9. Damaraland and Kamanjab

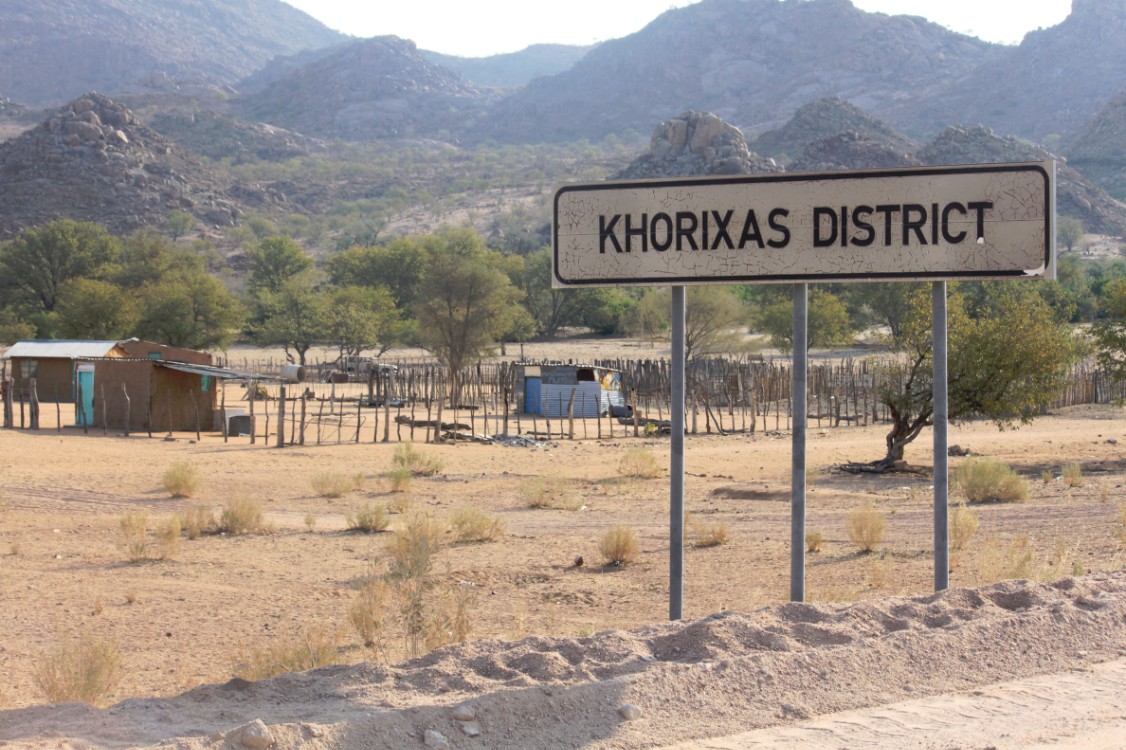

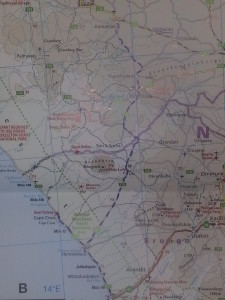

After driving for hours eastward over the wide, flat nothingness that is the Skeleton Coast, a mountain started to grow on the far eastern horizon. It was Brandberg, or Fire mountain, the highest mountain in Namibia. The gravelroad came from the coast and stretched to the north east passing the small village of Uis, east of the Brandberg and then driving further north east in to the Khorixas district where the colourfully dressed Herero tribe lives towards Fransfontein and ultimately Kamanjab.

After driving for hours eastward over the wide, flat nothingness that is the Skeleton Coast, a mountain started to grow on the far eastern horizon. It was Brandberg, or Fire mountain, the highest mountain in Namibia. The gravelroad came from the coast and stretched to the north east passing the small village of Uis, east of the Brandberg and then driving further north east in to the Khorixas district where the colourfully dressed Herero tribe lives towards Fransfontein and ultimately Kamanjab.

Damaraland

Damaraland was a name given to the north-central part of what later became Namibia, inhabited by the Damaras. It was bounded roughly by Ovamboland in the north, the Namib Desert in the west, the Kalahari Desert in the east, and Windhoek in the south.

In the 1970s the name Damaraland was revived for a bantustan in South West Africa (present-day Namibia), intended by the apartheid government to be a self-governing homeland for the Damara people. A centrally administered local government was created in 1980. The bantustan Damaraland was situated on the western edge of the territory that had been known as Damaraland in the 19th century.

Damaraland, like other homelands in South West Africa, was abolished in May 1989 at the start of the transition to independence.

The name Damaraland predates South African control of Namibia, and was described as “the central portion of German South-West Africa” in the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition.

Brandberg Mountain

The Brandberg (Damara: Dâures; Otjiherero: Omukuruvaro), is Namibia’s highest mountain.

Location and extent

Brandberg Mountain is located in Damaraland, in the northwestern Namib Desert, near the coast, and covers an area of approximately 650 km². With its highest point, the Königstein (German for ‘King’s Stone’), standing at 2,606 m (8,550 ft) above sea level and located on the flat Namib gravel plains, on a clear day ‘The Brandberg’ can be seen from a great distance. There are various routes to the summit, the easiest (also steepest) being up the Ga’aseb river valley, but other routes include the Hungurob and Tsisab river valleys. The nearest settlement is Uis, roughly 30 km from the mountain.

Origin of name

The name Brandberg is Afrikaans, Dutch and German for Fire Mountain, which comes from its glowing color which is sometimes seen in the setting sun. The Damara name for the mountain is Dâures, which means ‘burning mountain’, while the Herero name, Omukuruvaro means ‘mountain of the Gods’.

Geology

The Brandberg Massif or Brandberg Intrusion is a granitic intrusion, which forms a dome-shaped massif. It originated during Early Cretaceous rifting that led to the opening of the South Atlantic ocean. Argon–argon dating yielded intrusive ages of 132 to 130 Ma. The dominant plutonic rock is a homogeneous medium grained biotite-hornblende granite. In the western interior of the massif (Naib gorge), a 2 km in diameter body of pyroxene-bearing monzonite is exposed. The youngest intrusive rocks based on cross-cutting relations are arfvedsonite granite dikes and sills in the southwestern periphery of the Brandberg massif which crop out in the Amis valley. The arfvedsonite granites contain minerals rich in rare earth element minerals such as pyrochlore and bastnaesite. Remnants of Cretaceous volcanic rocks are preserved in a collar along the western and southern margins of the massif. Their angle of dip increases towards the contact where clasts of country-rock occur within the granite forming a magmatic breccia. The origins of the magmas that formed the Brandberg intrusion are related to emplacement of mantle-derived basaltic magma during continental break-up which led to partial melting of crustal rocks resulting in a hybrid granitic magma. Erosion subsequently removed the overburden rock. Apatite fission track dating indicates approximately 5 km denudation between 80 and 60 Ma.

An associated feature is the Doros Complex.

Rock painting

The Brandberg is a spiritual site of great significance to the San (Bushman) tribes. The main tourist attraction is The White Lady rock painting, located on a rock face with other art work, under a small rock overhang, in the Tsisab Ravine at the foot of the mountain. The ravine contains more than 1 000 rock shelters, as well as more than 45 000 rock paintings.

To reach The White Lady it is necessary to hike for about 40 minutes over rough terrain, along the ancient watercourses threading through the mountain.

The higher elevations of the mountain contain hundreds of further rock paintings, most of which have been painstakingly documented by Harald Pager, who made tens of thousands of hand copies. Pager’s work was posthumously published by the Heinrich Bart Institute, in the six volume series “Rock Paintings of the Upper Brandberg” edited by Tilman Lenssen-Erz. (I. Amis Gorge, II. Hungorob Gorge, III. Southern Gorges (Ga’aseb & Orabes), IV. Umuab & Karoab Gorges, V. Naib (A)and the Northwest, VI. Naib (B), Circus & Dom Gorges. Volume VII. Numas Gorge is unlikely to be published due to discontinued funding.)

Wildlife

The Brandberg is also home to some interesting desert flora. Damaraland is well known for its grotesque aloes and euphorbias and the region around the mountain is no exception. The area has many plants and trees that have an alien appearance, due in part to the extreme climatic conditions.

The area is uninhabited and wild. It is very arid and finding water can be difficult or impossible. In summer temperatures over 40 °C are routine.

Nonetheless, the Brandberg area is home to a large diversity of wildlife. The numbers of animals are small because the environment cannot support large populations, however most of the desert species that are found in Namibia are present and visitors to the area might glimpse a desert dwelling elephant or a rare black rhino.

The new insect taxon Mantophasmatodea was first discovered on this mountain in 2002.

The scorpion fauna of the Brandberg massif is probably the richest in southern Africa.

Flora of Namibia

The Brandberg lies within the Karroo-Namib floristic region and few members of the Cape flora are represented. A checklist of 357 species was published in 1974 by Bertil Nordenstam stating that 11 taxa are endemic to the Brandberg, with a further 28 species endemic to the Kaoko element. A large and significant group of species has a disjunction between the Karroo-Namib region in the south, and the arid parts of north-east Africa. These appear to be remnants of a hypothesised arid-track joining the two areas.

World Heritage status

The Brandberg National Monument Area was added to the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List on 3 October 2002 in the Mixed (Cultural + Natural) category.

Herero people

The Herero is an ethnic group inhabiting parts of Southern Africa. The majority reside in Namibia, with the remainder found in Botswana and Angola. There were an estimated 250,000 Herero people in Namibia in 2013. They speak the Herero language, which belongs to the Bantu languages.

Unlike most Bantus, who are primarily subsistence farmers, the Herero are traditionally pastoralists and make a living tending livestock. Cattle terminology in use among many Bantu pastoralist groups testifies that Bantu herders originally acquired cattle from Cushitic pastoralists inhabiting Eastern Africa. After Bantus settled in Eastern Africa, some Bantu tribes spread south. Linguistic evidence also suggests that Bantus borrowed the custom of milking cattle from Cushitic peoples; either through direct contact with them or indirectly via Khoisan intermediaries who had themselves acquired both domesticated animals and pastoral techniques from Cushitic migrants.

The Herero claim to comprise several sub-divisions, including the Himba, the Tjimba (Cimba), the Mbanderu and the Kwandu. Groups in Angola include the Mucubal Kuvale, Zemba, Hakawona, Tjavikwa, Tjimba and Himba, who regularly cross the Namibia/Angola border when migrating with their herds. However, the Tjimba, though they speak Herero, are physically distinct indigenous hunter-gatherers; it may be in the Herero’s interest to portray indigenous peoples as impoverished (cattleless) Herero.

The leadership of the Ovaherero is distributed over eight royal houses, among them:

- Maharero Royal Traditional Authority, chief Tjinaani Maharero

- Zeraeua Royal Traditional Authority at Otjimbingwe

- Ovambanderu Royal Traditional Authority, chief Kilus Karaerua Nguvauva

- Onguatjindu Royal Traditional Authority at Okakarara, chief Sam Kambazembi

Since conflicts with the Nama people in the 1860s necessitated Ovaherero unity, they also have a paramount chief ruling over all eight royal houses, although there is currently an interpretation that such paramount chieftaincy violates the Traditional Authorities Act, Act 25 of 2000.

Kamanjab

Kamanjab (Otjiherero name: Okamanja) is a village and a constituency in the Kunene region in Namibia. It has a population of 6,012 and is governed by a village council that currently has five seats.

In Kamanjab the night was spent in a very good, high quality hotel. The hotel had a German owner and the waitresses we’re very cheerful and friendly. The rooms were all situated around a courtyard and were basic but fine and the dinner was served outside in the courtyard. After dinner a group of local childeren of the Kamanjab youth choir gave a great performance singing and dancing.

The next day, The Wandelgek left Kamajab early and the truck drove through Kaokoland, country of the Himba tribe.

Kaokoland

Kaokoland is an area in Northern Namibia, in the Kaokoveld Region. It is one of the wildest and least populated areas in Namibia, with a population density of one person every 2 km², that is 1/4 of the national average. The most represented ethnic group is the Himba people, that accounts for about 5,000 of the overall 16,000 inhabitants of Kaokoland. The main settlement in Kaokoland is the city of Opuwo.

Kaokoland used to be a bantustan of South West Africa during the apartheid era. While it was intended to be a self-governing Himba homeland, an actual government was never established. Like other homelands in South West Africa, the Kaokoland bantustan was abolished in May 1989, at the beginning of the transition of Namibia towards independence. “Kaokoland” remained as an informal name for the geographic area.

Geography

The Kaokoland area extends south-north from the Hoanib river to the Kunene river (that also marks the border between Namibia and Angola). It is largely mountainous, with the northern Baynes Mountains reaching the maximum elevation at 2039 m. Other notable mountain ranges of Kaokoland include the Otjihipa Mountains (to the north) and the Hartmann Mountains (to the east). The land is generally dry and rocky, especially to the south, where it borders on the Namib Desert; nevertheless, it has several rivers as well as falls. The most notable falls in Kaokoland are the Ruacana Falls (120 m high, 700 m wide) and the Epupa Falls, both formed by the Kunene river. The northern part of Kaokoland is greener, with vegetation thriving valleys such as the Marienfluss and Hartmann Valley.

History

Before colonialism, Kaokoland was mostly inhabited by the Ovambo, Nama, and Herero people. In the second half of the 19th century, a group of Herero crossed the Kunene River, migrating north to what is now Angola, joining with the Bushmen in Southern Angola; the modern day Himba people originated from this Angolan Herero group. In 1884, Kaokoland became part of German South-West Africa, and Namibian Herero changed much of their habits and costumes as a consequence of German rule. After World War I, South Africa received the mandate from the League of Nations to administer the territory of Namibia, which became, for all practical purposes, a province of South Africa. South Africa also applied to Namibia the principles of apartheid, including the creation of distinct bantustans (homelands) for different African ethnic groups. Kaokoland was thus established as a bantustan for the Himba people, that in the 1920s had come back from Angola into Namibia. Despite its scarce population, Kaokoland was greatly affected by the struggle for independence of Namibia, and most specifically by the so-called “bush war” that was fought across the border with Angola (i.e., in Kaokoland).

The Himba people

The Himba people are the descendants of a Herero group that got isolated from the others in the 19th century. While the Herero people later experienced German rule and drastically changed their lifestyle as well as their costumes, the Himba retained much of their traditional, nomadic and pastoral habits. In recent times, contacts between Himbas and Western tourists are becoming more and more common, especially in the most easily accessible regions of Kaokoland (e.g., the surroundings of Opuwo). While this has partially affected the Himba culture, Himbas have essentially remained faithful to their tradition.

Fauna

Fauna in Kaokoland suffered from a severe crippling between 1977 and 1982, as well as from poaching throughout the 1970s, but has been recovering afterwards. It includes several desert-dwelling species, most notably a population of desert elephants that are sometimes classified as a distinct subspecies of African elephants because of their shorter legs and specific, desert-adapted behaviour (the only other place in Africa where elephants have adapted to a desert environment is Mali, on the border of the Sahara desert). Its longer legs, bigger feet, and incredible ability to withstand periods of drought all gave valid reasons to think so. Today, however, it is not considered a different species, rather regarded as only ‘desert adapted.’ The herds in this area remain separate from other elephant herds in Namibia and only appear to have longer legs and bigger feet because they eat less than elephants living in more food abundant areas such as Etosha National Park, the Caprivi, and Chobe region in Botswana.

The desert elephant are truly incredible survivalists, claiming a three-thousand square kilometre range and regularly travelling up to two hundred kilometres in search of water. They only drink every three or four days, compared with elephant in Etosha drinking one-hundred to two-hundred litres of water a day. They also seem to be more environmentally conscious than other elephants: Unlike other elephants, the desert adapted elephant rarely knock over trees, break branches, or tear away bark, as if knowing that doing so would endanger their food.

They are commonly roaming the dry riverbeds of the westward flowing Huab, Hoanib, Hoarusib, and Khumib rivers. It is along these riverbeds the animals find the occasional spring fed waterhole and most of their nutrient rich foods: mopane bark, tamarisk, reeds, and the pods, bark, and leaves of the ana tree. On a typical day, desert elephants travel up to sixty kilometres over rocky, difficult terrain between feeding areas and waterholes. When water is truly scarce, as in times of drought, they dig holes, commonly known as gorras, in the dry riverbeds. Water seeps up from below the surface creating a much needed water source for themselves, and other animals in the area; unlike other elephants, which drink daily, desert elephants have been known to survive without water for up to four days.

Black rhinos were extinguished in the area in 1983, but they have been reintroduced. Other species found in Kaokoland include oryxes, kudus, springboks, ostrichs, giraffes and mountain zebras.

Tourism and transportation

After the end of the bush war, Kaokoland has become a common tourist destination in Namibia, due its proximity to the Etosha National Park (to the south), the unspoiled nature (with several spots suitable for activities such as rafting and trekking), and the opportunity to visit traditional Himba villages. Notable landmarks in the area include the Epupa Falls, Sesfontein, Himba villages, and the Ondurusa Rapids.

Kaokoland is one of the wildest regions of Southern Africa, with very few roads and structures. The only road that is accessible to non-4WD vehicles is that connecting Sesfontein and Opuwo. Many roads in Kaokoland are often in very bad conditions and may be challenging for 4WDs as well, especially during the rainy season. Most services such as shops, hospital, garage, and so on are only found in Opuwo.

where the night was spent in a very good, high quality hotel. The hotel had a German owner and the waitresses we’re very cheerful and friendly. The rooms were all situated around a courtyard and were basic but fine and the dinner was served outside in the courtyard. After dinner a group of local childeren of the Kamanjab youth choir gave a great performance singing and dancing.