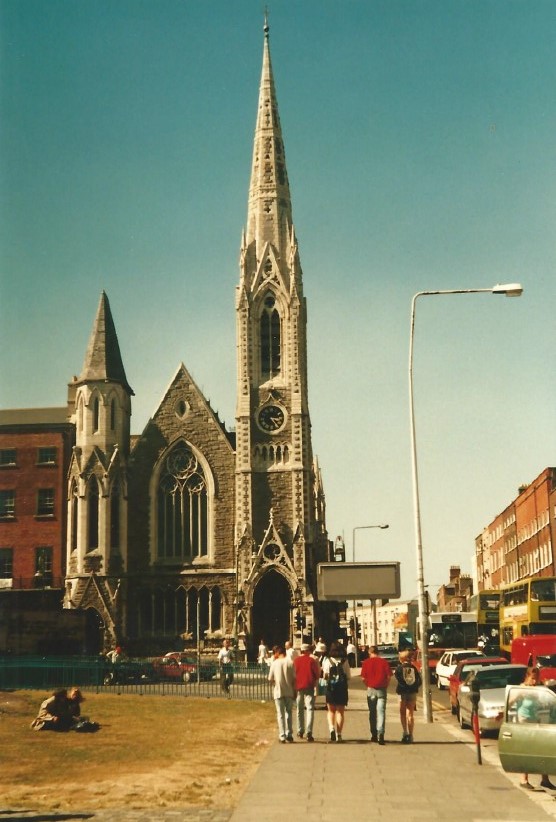

5. Dublin and surroundings

From Clifden in the Connemara The Wandelgek traveled by bus to Galway and then by train to Dublin. On the outskirts of Dublin in a wooded area, he set up his tent at a campsite (Shankill), which was easily accessible by subway.

Dublin

Dublin (/ˈdʌblɨn/; Irish: Baile Átha Cliath, pronounced [blʲaˈklʲiə]) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. Dublin is in the province of Leinster on Ireland’s east coast, at the mouth of the River Liffey.

Founded as a Viking settlement, the Kingdom of Dublin became Ireland’s principal city following the Norman invasion. The city expanded rapidly from the 17th century and was briefly the second largest city in the British Empire before the Act of Union in 1800. Following the partition of Ireland in 1922, Dublin became the capital of the Irish Free State and later the Republic of Ireland.

Dublin is administered by a City Council. The city is listed by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network (GaWC) as a global city, with a ranking of “Alpha-“, placing it among the top thirty cities in the world. It is a historical and contemporary centre for education, the arts, administration, economy and industry.

History

Toponymy

Although the area of Dublin Bay has been inhabited by humans since prehistoric times, the writings of Ptolemy (the Greco-Roman astronomer and cartographer) in about 140 AD provide possibly the earliest reference to a settlement there. He called the settlement Eblana Civitas.

The name Dublin comes from the Irish name Dubhlinn or Duibhlinn, meaning “black pool”. This is made up of the elements dubh (black) and linn (pool). In most Irish dialects, dubh is pronounced [ˈd̪ˠʊvˠ]. The original pronunciation is preserved in the names for the city in other languages such as Old English Difelin, Old Norse Dyflin, modern Icelandic Dyflinn and modern Manx Divlyn. Other localities in Ireland also bear the name Duibhlinn, variously anglicized as Devlin, Divlin and Difflin. Historically, scribes using the Gaelic script wrote bh with a dot over the b, rendering Duḃlinn or Duiḃlinn. Those without knowledge of Irish omitted the dot, spelling the name as Dublin.

Baile Átha Cliath, meaning “town of the hurdled ford”, is the common name for the city in modern Irish. Áth Cliath is a place name referring to a fording point of the River Liffey near Father Mathew Bridge. Baile Átha Cliath was an early Christian monastery, believed to have been in the area of Aungier Street, currently occupied by Whitefriar Street Carmelite Church.

The subsequent Scandinavian settlement centred on the River Poddle, a tributary of the Liffey in an area now known as Wood Quay. The Dubhlinn was a small lake used to moor ships; the Poddle connected the lake with the Liffey. This lake was covered during the early 18th century as the city grew. The Dubhlinn lay where the Castle Garden is now located, opposite the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin Castle. Táin Bó Cuailgne (“The Cattle Raid of Cooley”) refers to Dublind rissa ratter Áth Cliath, meaning “Dublin, which is called Ath Cliath”.

Middle Ages

Dublin was established as a Viking settlement in the 9th century and, despite a number of rebellions by the native Irish, it remained largely under Viking control until the Norman invasion of Ireland was launched from Wales in 1169. The King of Leinster, Diarmait Mac Murchada, enlisted the help of Strongbow, the Earl of Pembroke, to conquer Dublin. Following Mac Murrough’s death, Strongbow declared himself King of Leinster after gaining control of the city. In response to Strongbow’s successful invasion, King Henry II of England reaffirmed his sovereignty by mounting a larger invasion in 1171 and pronounced himself Lord of Ireland. Around this time, the county of the City of Dublin was established along with certain liberties adjacent to the city proper. This continued down to 1840 when the barony of Dublin City was separated from the barony of Dublin. Since 2001, both baronies have been redesignated the City of Dublin.

Dublin Castle, which became the centre of Norman power in Ireland, was founded in 1204 as a major defensive work on the orders of King John of England. Following the appointment of the first Lord Mayor of Dublin in 1229, the city expanded and had a population of 8,000 by the end of the 13th century. Dublin prospered as a trade centre, despite an attempt by King Robert I of Scotland to capture the city in 1317. It remained a relatively small walled medieval town during the 14th century and was under constant threat from the surrounding native clans. In 1348, the Black Death, a lethal plague which had ravaged Europe, took hold in Dublin and killed thousands over the following decade.

Dublin was incorporated into the English Crown as the Pale, which was a narrow strip of English settlement along the eastern seaboard. The Tudor conquest of Ireland in the 16th century spelt a new era for Dublin, with the city enjoying a renewed prominence as the centre of administrative rule in Ireland. Determined to make Dublin a Protestant city, Queen Elizabeth I of England established Trinity College in 1592 as a solely Protestant university and ordered that the Catholic St. Patrick’s and Christ Church cathedrals be converted to Protestant.

The city had a population of 21,000 in 1640 before a plague in 1649–51 wiped out almost half of the city’s inhabitants. However, the city prospered again soon after as a result of the wool and linen trade with England, reaching a population of over 50,000 in 1700.

Early modern

As the city continued to prosper during the 18th century, Georgian Dublin became, for a short period, the second largest city of the British Empire and the fifth largest city in Europe, with the population exceeding 130,000. The vast majority of Dublin’s most notable architecture dates from this period, such as the Four Courts and the Custom House. Temple Bar and Grafton Street are two of the few remaining areas that were not affected by the wave of Georgian reconstruction and maintained their medieval character.

Dublin grew even more dramatically during the 18th century, with the construction of many famous districts and buildings, such as Merrion Square, Parliament House and the Royal Exchange. The Wide Streets Commission was established in 1757 at the request of Dublin Corporation to govern architectural standards on the layout of streets, bridges and buildings. In 1759, the founding of the Guinness brewery resulted in a considerable economic gain for the city. For much of the time since its foundation, the brewery was Dublin’s largest employer.

Late modern and contemporary

Dublin suffered a period of political and economic decline during the 19th century following the Act of Union of 1800, under which the seat of government was transferred to the Westminster Parliament in London. The city played no major role in the Industrial Revolution, but remained the centre of administration and a transport hub for most of the island. Ireland had no significant sources of coal, the fuel of the time, and Dublin was not a centre of ship manufacturing, the other main driver of industrial development in Britain and Ireland. Belfast developed faster than Dublin during this period on a mixture of international trade, factory-based linen cloth production and shipbuilding.

The Easter Rising of 1916, the Irish War of Independence, and the subsequent Irish Civil War resulted in a significant amount of physical destruction in central Dublin. The Government of the Irish Free State rebuilt the city centre and located the new parliament, the Oireachtas, in Leinster House. Since the beginning of Norman rule in the 12th century, the city has functioned as the capital in varying geopolitical entities: Lordship of Ireland (1171–1541), Kingdom of Ireland (1541–1800), island as part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1801–1922), and the Irish Republic (1919–1922). Following the partition of Ireland in 1922, it became the capital of the Irish Free State (1922–1949) and now is the capital of the Republic of Ireland. One of the memorials to commemorate that time is the Garden of Remembrance.

Since 1997, the landscape of Dublin has changed immensely. The city was at the forefront of Ireland’s rapid economic expansion during the Celtic Tiger period, with enormous private sector and state development of housing, transport and business.

Government

Local

From 1842, the boundaries of the city were comprehended by the baronies of Dublin City and the Barony of Dublin. In 1930, the boundaries were extended by the Local Government (Dublin) Act. Later, in 1953, the boundaries were again extended by the Local Government Provisional Order Confirmation Act.

Dublin City Council is a unicameral assembly of 63 members elected every five years from Local Election Areas. It is presided over by the Lord Mayor, who is elected for a yearly term and resides in Mansion House. Council meetings occur at Dublin City Hall, while most of its administrative activities are based in the Civic Offices on Wood Quay. The party or coalition of parties, with the majority of seats adjudicates committee members, introduces policies, and appoints the Lord Mayor. The Council passes an annual budget for spending on areas such as housing, traffic management, refuse, drainage, and planning. The Dublin City Manager is responsible for implementing City Council decisions.

National

As the capital city, Dublin seats the national parliament of Ireland, the Oireachtas. It is composed of the President of Ireland, Seanad Éireann as the upper house, and Dáil Éireann as the lower house. The President resides in Áras an Uachtaráin in the Phoenix Park, while both houses of the Oireachtas meet in Leinster House, a former ducal palace on Kildare Street. It has been the home of the Irish parliament since the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922. The old Irish Houses of Parliament of the Kingdom of Ireland were located in College Green.

Government Buildings house the Department of the Taoiseach, the Council Chamber, the Department of Finance and the Office of the Attorney General. It consists of a main building (completed 1911) with two wings (completed 1921). It was designed by Thomas Manley Dean and Sir Aston Webb as the Royal College of Science. The First Dáil originally met in the Mansion House in 1919. The Irish Free State government took over the two wings of the building to serve as a temporary home for some ministries, while the central building became the College of Technology until 1989. Although both it and Leinster House were intended to be temporary, they became the permanent homes of parliament from then on.

For elections to Dáil Éireann the city is divided into five constituencies: Dublin Central (3 seats), Dublin Bay North (5 seats), Dublin North–West (3 seats), Dublin South–Central (4 seats) and Dublin Bay South (4 seats). Nineteen TD’s are elected in total.

Politics

In the past Dublin city was regarded as a stronghold for Fianna Fáil, however following the Irish local elections, 2004 the party was eclipsed by the centre-left Labour Party. In the 2011 general election the Dublin Region elected 18 Labour Party, 17 Fine Gael, 4 Sinn Féin,2 Socialist Party, 2 People Before Profit Alliance and 3 Independent TDs. Fianna Fáil lost all but one of its sitting TDs in the region.

Geography

Landscape

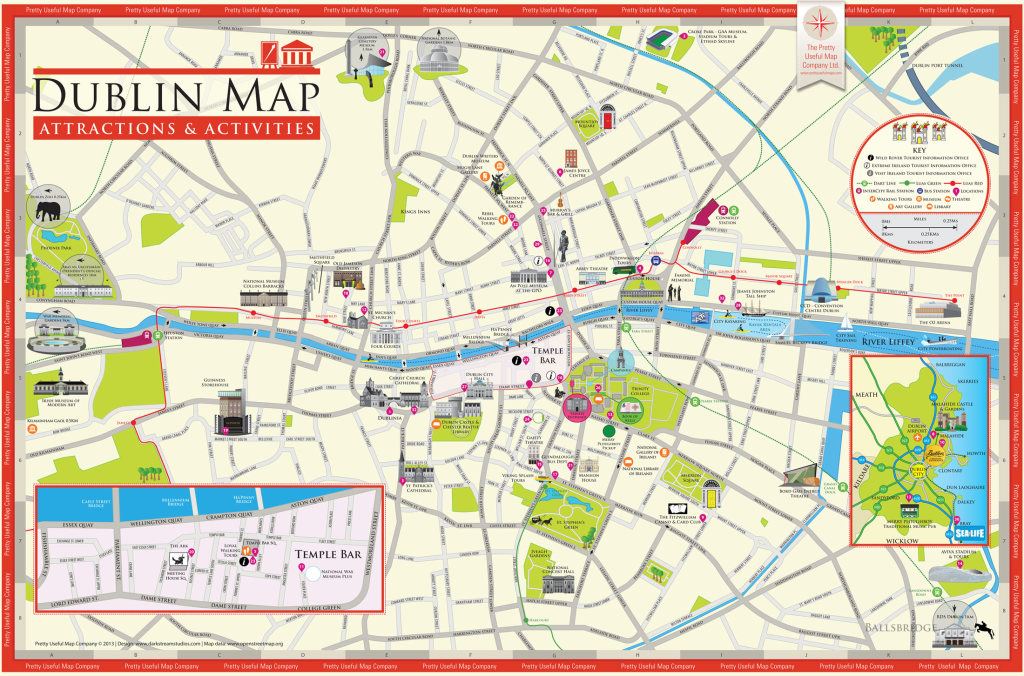

Dublin is situated at the mouth of the River Liffey and encompasses a land area of approximately 115 km2. It is bordered by a low mountain range to the south and surrounded by flat farmland to the north and west. The Liffey divides the city in two between the Northside and the Southside. Each of these is further divided by two lesser rivers – the River Tolka running northwest from Dubin Bay, and the River Dodder running southwest from the mouth of the Liffey. Two further water bodies – the Grand Canal on the southside and the Royal Canal on the northside – ring the inner city on their way to the west and the River Shannon.

The River Liffey bends at Leixlip from a predominantly east-west direction to a southwesterly route, and this point also marks the change from urban development to more agricultural land usage.

Cultural divide

A north-south division has traditionally existed, with the River Liffey as the divider. The Northside is generally seen as working class, while the Southside is seen as middle to upper-middle class. The divide is punctuated by examples of Dublin “sub-culture” stereotypes, with upper-middle class constituents seen as tending towards an accent and demeanour synonymous with the Southside, and working-class Dubliners seen as tending towards characteristics associated with Northside and inner-city areas. Dublin’s economic divide is east-west as well as north-south. There are also social divisions evident between the coastal suburbs in the east of the city, including those on the Northside, and the newer developments further to the west.

Places of interest

Landmarks

Dublin has many landmarks and monuments dating back hundreds of years. One of the oldest is Dublin Castle, which was first founded as a major defensive work on the orders of King John of England in 1204, shortly after the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169, when it was commanded that a castle be built with strong walls and good ditches for the defence of the city, the administration of justice, and the protection of the King’s treasure. Largely complete by 1230, the castle was of typical Norman courtyard design, with a central square without a keep, bounded on all sides by tall defensive walls and protected at each corner by a circular tower. Sited to the south-east of Norman Dublin, the castle formed one corner of the outer perimeter of the city, using the River Poddle as a natural means of defence.

One of Dublin’s newest monuments is the Spire of Dublin, or officially titled “Monument of Light”. It is a 121.2 metres (398 ft) conical spire made of stainless steel and is located on O’Connell Street. It replaces Nelson’s Pillar and is intended to mark Dublin’s place in the 21st century. The spire was designed by Ian Ritchie Architects, who sought an “Elegant and dynamic simplicity bridging art and technology”. During the day it maintains its steel look, but at dusk the monument appears to merge into the sky. The base of the monument is lit and the top is illuminated to provide a beacon in the night sky across the city.

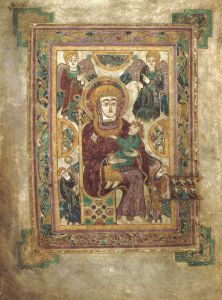

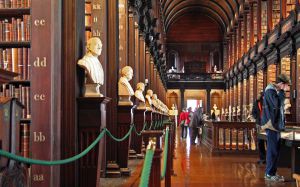

Many people visit Trinity College, Dublin to see the Book of Kells in the library there. The Book of Kells is an illustrated manuscript created by Irish monks circa. 800 AD.

The Ha’penny Bridge; an old iron footbridge over the River Liffey is one of the most photographed sights in Dublin and is considered to be one of Dublin’s most iconic landmarks.

Other popular landmarks and monuments include the Mansion House, the Anna Livia monument, the Molly Malone statue, Christ Church Cathedral, St Patrick’s Cathedral, Saint Francis Xavier Church on Upper Gardiner Street near Mountjoy Square, The Custom House, and Áras an Uachtaráin. The Poolbeg Towers are also iconic features of Dublin and are visible in many spots around the city.

Parks

Dublin has more green spaces per square kilometre than any other European capital city, with 97% of city residents living within 300 metres of a park area. The city council provides 2.96 hectares (7.3 acres) of public green space per 1,000 people and 255 playing fields. The council also plants approximately 5,000 trees annually and manages over 1,500 hectares (3,700 acres) of parks.

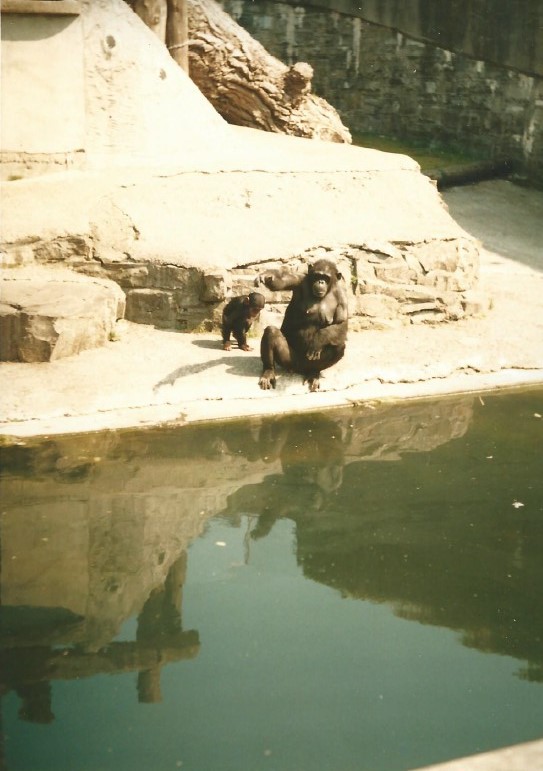

There are many park areas around the city, including the Phoenix Park, Herbert Park and St Stephen’s Green. The Phoenix Park is about 3 km (2 miles) west of the city centre, north of the River Liffey. Its 16 km (10 miles) perimeter wall encloses 707 hectares (1,750 acres) one of the largest walled city parks in Europe. It includes large areas of grassland and tree-lined avenues, and since the 17th century has been home to a herd of wild Fallow deer. The residence of the President of Ireland (Áras an Uachtaráin), which was built in 1751, is located in the park. The park is also home to Dublin Zoo, the official residence of the United States Ambassador, and Ashtown Castle. Music concerts have also been performed in the park by many singers and musicians.

St Stephen’s Green is adjacent to one of Dublin’s main shopping streets, Grafton Street, and to a shopping centre named for it, while on its surrounding streets are the offices of a number of public bodies and the city terminus of one of Dublin’s Luas tram lines. Saint Anne’s Park is a public park and recreational facility, shared between Raheny and Clontarf, both suburbs on the North Side of Dublin. The park, the second largest municipal park in Dublin, is part of a former 2 square kilometres (1 sq mi) (500 acre) estate assembled by members of the Guinness family, beginning with Benjamin Lee Guinness in 1835 (the largest municipal park is nearby (North) Bull Island, also shared between Clontarf and Raheny).

Demographics

The City of Dublin is the area administered by Dublin City Council, but the term “Dublin” normally refers to the contiguous urban area which includes parts of the adjacent local authority areas of Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown, Fingal and South Dublin. Together, the four areas form the traditional County Dublin. This area is sometimes known as the Dublin Region. The population of the administrative area controlled by the City Council was 525,383 in the 2011 census, while the population of the urban area was 1,110,627. The County Dublin population was 1,273,069 and that of the Greater Dublin Area 1,804,156. The area’s population is expanding rapidly, and it is estimated by the Central Statistics Office that it will reach 2.1 million by 2020.

Since the late 1990s, Dublin has experienced a significant level of net immigration, with the greatest numbers coming from the European Union, especially the United Kingdom, Poland and Lithuania. There is also a considerable number of immigrants from outside Europe, particularly from China and Nigeria. Dublin is home to a greater proportion of new arrivals than any other part of the country. Sixty percent of Ireland’s Asian population lives in Dublin. Over 15% of Dublin’s population was foreign-born in 2006.

Culture

The arts

Dublin has a world-famous literary history, having produced many prominent literary figures, including Nobel laureates William Butler Yeats, George Bernard Shaw and Samuel Beckett. Other influential writers and playwrights include Oscar Wilde, Jonathan Swift and the creator of Dracula, Bram Stoker. It is arguably most famous as the location of the greatest works of James Joyce, including Ulysses, which is set in Dublin and full of topical detail. Dubliners is a collection of short stories by Joyce about incidents and typical characters of the city during the early 20th century. Other renowned writers include J. M. Synge, Seán O’Casey, Brendan Behan, Maeve Binchy, and Roddy Doyle. Ireland’s biggest libraries and literary museums are found in Dublin, including the National Print Museum of Ireland and National Library of Ireland. In July 2010, Dublin was named as a UNESCO City of Literature, joining Edinburgh, Melbourne and Iowa City with the permanent title.

There are several theatres within the city centre, and various world famous actors have emerged from the Dublin theatrical scene, including Noel Purcell, Sir Michael Gambon, Brendan Gleeson, Stephen Rea, Colin Farrell, Colm Meaney and Gabriel Byrne. The best known theatres include the Gaiety, Abbey, Olympia, Gate, and Grand Canal. The Gaiety specialises in musical and operatic productions, and is popular for opening its doors after the evening theatre production to host a variety of live music, dancing, and films. The Abbey was founded in 1904 by a group that included Yeats with the aim of promoting indigenous literary talent. It went on to provide a breakthrough for some of the city’s most famous writers, such as Synge, Yeats himself and George Bernard Shaw. The Gate was founded in 1928 to promote European and American Avant Garde works. The Grand Canal Theatre is a new 2,111 capacity theatre which opened in March 2010 in the Grand Canal Dock.

Apart from being the focus of the country’s literature and theatre, Dublin is also the focal point for much of Irish art and the Irish artistic scene. The Book of Kells, a world-famous manuscript produced by Celtic Monks in AD 800 and an example of Insular art, is on display in Trinity College. The Chester Beatty Library houses the famous collection of manuscripts, miniature paintings, prints, drawings, rare books and decorative arts assembled by American mining millionaire (and honorary Irish citizen) Sir Alfred Chester Beatty (1875–1968). The collections date from 2700 BC onwards and are drawn from Asia, the Middle East, North Africa and Europe.

In addition public art galleries are found across the city, including the Irish Museum of Modern Art, the National Gallery, the Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery, the Douglas Hyde Gallery, the Project Arts Centre and the Royal Hibernian Academy. In recent years Dublin has become host to a thriving contemporary art scene. Some of the leading private galleries include Green on Red Gallery, Kerlin Gallery, Kevin Kavangh Gallery and Mother’s Tankstation, each of which focuses on facilitating innovative, challenging and engaging contemporary visual art practice.

Three branches of the National Museum of Ireland are located in Dublin: Archaeology in Kildare Street, Decorative Arts and History in Collins Barracks and Natural History in Merrion Street. The same area is also home to many smaller museums such as Number 29 on Fitzwilliam Street and the Little Museum of Dublin on St. Stephen’s Green. Dublin is home to the National College of Art and Design, which dates from 1746, and Dublin Institute of Design, founded in 1991.

Dublin has long been a city with a strong underground arts scene. Temple Bar was the home of many artists in the 1980s, and spaces such as the Project Arts Centre were hubs for collectives and new exhibitions. The Guardian noted that Dublin’s independent and underground arts flourished during the economic recession of 2010. Dublin also has many acclaimed dramatic, musical and operatic companies, including Festival Productions, Lyric Opera Productions, the Pioneers’ Musical & Dramatic Society, the Glasnevin Musical Society, Second Age Theatre Company, Opera Theatre Company and Opera Ireland. Ireland is well known for its love of baroque music, which is highly acclaimed at Trinity College.

Dublin was shortlisted to be World Design Capital 2014. Taoiseach Enda Kenny was quoted to say that Dublin “would be an ideal candidate to host the World Design Capital in 2014”.

Entertainment

Dublin has a vibrant nightlife and is reputedly one of Europe’s most youthful cities, with an estimate of 50% of citizens being younger than 25. There are many pubs across the city centre, with the area around St. Stephen’s Green and Grafton Street, especially Harcourt Street, Camden Street, Wexford Street and Leeson Street, having the most popular nightclubs and pubs.

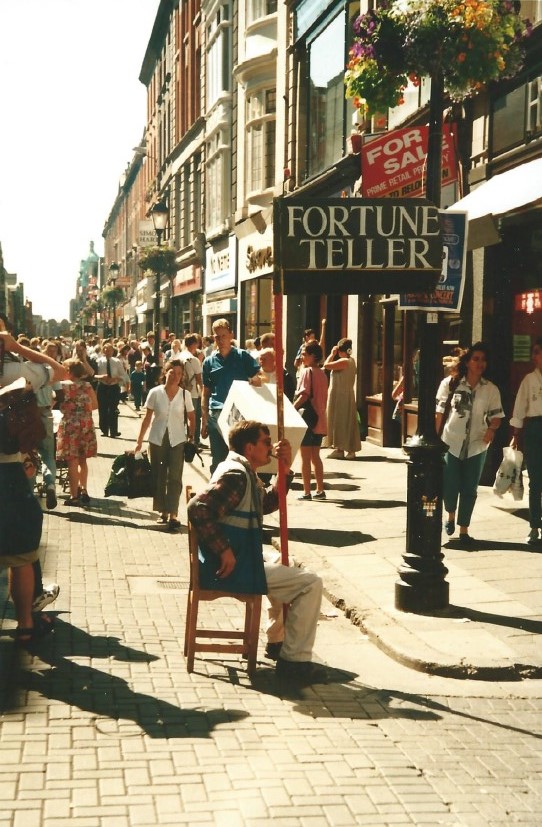

The best known area for nightlife is Temple Bar, south of the River Liffey. The area has become popular among tourists, including stag and hen parties from Britain. It was developed as Dublin’s cultural quarter and does retain this spirit as a centre for small arts productions, photographic and artists’ studios, and in the form of street performers and small music venues. However, it has been criticised as overpriced, false and dirty by Lonely Planet. In 2014, Temple Bar was listed by the Huffington Post as one of the ten most disappointing destinations in the world. The areas around Leeson Street, Harcourt Street, South William Street and Camden/George’s Street are popular nightlife spots for locals.

Live music is popularly played on streets and at venues throughout Dublin in general, and the city has produced several musicians and groups of international success, including U2, one member of Westlife, the Dubliners, the Thrills, Horslips, Jedward, the Boomtown Rats, Boyzone, Ronan Keating, Thin Lizzy, Paddy Casey, Sinéad O’Connor, the Script and My Bloody Valentine. The two best known cinemas in the city centre are the Savoy Cinema and the Cineworld Cinema, both north of the Liffey. Alternative and special-interest cinema can be found in the Irish Film Institute in Temple Bar, in the Screen Cinema on d’Olier Street and in the Lighthouse Cinema in Smithfield. Large modern multiscreen cinemas are located across suburban Dublin. The O2 venue in the Dublin Docklands has played host to many world renowned performers.

Shopping

Dublin is a popular shopping destination for both locals and tourists. The city has numerous shopping districts, particularly around Grafton Street and Henry Street. The city centre is also the location of large department stores, most notably Arnotts, Brown Thomas and Clerys.

The city retains a thriving market culture, despite new shopping developments and the loss of some traditional market sites. Amongst several historic locations, Moore Street remains one of the city’s oldest trading districts. There has also been a significant growth in local farmers’ markets and other markets. In 2007, Dublin Food Co-op relocated to a larger warehouse in The Liberties area, where it is home to many market and community events. Suburban Dublin has several modern retail centres, including Dundrum Town Centre, Blanchardstown Centre, the Square in Tallaght, Liffey Valley Shopping Centre in Clondalkin, Omni Shopping Centre in Santry, Nutgrove Shopping Centre in Rathfarnham, and Pavilions Shopping Centre in Swords.

Irish language

There are 10,469 students in the Dublin region attending the 31 gaelscoileanna (Irish-language primary schools) and 8 gaelcholáistí (Irish-language secondary schools). Dublin has the highest number of Irish-medium schools in the country. There may be also up to another 10,000 Gaeltacht speakers living in Dublin. Two Irish language radio stations Raidió Na Life and RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta both have studios in the city, and the online and DAB station Raidió Rí-Rá broadcasts from studios in the city. Many other radio stations in the city broadcast at least an hour of Irish language programming per week. Many Irish language agencies are also located in the capital. Conradh na Gaeilge offers language classes, has a book shop and is a regular meeting place for different groups. The closest Gaeltacht to Dublin is the County Meath Gaeltacht of Ráth Cairn and Baile Ghib which is 55 km (34 mi) away.

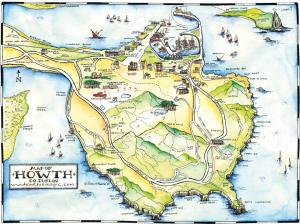

Howth

Howth (/ˈhoʊθ/; Irish: Binn Éadair, meaning “Éadar’s peak”) is a village and outer suburb of Dublin, Ireland. The district occupies the greater part of the peninsula of Howth Head, forming the northern boundary of Dublin Bay. Originally just a small fishing village, Howth with its surrounding once-rural district is now a busy suburb of Dublin, with a mix of dense residential development and wild hillside. The only neighbouring district on land is Sutton. Howth is also home to one of the oldest occupied buildings in Ireland, Howth Castle.

Howth has been a filming location for movies such as The Last of the High Kings and Boy Eats Girl.

Location and access

Howth is located on the peninsula of Howth Head, which begins around 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) east-north-east of Dublin, on the north side of Dublin Bay. The village itself is located 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) from Dublin city centre (the ninth of a series of eighteenth century milestones from the Dublin General Post Office (GPO) is in the village itself), and spans most of the northern part of Howth Head, which is connected to the rest of Dublin via a narrow strip of land (or tombolo) at Sutton Cross.

Howth is at the end of a regional road from Dublin and is one of the two northern termini of the DART suburban rail system. It is served by Dublin Bus.

History and etymology

The name Howth is thought to be of Norse origin, perhaps being derived from the Old Norse Hǫfuð (“head” in English). Norse vikings colonised the eastern shores of Ireland and built the settlement of Dublin as a strategic base between Scandinavia and the Mediterranean. Norse Vikings first invaded Howth in 819.

After Brian Ború, the High King of Ireland, defeated the Norse in 1014, many Norse fled to Howth to regroup and remained a force until their final defeat in Fingal in the middle of the 11th century. Howth still remained under the control of Irish and localized Norse forces until the invasion of Ireland by the Anglo-Normans in 1169.

Without the support of either the Irish or Scandinavian powers, Howth was isolated and fell to the Normans in 1177. One of the winning Normans, Armoricus (or Almeric) Tristam, was granted much of the land between the village and Sutton. Tristam took on the name of the saint on whose feast day the battle was won – St Lawrence. He built his first castle near the harbour and the St. Lawrence link remains even today, see Earl of Howth. The original title of Baron of Howth was granted to Almeric St. Lawrence by Henry II of England in 1181, for one Knight’s fee.

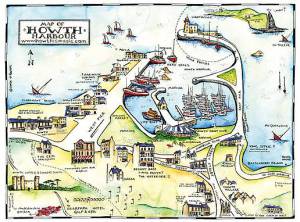

Howth was a trading port from at least the 14th century, with both health and duty collection officials supervising from Dublin, although the harbour was not built until the early 19th century.

A popular tale concerns the pirate Gráinne O’Malley, who was rebuffed in 1576 while attempting a courtesy visit to Howth Castle, home of the Earl of Howth. In retaliation, she abducted the Earl’s grandson and heir, and as ransom she exacted a promise that unanticipated guests would never be turned away again. She also made the Earl promise that the gates of Deer Park (the Earl’s demesne) would never be closed to the public again, and the gates are still open to this day, and reputedly, a place is set at table for unexpected guests.

In the early 19th century, Howth was chosen as the location for the harbour for the mail packet (postal service) ship. One of the arguments used against Howth by the advocates of Dún Laoghaire was that coaches might be raided in the badlands of Sutton! (at the time Sutton was open countryside.)[1] However, due to silting, the harbour needed frequent dredging to accommodate the packet and eventually the service was relocated to Dún Laoghaire. George IV visited the harbour in August 1821.

On the 26 July 1914, 900 rifles were landed at Howth by Robert Erskine Childers for the Irish Volunteers. Many were used against the British in the Easter Rising and in the subsequent Anglo-Irish War.

The harbour was radically rebuilt in the late 20th century, with distinct fishing and leisure areas formed, and the installation of a modern ice-making facility. A new lifeboat house was later constructed, and Howth is today home to both the RNLI (lifeboat service) and the Irish Coastguard.

Features

Howth Head is one of the dominant features of Dublin Bay, with a number of peaks, the highest of which is Black Linn. In one area, near Shielmartin, there is a small peat bog, the Bog of the Frogs. The wilder parts of Howth can be accessed by a network of paths (many are rights of way) and much of the centre and east is protected as part of a Special Area of Conservation of 2.3 square kilometres (570 acres).

The peninsula has a number of small, fast-running streams, three of which run through the village, with more, including the Bloody Stream, in the adjacent Howth Demesne. The streams passing through the village are, from east to west, Coulcour Brook, Gray’s Brook or the Boggeen Stream, and Offington Stream.

The island of Ireland’s Eye, part of the Special Area of Conservation, lies about a kilometre north of Howth harbour, with Lambay Island some 5 km further to the north. A Martello tower exists on each of these islands with another tower overlooking Howth harbour (opened as a visitor centre and Ye Olde Hurdy-Gurdy Museum of Vintage Radio on June 8, 2001) and another tower at Red Rock, Sutton. These are part of a series of towers built around the coast of Ireland during the 19th century.

Built heritage

Howth Castle, and its estate, Deer Park, are key features of the area.

On the grounds of Howth Castle lies a collapsed Dolmen known locally as Aideen’s Grave.

At the south-east corner of Howth Head, in the area known as Bail(e)y (historically, the Green Bayley) is the automated Baily Lighthouse, successor to previous safety mechanisms, at least as far back as the late 17th century.

In Howth village is St. Mary’s Church and graveyard. The earliest church was built by Sitric, King of Dublin, in 1042. It was replaced around 1235 by a parish church, and then, in the second, half of the 14th century, the present church was built. The building was modified in the 15th and 16th centuries, when the gables were raised, a bell-cote was built and a new porch and south door were added. The St. Lawrences of nearby Howth Castle also modified the east end to act as a private chapel; inside is the tomb of Christopher St Lawrence, 2nd Baron Howth, who died in 1462, and his wife, Anna Plunkett of Ratoath.

Also of historic interest is The College, on Howth’s Main Street.

Trinity College, Dublin

Trinity College (Irish: Coláiste na Tríonóide), formally known as the College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity of Queen Elizabeth near Dublin, is the sole constituent college of the University of Dublin in Ireland. The college was founded in 1592 as the “mother” of a new university, modelled after the collegiate universities of Oxford and of Cambridge, but, unlike these, only one college was ever established; as such, the designations “Trinity College” and “University of Dublin” are usually synonymous for practical purposes. It is one of the seven ancient universities of Britain and Ireland, as well as Ireland’s oldest university.

Originally established outside the city walls of Dublin in the buildings of the dissolved Augustinian Priory of All Hallows, Trinity College was set up in part to consolidate the rule of the Tudor monarchy in Ireland, and it was seen as the university of the Protestant Ascendancy for much of its history.

Although Catholics and Dissenters had been permitted to enter as early as 1793, certain restrictions on their membership of the college remained until 1873 (professorships, fellowships and scholarships were reserved for Protestants), and the Catholic Church in Ireland forbade its adherents, without permission from their bishop, from attending until 1970. Women were first admitted to the college as full members in 1904.

Trinity College is now surrounded by Dublin and is located on College Green, opposite the former Irish Houses of Parliament. The college proper occupies 190,000 m2 (47 acres), with many of its buildings ranged around large quadrangles (known as ‘squares’) and two playing fields. Academically, it is divided into three faculties comprising 25 schools, offering degree and diploma courses at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels. In 2011, it was ranked by the Times Higher Education World University Rankings as the 110th best university in the world, by the QS World University Rankings as the 65th best, by the Academic Ranking of World Universities as within the 201–300 range, and by all three as the best university in Ireland.

The Library of Trinity College is a legal deposit library for Ireland and the United Kingdom, containing over 4.5 million printed volumes and significant quantities of manuscripts (including the Book of Kells), maps and music.

Early history

The first University of Dublin (known as the Medieval University of Dublin and unrelated to the current university) was created by the Pope in 1311, and had a Chancellor, lecturers and students (granted protection by the Crown) over many years, before coming to an end at the Reformation.

Following this, and some debate about a new university at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, in 1592 a small group of Dublin citizens obtained a charter by way of letters patent from Queen Elizabeth incorporating Trinity College at the former site of All Hallows monastery, to the south east of the city walls, provided by the Corporation of Dublin. The first Provost of the College was the Archbishop of Dublin, Adam Loftus (after whose former college at Cambridge the institution was named), and he was provided with two initial Fellows, James Hamilton and James Fullerton. Two years after foundation, a few Fellows and students began to work in the new College, which then lay around one small square.

During the following fifty years the community increased and endowments, including considerable landed estates, were secured, new fellowships were founded, the books which formed the foundation of the great library were acquired, a curriculum was devised and statutes were framed. The founding Letters Patent were amended by succeeding monarchs on a number of occasions, such as by James I (1613) and most notably by Charles I (who established the Board – then the Provost and seven senior Fellows – and reduced the panel of Visitors in size) and supplemented as late as the reign of Queen Victoria (and later still amended by the Oireachtas in 2000).

18th and 19th centuries

The eighteenth century was for the most part peaceful in Ireland, and Trinity College shared in this calm, though at the beginning of the period a few Jacobites and at its end some political radicals perturbed the College authorities. During this century Trinity College was seen as the university of the Protestant Ascendancy. Parliament, meeting on the other side of College Green, made generous grants for building. The first building of this period was the Old Library building, begun in 1712, followed by the Printing House and the Dining Hall. During the second half of the century Parliament Square slowly emerged. The great building drive was completed in the early nineteenth century by Botany Bay, the square which derives its name in part from the herb garden it once contained (and which was succeeded by Trinity College’s own Botanic Gardens). Following early steps in Catholic Emancipation, Catholics were first allowed to apply for admission in 1793, prior to the equivalent change at the University of Cambridge and the University of Oxford. However, until 1970, soon before the retirement of Archbishop McQuaid, the Irish Catholic bishops implemented a general ban on Catholics entering Trinity College, with few exceptions, because of its largely Anglican ethos.

The nineteenth century was also marked by important developments in the professional schools. The Law School was reorganised after the middle of the century. Medical teaching had been given in the College since 1711, but it was only after the establishment of the school on a firm basis by legislation in 1800, and under the inspiration of one Macartney, that it was in a position to play its full part, with such teachers as Graves and Stokes, in the great age of Dublin medicine. The Engineering School was established in 1842 and was one of the first of its kind in Ireland and Britain.

In December 1845 Denis Caulfield Heron was the subject of a hearing at Trinity College. Heron had previously been examined and, on merit, declared a scholar of the college but had not been allowed to take up his place due to his Catholic religion. Heron appealed to the Courts which issued a writ of mandamus requiring the case to be adjudicated by the Archbishop of Dublin and the Primate of Ireland. The decision of Richard Whately and John George de la Poer Beresford was that Heron would remain excluded from Scholarship. In 1873, all religious tests were abolished, except for entry to the divinity school, and Catholics were accepted as students.

20th century

Women were admitted to Trinity College as full members for the first time in 1904.

In 1907 when the Chief Secretary for Ireland proposed the reconstitution of the University of Dublin. A Dublin University Defence Committee was created and was successful in campaigning against any change to the status quo, while the Catholic bishops’ rejection of the idea ensured its failure among the Catholic population. Chief among the concerns of the bishops was the remains of the Catholic University of Ireland, which would become subsumed into a new university, which on account of Trinity College would be part Anglican. Ultimately this episode led to the creation of the National University of Ireland. In the post independence period Trinity College suffered from a cool relationship with the new state. On 3 May 1955 the Provost, Dr A.J.McConnell pointed out in a piece in the Irish Times that certain state funded County Council scholarships excluded Trinity College from the list of approved institutions, this he suggested amounted to religious discrimination.

The School of Commerce was established in 1925, and the School of Social Studies in 1934. Also in 1934, the first female professor was appointed.

1958 saw the first Catholic to reach the Board of Trinity as a Senior Fellow.

In 1962 the School of Commerce and the School of Social Studies amalgamated to form the School of Business and Social Studies. In 1969 the several schools and departments were grouped into Faculties as follows: Arts (Humanities and Letters); Business, Economic and Social Studies; Engineering and Systems Sciences; Health Sciences (since October 1977 all undergraduate teaching in dental science in the Dublin area has been located in Trinity College); Science.

In 1970 the Catholic Church, through the then Archbishop of Dublin John Charles McQuaid, lifted its policy of disapproval or even excommunication for Catholics who enrolled without special dispensation. At the same time, the Trinity College authorities invited the appointment of a Catholic chaplain to be based in the college. There are now two such Catholic chaplains.

In the late 1960s, there was a proposal for University College, Dublin, of the National University of Ireland to become a constituent college of a newly reconstituted University of Dublin. This plan, suggested by Brian Lenihan and Donogh O’Malley, was dropped after opposition by Trinity College students.

From 1975, the Colleges of Technology that now form the Dublin Institute of Technology had their degrees conferred by the University of Dublin. This arrangement was discontinued in 1998 when the DIT obtained degree-granting powers of its own.

The School of Pharmacy was established in 1977 and around the same time, the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine was transferred to University College, Dublin. Student numbers increased sharply during the 1980s and 1990s, with total enrolment more than doubling, leading to pressure on resources and subsequent investment programme.

1991 saw Thomas Noel Mitchell become the first Roman Catholic elected Provost of Trinity College

21st century

Trinity College is today in the centre of Dublin. At the beginning of the new century, it embarked on a radical overhaul of academic structures to reallocate funds and reduce administration costs, resulting in, for instance, the mentioned reduction from six to just three faculties. The ten-year strategic plan prioritises four research themes with which Trinity College seeks to compete for funding at the global level.