral deposits on the surface of the pan, which most of the year is dry mud coated with salt.

Location and description

Etosha, meaning ‘Great White Place’ is made of a large mineral pan. The area exhibits a characteristic white and greenish surface, which spreads over 4,800[1] km2. The pan developed through tectonic plate activity over about ten million years. Around 16,000 years ago, when ice sheets were melting across the land masses of the Northern Hemisphere, a wet climate phase in southern Africa filled Etosha Lake. Today however the Etosha Pan is mostly dry clay mud split into hexagonal shapes as it dries and cracks, and is seldom seen with even a thin sheet of water covering it.

It is assumed that the Cunene River fed the lake at that time, but tectonic plate movements over time caused a change in river direction, resulting in the lake running dry and leaving a salt pan. Now the Ekuma River is the sole source of water for the lake. Typically, little river water or sediment reaches the dry lake because water seeps into the riverbed along its 250-kilometre (160 mi) course, reducing discharge along the way.

Flora and Fauna

The surrounding area is dense mopane woodland which is occupied by herds of elephants on the south side of the lake. Mopane trees are common throughout south-central Africa, and host the mopane worm, which is the larval form of the moth Gonimbrasia belina, and an important source of protein for rural communities.

The salt desert supports very little plant life except for the blue-green algae that gives the Etosha its characteristic colouring, and grasses like Sporobolus spicatus which quickly grow in the wet mud following a rain. Away from the lake there is grassland that supports grazing animals.

This harsh dry land with little vegetation and small amounts of salty water, when it is present at all, supports little wildlife all year round but is used by a large number of migratory birds. The hypersaline pan supports brine shrimp and a number of extremophile micro-organisms tolerant of the high saline conditions.(C.Michael Hogan. 2010.) In particularly rainy years the Etosha pan becomes a lake approximately 10 cm in depth and becomes a breeding ground for flamingos, which arrive in their thousands, and great white pelican (Pelecanus onocrotalus).

The surrounding savanna is home to a number of mammals that will visit the pan and surrounding waterholes when there is water. These include quite large numbers of zebra (Equus quagga), blue wildebeest (Connocheatus taurinus), gemsbok, eland and springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis) as well as black rhinoceros, elephants, lions, leopards, and giraffe.

Just to show you how the landscape of Etosha looked like when not on the pan I’ll post these few pictures with scrubs and grasses…

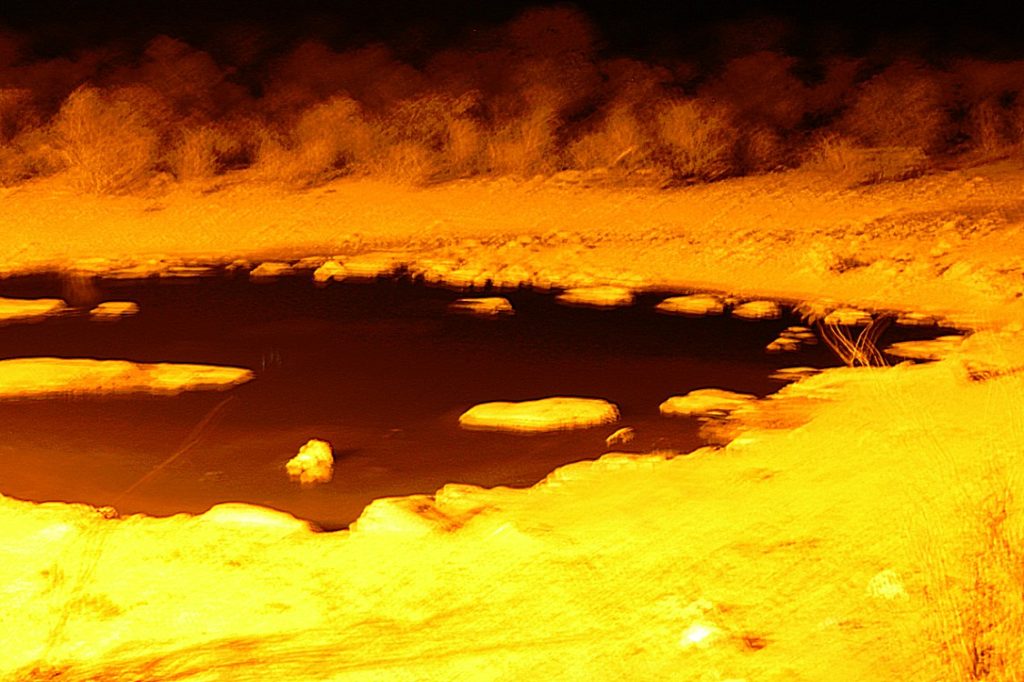

At nightfall The Wandelgek returned at the Halali campsite and after dinner he went to the waterhole to spot some more animals…

Late at the night, the sky was bright because of the billions of stars of the Milky Way shining towards Earth, I went to my cabin to shower and sleep.

Late at the night, the sky was bright because of the billions of stars of the Milky Way shining towards Earth, I went to my cabin to shower and sleep.