3. Slovakia: High and Low Tatra Mountains (Low Tatras National Park) – 1996

In the morning at 4.00 o’clock The Wandelgek reached the desolate Liptovski Mikulas.

Liptovsky Mikulas

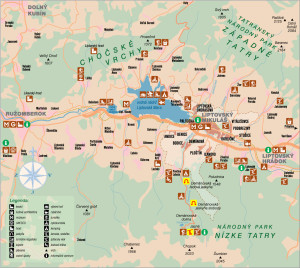

Liptovsky Mikulas (formerly Liptovsky Svaty Mikulas, German: Liptau-St Nicholas or St. Nikolaus in der Liptau, Hungarian: Liptószentmiklos), is a city in northern Slovakia with more than 33,000 inhabitants. Liptovsky Mikulas is located in the Liptov region between the High and the Low Tatras and the river Vah. In the northwest borders the town to the Chočský hills.

History

The place Mikuláš was first mentioned in 1286. The first written reference to St. Nicholas Church dates from 1299. The church, which was the beginning of a larger settlement, is the oldest building of Liptovsky Mikulas.

Mikuláš was an important center of crafts in the Liptov region. The craftsmen formed guilds as blacksmith, furrier, tailor, hatter and butcher. The oldest guild, named in 1508 was that of a shoemaker.

Liptovsky Mikulas in 1677 became the seat of the local district and the county Liptov. The legendary Slovak “Robin Hood”, Juraj Jánošík, here was convicted in 1713 and executed. In the nineteenth century the city became one of the centers of the Slovak national movement.

From 1919 carried the place, as previously was the case, the official Slovak name Liptovsky Svaty Mikulas. In 1952 the word was Svaty (Dutch: holy) removed from the name. In the twentieth century many villages were incorporated Liptovsky Mikulas.

After three hours of waiting left there on a bus to the campsite at Mare Liptovski, situated on the shore of a lake. However he didn’t like the campsite and thus returned to Liptovsky Mikolas. Up in the mountains was a campsite (Kemping Bystrina), surrounded by forest at the village of Demanskovy Dolina. Somewhere The Wandelgek must have taken a wrong turn and when searching for the right route he met a Polish guy wearing pitch black sunglasses who directed him towards the camp site. He reached a bus stop and took the bus to the campsite.

Demanovska Dolina

Demänovská Dolina (Hungarian: Göncölfalva) is a Slovak town in the Žilina region, and is part of the district Liptovsky Mikulas. Demänovská Dolina counts 203 inhabitants.

It was now 13.00pm and time to explore the area. The Wandelgek decided to visit the nearby ice cave and walked over there.

After a tough climb up a steep cliff, he reached the entrance where he met a young Dutch couple from Alphen aan den Rijn. Like The Wandelgek, the girl had been to Hungary as a choir member and not just to Budapest but also to Tokaj. Feast of recognition. We compared Slovakia and Hungary and there were plenty of similarities (Budapest & Prague / Closet paper that you need to ask for before you go to the toilet and not lockable toilet doors in public places). Furthermore, the conversation turned to Romania and Bucharest, Auschwitz, Prague, the Tatras and more. Their impression of Slovakia was that the country was well on its way to become a populat tourist country.

Low Tatras National Park

The Low Tatras National Park (Slovak: Národný park Low Tatras) with 728 km² the largest national park in Slovakia. Along with a buffer zone of 1102 km² includes the whole Low Tatras, the mountains between the Váh and the Hron.

In sparsely populated, but easily accessible area there are several caves, including the Freedom of Demänova Cave, a cave discovered in 1921, and the ice of Demänova that since the Middle Ages is known. Freedom Cave is the most visited cave in Slovakia: the 8126 meters there are 1800 accessible. The caves form a national natural (Národná prírodná pamiatka), one of five in the park. Ten areas have the status of a national nature reserve (Národná prírodná rezervácia), including the Ďumbier, the highest mountain in the Low Tatras.

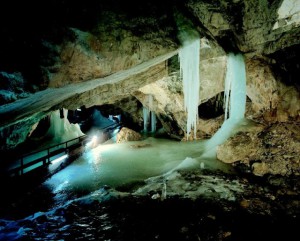

The ice cave

The ice was cold, deep and very beautiful. In the jagged limestone forms on the ceiling, using some imagination, you could see animal and human heads. The guide used a cassette player (it’s 1996 ;-)) with music and a german narration, so much information was understandable.

Demänovská Ice Cave or Demänovská ľadová jaskyňa (in Slovak) is an ice cave in the Demänovská Valley (Low Tatra) in Slovakia. It was first mentioned in 1299 and is one of oldest known caves in Europe. After the opening of Demänovská jaskyňa Slobody in 1924, interest in this cave declined. It was reopened to the public after the reconstruction of wooden stairs and electrical lighting in 1952, with 680 m accessible out of the 1,975 m. Currently, the route for visitors is 850 m long and takes about 45 minutes to traverse.

Natural settings

The Demänovská Ice Cave was formed in Middle Triassic dark-grey Guttenstein limestones of the Krížna Nappe, along tectonic faults by the previous ponor flow of the Demänovka River, which flowed from the Demänovská Cave of Peace. It presents the northern previously spring part of the Demänovský cave system. Some upper parts of the cave are formed by waters of side ponor branch of Demänovka River, which penetrated from the adjacent Dvere Cave and from the New Cave in Bašta.

The length of measured spaces is 2,445 m with vertical distance of 57 m. The cave spaces of three developmental levels consist of oval, river modelled passages with ceiling and side channels (Black Gallery, Lake Pasage, Bear’s Passage) and domes reshaped by collapses and frost weathering (Gravel Dome, Great Dome, Kmeť’s Dome, Bel’s Dome, Halaš’ Dome, Dome of Ruins). The passages descend from the entrance to the depth of 40 to 50 m.

Ice fill occurs in the lower parts of the cave, mainly in the Kmeť’s Dome. There is floor ice, ice columns, stalactites and stalagmites. The conditions for glaciation started after burying several openings to the surface in consequence of slope modeling processes, by which the air replacement was restricted. Heavier cold air is kept in the lower parts of the cave. Seeping precipitation water freezes in overcooled underground spaces. Air temperature in glaciated parts fluctuates around 0 °C and in direction to the back non-glaciated parts rises from 1.3 up to 5.7 °C. Relative air humidity is between 92 and 98 %.

Original flowstone fill was preserved in several places of the cave (stalactites, stalagmites, sinter covers on the walls, floor crusts and other forms), which is, however, considerably destroyed by frost weathering in the glaciated part of the cave. Sinter formations are coloured on the surface into gray up to black from soot of tar torches, oil burners and paraffin lamps, which were used for lighting until 1924. This phenomenon, in the case of the Demänovská Ice Cave, can be considered more or less a cultural one, connected with its rich history.

The cave belongs among long known finding places of bones of various vertebrates including the cave bear (Ursus spelaeus), which were in the first half of the 18th century considered dragons’ bones. That’s why the cave was called Dragon’s Cave in the past. By now, eight bat species were found in its underground spaces. It represents the most important wintering place of the Northern Bat (Eptesicus nilssonii) and the second most important one of the Whiskered/Brandt’s Bat (Myotis mystacinus/Myotis brandtii) in Slovakia. Species representation of tiny cave fauna – invertebrates is substantially smaller in glaciated parts as compared with non-glaciated ones.

History

It is passed on that the Demänovská Ice Cave is known from time immemorial. The first mention about the openings to caves in the Demänovská Valley is recorded in the Esztergom Chapter document from 1299. However, it cannot be related to a specific cave. The first written mention about the Demänovská Ice Cave is related to the description of a cave not far from Liptovský Mikuláš and comes from 1672 by J. P. Hain who was interested in cave bear bones and took them for dragon’s bones.

Further mentions of the Demänovská Ice Cave are connected with G. Buchholtz jr., who surveyed its spaces in 1719. He sent the description together with a sketch of the cave to M. Bel, who published them in 1723.

Emperor’s commission, which were surveying Tatras and adjacent mountains overlooked the cave in 1751. Plenty inscriptions on cave walls and preserved rich literature show a great interest of then scientific circles and general public in the cave. There are also signatures of important persons of the Slovak history on its walls (M. M. Hodža, S. Chalupka, G. Fejérpataky-Belopotocký and others).

The primary opening the cave for public took place around the half of the 19th century, though an adaptation of its spaces to make descend easier mainly in the steep and iced entrance part was done earlier thanks to the Demänová Association of Owners (composesorate). Further adjustments in the cave were carried out by the Liptov’s Section of the Ugrian Carpathian Club, which built the first hostel under the cave in 1885 and began to take care of the development of tourism in the Demänovská Valley. A. Žuffa jr. discovered the Dome of Ruins in the lower part of the cave in 1909. The interest in the Demänovská Ice Cave was gradually falling down after opening the Demänovská Cave of Liberty for the public in 1924. A. Král together with V. Benický, discovered the upper dripstone parts of the cave in 1926.

The cave was reopened in 1950 – 1952, including installation of electric lighting. S. Šrol, P. Revaj and P. Droppa discovered the Demänovská Cave of Peace from the Lake Passage in January 1952. This had disturbed the temperature regime in the cave, so in 1953 – 1954 measures were taken to restore the ice fill (closing the dug opening in the Dome of Ruins, building a wall to divide parts with and without ice etc.). The show path was reconstructed through the years 1974 – 1976 and Gravel Dome was opened for the public. The cavers of the Demänovská Valley local group – a unit of the Slovak Speleological Society discovered the spaces above the Kmeť’s Dome in 1983. The cave has 650 m open for public with elevation difference of -48 m.

More information: http://www.ssj.sk/en/jaskyna/5-demanovska-ice-cave

and http://www.ssj.sk/en/jaskyna/4-demanovska-cave-of-liberty

After visiting the ice cave, The Wandelgek got a lift to the campsite where he slept before the tent in the sun. After about an hour The Wandelgek woke from thick raindrops falling and he crawled into the tent. Near the campsite was the Jagdrestaurant where dinner was served and at the end of afternoon The Wandelgek climbed to the top of a hill near the campsite to enjoy the beautiful views over the High and Low Tatras. By the time the sun went down, The Wandelgek descended quickly to the campsite.

The next morning it rained and the air was super gray and to make matters worse he learned that this would last several days. It seemed that the weather gods decided that walking in the Tatras was not to be, so The Wandelgek yielded and decided to visit the Czech capital of Prague. Bad weather in a city is less annoying than bad weather in mountains.

Two days later, after a sunny inbetween day that was perfect to finally go walking in the Low Tatras (see other blog), it rained again, and the air was super gray and to make matters worse, there was again a multi-day period of rain announced in the weather forecasts. It seemed that the weather gods decided that walking in the Tatra there for the Wandelgek no longer could sit, so he decided to give up and go to the Czech capital Prague. Bad weather in a city is in any case portable.

The Wandelgek wanted to visit another beautiful cave. That was the Cave of Liberty, a beautiful cave with the largest and most beautiful limestone waterfall of the area (and there were a lot of caves here). The cave consisted of long narrow corridors full of stalactites and stalagmites interspersed with large and high grottos. During the trip through the caves , The Wandelgek met an Australian guy who was on a three-month bicycle tour from Italy through Eastern Europe to Krakow in Poland.

Cave of Liberty

The Demänovská Cave of Liberty is located in the northern part of the Low Tatras in Liptov region within Demänovská Valley. It is the most visited cave in Slovakia.

Demänovská Cave of Liberty (Slovak: Demänovská jaskyňa Slobody) is a karst cave in Low Tatras in Slovakia. Discovered in 1921 and opened to the public in 1924, it is the most visited cave in Slovakia.

The public entrance is at an altitude of 870 metres (2,850 ft). Of the total length of 8,126 metres (5.0 mi), 1,800 metres (1.1 mi) are open to the public.

Cave bear bones were found in a passage now named Bear’s Passage (Slovak: Medvedia chodba).

Large domes have been created with the largest being the Great Dome, which is 41m high, with a length of 75m and width of 35m.

The path with educational boards in length of 400 m leads to the entrance of the cave in the elevation height 870 m. The duration of the walk is about 10-15 min. Average temperature in the cave is 6,1 – 7°C.

You can choose between traditional and long visit tour. But be careful because the long visit tour is held only once a day.

Traditional tour

It is 1.150 m long, the camber is 86 m and you climb altogether 913 stairs.

During the visit you can admire unique sinter forms created by underground flow of the river Demänovka, little karst lakes together with rich stalactite and stalagmite decorations and you will be informed about whole history of this remarkable cave.

Long tour

The long tour has length of 2.150 m and you have to climb 1.118 stairs.

Traditional visit is enriched by “the Big Dome” – the biggest underground space accessible for public with underground river bed and soft dead-white sinter, then “the Pink Hall“and “the King’s Gallery“, which has the most various decorations in the cave with unique cave water lilies and lake sponge shapes, cave pearls and plenty of other forms of sinter decoration.

The Wandelgek chose the long tour.

The national nature monument of the Demänovské Caves on the northern side of the Low Tatras Mts. is the longest cave system in Slovakia. The Demänovská Cave of Liberty belongs among its dominating caves. It has been captivating the visitors by its rich flowstone fill of various colours, magical flow of underground Demänovka as well as the charming pools for many years. It is the most visited show cave in Slovakia.

The cave represents morphologically the most varied part of the Demänovský Cave System. It is formed in the Middle Triassic dark-gray Gutenstein limestones of the Krížna Nappe along the tectonic faults by the ancient ponor flow of Demänovka and its side hanging ponor tributaries. The length is 8,497 m with elevation distance of 120 m.

The lower oval, river modeled passages of the cave represent four horizontal development levels (Marble Riverbed, Loamy Passage, Dry Passage, Ground Floor, Král’s Gallery). They are in places widened by collapses (Great and Spouting Dome, Pink Hall, Hell Dome). Steeply descending passages lead into cave levels in hanging positions, mostly from the place of present cave entrance and exit. Except for the smaller oval passages (Passage of Suffering, Virgin Passage, Bear’s Passage, Treasury) they include also bigger spaces (Sphere Dome, Parachute Abyss, Janosik’s Dome, Hviezdoslav’s Dome, Deep Dome). The Miraculous Halls, Magical Passage and Stone Vineyard have a fissure character. From among the flowstone fills, the water lilies and other lacustrine forms (sponge, coral, grapes forms) and also eccentric stalactites are unique. Mighty flowstone waterfalls and columns, sphaerolitic stalactites and many other forms of stalactites and stalagmites are captivating. A thick layer of white soft sinter – moonmilk can be found in the Great Dome.

The underground water course of Demänovka, which springs in the non-karst territory under the main ridge of the Low Tatras, flows through the cave. It sinks underground in Lúčky and springs again through the Vyvieranie Cave northerly from the Demänovská Cave of Liberty. The Great Lake is 52 m long, 5 to 12 m wide and more than 7 m deep. Air temperature is from 6,1 to 7,0 °C, relative humidity 94 to 99 %.

The bones of cave bear (Ursus spelaeus) were found in the Bear’s Passage (Medvedia chodba). The finding of the palpigrade Eukoenenia spelaea means one of the most northern occurrences of this arachnids in the world, which ranks the cave among the biospeleological localities of European importance. From among the tiny invertebrates, mostly the multipede Allorhiscosoma sphinx (endemite of the middle Slovakian caves) and amphipods Synurella intermedia a Niphargus tatrensis are important.

History

The cave was discovered by A. Král with the help of A. Mišura and other surveyors through the dry lowest ponor of Demänovka River in 1921. The Commission for Publicizing of the Demänovské Caves was established in 1922 and began the development works for opening for the public. An interim electrical lighting was installed in 1923. A part of the cave, leading from the entrance gallery through the Marble Riverbed and Great Dome up to the Golden Lake, was opened for the public in 1924.

An underground water lake, full of the water that creates these formations of stalagtites and stalagmites …

The Cooperative of the Demänovské Caves originated in 1925 and continued in the work of the Commission. An expedition headed by A. Král discovered in 1926 the Jánošík’s Dome, Virgin Passage, Passage of Suffering and the Red Gallery. V. Benický and A. Lutonský discovered the Magical Passage and Violet Dome in 1927, Svantovít’s Halls in 1929, and one year later the Miraculous Halls. A new entrance to the cave was dug out in 1928 in the Točište Valley, which was opened to public in 1930. A new permanent electric lighting was installed in 1931 and the show path was prolonged as far as the Pink Hall with a fork into the Hviezdoslav’s Dome. The same year J. Zelinka discovered the Bear’s Passage and found out its communication with the surface. A new exit from the cave was dug out in 1933 from the Bear’s Passage, which changed the show path.

The upper parts of the Hviezdoslav’s Dome were opened to public in 1931 – 1933. During 1948 – 1955 were the caves of the Demänovská Valley surveyed and measured by A. Droppa. Under his leadership in 1951 the Demänovská Cave of Liberty was connected with the Pustá Cave, and in 1983 the speleodivers V. Žikeš and Ľ. Kokavec found its connection with the Vyvieranie Cave. Several unsuccessful attempts in 1952, 1968, 1974 and 1983 were altered with a successful one on the turn of 1986 and 1987 when its natural connection with the Demänovská Cave of Peace was reached. The cavers from the group of the Demänovská Valley found its connection with the Cave Under the Cliff and Valley Cave in 1989, and the connection with the Cave of Ruins in 1992.

After having visited the cave, The Wandelgek went to Liptovsky Mikulas to the railway station and bought train tickets to Prague. That train was leaving the next morning.

Somewhere in central Liptovsky Mikulas he found a bakry and ate some pastry and then he walked through down town Liptovsky Mikulas and saw its little church.

The Wandelgek walked to nearby Liptovsky Izba, an authentic Slovakian restaurant in mountain lodge-style, where he ordered a Slovak skewer using the menu and his slovakian phrasebook. This restaurant is an absosolute must see and must taste location for this little town.

Then he went back to the campsite to sleep early. Tomorrow is another long travel day.

The Wandelgek packed his tent and visited the campsite canteen for an early breakfast. There he met the Berlin hikers again whom he had met earlier on the Chopok and Australian guy he had met in the cave. The Berlin people were in a festive mood because the night before Germany won the European soccer championship. Moreover, that was in a 2-1 final against the Czech Republic.

The Wandelgek then left to the station of Liptovsky Mikulas and took the train to Prague. It had been raining almost continuously or the last 2 days and today it rained…

Conclusion:

The area around Liptovsky Mikulas is absolutely gorgeous and the town itself is quit nice if it weren’t such dreary weather. The Wandelgek really wanted to make some mountain hikes across the ridges of the Low Tatras but that’s no fun with continuous rain every day again.

But the one day of sunny weather at Mount Chopok was gorgeous and the caves of the Tatras are magnificent.