6. Skeleton Coast north of Swakopmund: Discovering the living desert

The Namib desert mostly consists of flat barren land covered in sand with some sand dunes scattered near the coast. It seems nothing can live there but actually there’s a lot of wildlife to find. North of Swakopmund we drove in two 4 wheel drive suv’s and there we left the road and drove all morning through the Namib desert (here named Skeleton Coast) searching for the little five. The little five are five small desert animals as opposed to the big five which are five safari animals.

We had two guides who new this desert very well and who could tell us about the animals, the plants and about the shapes of the dunes…

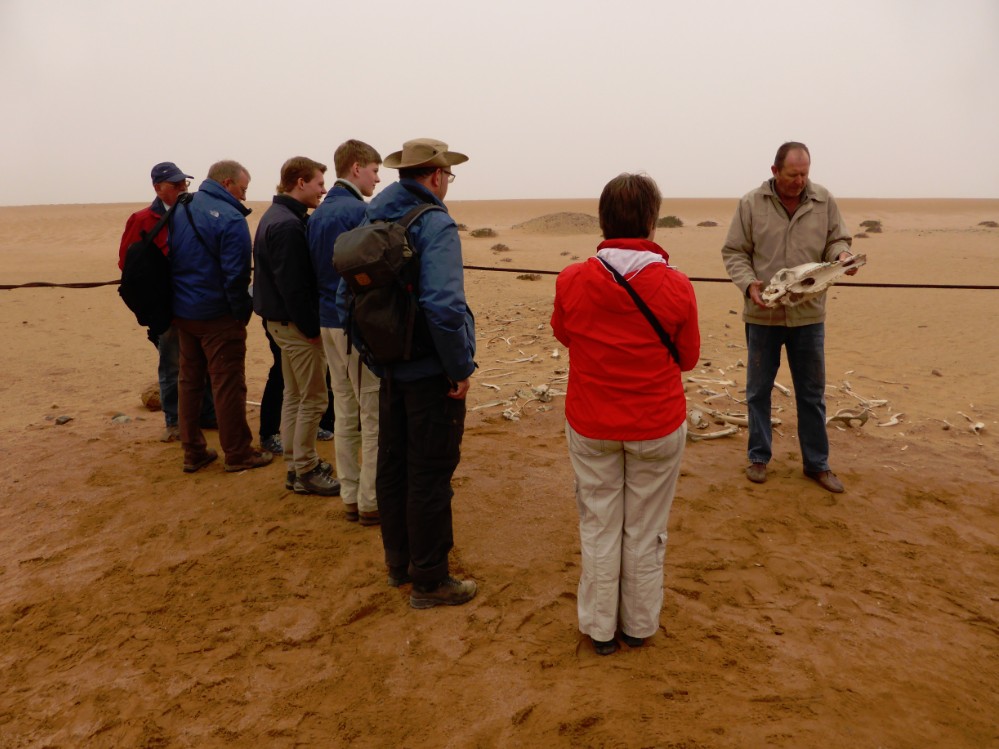

Horse graves near Swakopmund

For a long time enormous masses of horse bones have been found in the dunes a few kilometres outside of coastal town Swakopmund, western Namibia. Only a limited number of people, usually 4×4 drivers or dune quad bikers have come across the long rows of white horse skulls and bones in the dune valleys about 4 km to the south of the Swakop river. Many of them have wondered about the origin and the story surrounding them. The most mysterious fact is that the skulls have a bullet hole in the forehead.

The most popular theory or version that has been common for a long time is that the horses were used by a German Schutztruppe during World War 1 and that they died of unknown horse disease. Other versions include opinions that the horses died of food poisoning or lack of food/water. But why does every skull have a bullet hole? Were they German Schutztruppe horses or horses of South African Occupation Forces? Why did so many die or were they shot?

The answer has finally been found in the military archives in South Africa.

In a telegram sent on 15 May 1916 from the Ministry of Defence (Johannesburg) to the House of Parliament (Pretoria) the following information was given: Sixteen hundred and ninety five (1695) horses and nine hundred and forty four (944) mules were destroyed near Swakopmund in November / December 1915 on account of a glanders (horse disease) outbreak which occurred amongst South African Union Defence Force animals that had been moved down to the coast in October. Immediately all possible steps were taken to deal with the glanders and to eradicate the disease. On receiving notification of the glanders outbreak in Namibia a veterinary officer with a supply of mallein (a fluid used in the diagnosis of glanders, when injected into an animal infected with glanders mallein causes a sharp rise of temperature) was dispatched from Cape Town on SS ”British Prince”.

Unfortunately the ship was wrecked on its way and the officer’s arrival in Swakopmund was delayed by 10 days. Animals showing critical symptoms were immediately destroyed by the veterinary officer.

The remainder was tested with mallein and those that reacted positively were also destroyed to prevent the spreading of infection.

”Glanders” is a chronic, usually fatal bacterial disease which is highly infectious among horses caused by ”Pseudomonas mallei”. The main symptoms are severe coughing, pneumonia, a nasal discharge and swollen lymph nodes.

The disease occurs more often among poorly fed, weak horses or those kept under crowded or unhygienic conditions. The glanders is one of the oldest diseases known and can also be fatal to humans. No glanders vaccine has been discovered yet.

The control can be exercised only by destruction of infected animals.

The conclusion is that the skeletons were most likely not German Schutztruppe horses. At no period in time there were so many German horses located at Swakopmund or at the coast and the few German soldiers had left Swakopmund early in 1915 with all their horses. Another fact to rule out German origin of the skeletons is that the horses that were buried in the dunes were destroyed approximately 5 months after the German South West Africa campaign had ended by the peace treaty in Khorab on 9 July 1915.

The telegram from the Ministry of Defence to the House of Parliament, sent on 15 May 1916, confirms the fact that the destroyed horses were South African Defence Force horses. General Louis Botha (Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa and Commander-in-Chief of its armed forces) was questioned in parliament on this issue on May 17, 1916.

Horse sickness as a cause of the mass destruction of horses can be ruled out because the disease does not occur at the Namibian coast. The transmitter of horse sickness, Theculicoides midge (an insect) can not survive at the coast.

Graves seem to disappear now and then for a few years and this is an interesting phenomenon itself. The shifting sand of dunes completely covers up the skeletons from time to time. It happens when one visits a known site that no trace of the horse bones can be found but later they are suddenly exposed again.

Railroad track dissapeared beneath the desert sands

Another thing that diappeared beneath the hifting desert sands was this old railroad track:

The “Little 5“ of the Namib

Sidewinder Snake (Bitis Perinqueyi)

This little endemic snake is one of the smallest adders in the world second after the namaqua dwarf adder. This adder reaches a length of 30cm and has eyes on top of the head, which allows the snake to burrow under the sand and still keep its eyes out surveying the surroundings for prey. They move in a lovely sidewinding fashion, which allows them to move along the slip face of dunes where the sand is loose. Sidewinding also keeps most of the body off the sand at any given moment and allows the snake to move over hot sand without overheating. They are front fanged and have a combination of Cytotoxic and Neurotoxic poison. They give live birth (viviparous) and have up to 10 young during the summer months. A little black point on the tail is used to attract lizards closer to the snake while it lies below the surface of the sand out of sight.

Caterpillar tracks or Side Winder Snakes?

Yes, both are common to the Perinqueys adder commonly known as a Sidewinder, which leaves caterpillar-like tracks on the slip face of dunes. When followed these tracks normally lead to the point where it buries itself under the sand waiting for a lizard to eat.

Namaqua Chameleon (Chamaeleo namaquensis)

Found in the western parts of Namibia and the North West of South Africa. This is a large short tailed chameleon that spends most of its life on the ground hunting for insects. They reach a length of up to 30cm and are one of the fasted moving chameleons in the world relative to other chameleons. Their basic color is black but color can change according to mood and willful decisions. Normally dark colored in the morning to attract the sun, once warm the chameleon can move faster and hunt more efficiently. When it’s too hot it turns lighter to reflect the sun. When angry it is black and when nervous it is black. They can see in both directions at the same time, 180 degrees on each eye independently. They need both eyes on the prey when catching it with their long tongue, which can reach the entire length of the body including the tail.

They lay eggs about twice a year that take about 4 months to hatch.

Chameleons, of which 19 species occur in

Southern Africa and 162 species worldwide,

change colour by willful decision, it’s not only according to the natural background colour

but the mood the animal is in.

e.g. Chameleons turn black when it’s cold to absorb the sun and white when it’s hot to reflect the sun.

Tractrac chat (Cercomela tractrac)

The tractrac chat is a small passerine bird of the Old World flycatcher family Muscicapidae. It is a common resident breeder in southernmost Angola, western Namibia and western South Africa.

Its habitat is Karoo and desert scrub, hummock dunes and gravel plains.

Description

The tractrac chat is 14–15 cm long with a weight of 20 g. Its tail is white with a dark inverted “T” at the tip, reminiscent of the pattern shown by several wheatears. The short straight bill and the legs and feet are black. It has a dark eye. The Namib form found on hummock dunes and at the coast has almost white plumage with grey wings and grey tail marking. The south-eastern form, found in gravel plains has brown upperparts with blackish flight feathers and tail markings. Its underparts are white. The sexes are similar, but the juvenile is more mottled than the adult.

This species is smaller than the Karoo chat which also has the white of the outer tail feathers extending to the tip. It is paler and greyer than Familiar and sickle-winged chats, both of which have a darker rump.

The tractrac chat has a soft fast “tactac” song and a loud chattering territorial defence call.

Behaviour

The tractrac chat builds a cup-shaped nest of straw and leaves on the ground, usually under a bush or shrub. It lays two to three red eggs. This species is monogamous, mating for life.

It is usually seen singly or in pairs. It forages from the ground for insects including butterflies, bees, wasps, locusts and ants. Prey is typically taking in a short flight.

Conservation status

This common species has a large range, with an estimated extent of 1,000,000 km². The population size is believed to be large, and the species is not believed to approach the thresholds for the population decline criterion of the IUCN Red List (i.e. declining more than 30% in ten years or three generations). For these reasons, the species is evaluated as Least Concern.[1]

Namib Dune Gecko (Pachydactylus rangei)

This endemic gecko is also known as the Palmato gecko or Web Footed gecko and can be found throughout the Namib Desert especially on the compacted wind side of the dunes. They are nocturnal and have large fixed lens eyes without eyelids, which they keep clean by licking with long tongues.

Web feet act as Sand shoes, the equivalent of snow shoes. They come in a variety of colors and patterns with an almost transparent skin which has visible blood vessels beneath the skin. They collect their water needs from what they eat, a diet consisting of various insects such as crickets, beetles, termites, beetle larvae and crickets. In times of need they can be seen allowing fog to condense on their large eyes and licking the drops of water off with their long tongues.

Geckos are mostly nocturnal

with 111 species found in Southern Africa

and 1130 species described worldwide.

The Namib dune gecko is unique due to the fact that it is the only fully web footed gecko

in Southern Africa.